Paul Gardner looks to a time when politics and Masonry were not precluded, but shush! This was London Masons and the Spitalfields Act of 1773-1865

Spitalfields was a hive of activity in the mid-1700s and a mecca for immigrants to live, socialise and find work, usually in weaving and allied trades often through ‘lodges’.

In modern times Freemasons are enjoined to avoid ‘rashness’ and in so doing desist from topics of politics and religion.

But it was never thus so and in this period of interest the Masonic lodge was the hotbed of intrigue and scheming, usually for betterment and work prospects.

It would be fair to say the ‘lodge’ was the centre of later ‘trade union’ activity and almost akin to Livery Companies.

Noteworthy also in the Spitalfields area were many ‘quasi’ Masonic lodges with similar regalia, perhaps better explained as mutual dependency groups, exampled by the Loyal United Friend, a Jewish fraternal organisation which disappeared in the 19th century. As seen by the apron of the Loyal United Friends.

Christ Church, Spitalfields. By Diliff – Own work,

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The area that is now Spitalfields was mainly fields and nursery gardens until late in the 17th century when streets were laid out for Irish and Huguenot silk weavers.

The first known human use of the area is a Roman cemetery which was to the east of the Bishopsgate thoroughfare, which roughly follows the line of Ermine Street: the main highway to the north from Londinium. There was also a sanatorium in the fields (hospital-fields).

In 1729, Spitalfields was detached from the parish of Stepney and organized as a civil parish divided into two ecclesiastical subdivisions, namely; Christ Church Spitalfields and St. Stephen’s Spitalfields.

The church of St. Stephen Spitalfields was built in 1860 by public subscription but was demolished in 1930. The adjacent vicarage is all that remains. Predominant oldest being Christ Church

Spitalfields’ historic association with the silk industry was established by French Protestant (Huguenots) refugees who settled in this area after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

By settling here, outside the bounds of the City of London, they hoped to avoid the restrictive legislation of the City Guilds.

The Huguenots brought with them little, apart from their skills, and an Order in Council of 16 April 1687 raised £200,000 for the relief of their poverty.

In December 1687, the first report of the committee set up to administer the funds reported that 13,050 French refugees were settled in London, primarily around Spitalfields, but also in the nearby settlements of Bethnal Green, Shoreditch, Whitechapel, and Mile End. Many Masonic lodges historically had Huguenots as active members.

Private or ‘St Johns’ lodges as they were commonly known existed, and best exampled by today’s Kent Lodge which almost certainly existed as far back as 1721.

This was the world of Lodge No. 8 which under Dermott’s Antients thrived having rowed in with him in 1752.

Dermott, a painter and immigrant from Dublin, carved his niche in the annuls of masonry and became the Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of the Antients, which he founded.

Thus, it was the Lodge which met at the Ship & Anchor, Quaker Street, Spitalfields who on 13 January 1752 accepted the Antient Constitution and was allotted a warrant No. 9. On 27 December of the same year with the erasure of No. 7, Lodge No. 9 became Lodge No. 8, by closing up.

All warrants were re-issued and signed by Lord Blessington in 1758. It is through the recorded history of No 65 that the lineage of the lodge is traced back to 1721.

England in the 18th century was a land of smuggling; high import taxes on raw and finished silk made the silk trade no exception. The industry was marked by frequent rioting by silk weavers.

In 1719 there was a riot of 4,000 weavers against women wearing Indian cotton calicoes and linens. They would literally attack women wearing the clothing. There were riots each year from 1764-1769.

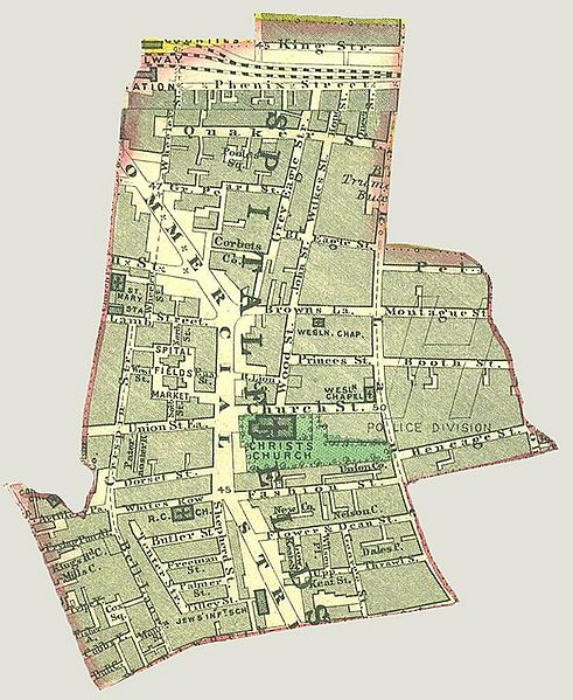

A map of the parish of Spitalfields c.1885,

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Parliament, its members finding themselves and their homes harassed by rioters, passed the Spitalfields Act of 1773, allowing magistrates to set the exact rate that masters could pay journeymen.

The act also made it unprofitable to buy machines or develop new techniques. The economic reality, ironically, was that the industry had for decades benefited from, if not depended on, the preparation of raw silk by machines.

While the act appeared to be a savvy move for a Parliament tired of riots, it didn’t help the industry. The act was ‘exceedingly popular’ until 1785, at which point the substitution of cotton cloth for other fabrics devastated the market for silk.

Pay rates were not reduced accordingly. By 1793, 4,000 looms were idle. A revival in the trade during the Napoleonic Wars was followed by worse conditions starting in 1816. Two-thirds of weavers were out of work.

In 1824, the Spitalfields Act of wage control for silk weavers was repealed after being in force for 50 years.

The act was essentially a disaster that devastated the industry and the workers. The silk industry directly employed an estimated 40,000 looms and their attendant weavers in and around London, many of them in the Spitalfields area.

Indirectly, the industry supported an estimated 400,000 workers and their dependents.

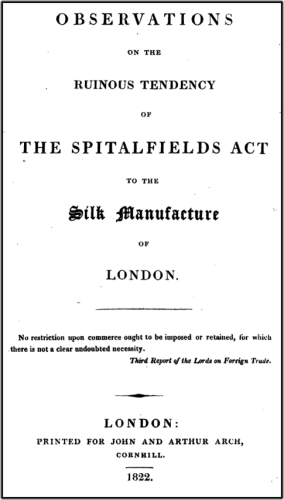

In 1822, a 40-page propaganda pamphlet ‘Observations on the Ruinous Tendency of the Spitalfields Act to the Silk Manufacture of London’ was published, laying out the key points as to why price controls on labour are against the long-term interests of the workingmen and the masters employing them.

Duty-free import of French silk in 1860 killed the domestic silk industry, entirely to the benefit of English consumers.

This did more harm than good as it prevented employers rewarding superior merit and skill. The pamphlet thus argued that repeal of the act would be to the general good of all, masters, and journeymen, in the Spitalfields silk trade; points being:

Damage to Trade:

• Trade has prospered in spite of the act, not because of it. Spitalfields would have prospered more without the act.

• The Spitalfields Act has increased prices, thereby excluding Spitalfields silk products from all foreign markets and much of the home market.

• Silk production has shifted to the country, where it can be done for two-thirds the price. (Similarly, the act encourages smuggling from abroad.)

• Prices must drop to continue production in Spitalfields, and price drops can happen only with “the abrogation of all restrictions on labour, and a more extensive use of machinery.”

• It is in principle well accepted that prices must be subject to supply and demand, if buyers are to find sellers and sellers buyers. Having the magistrates fix all prices for goods and labour is an absurdity.

Damage to the Manufacturer:

• Manufacturers who’ve invested capital in the trade find their investment jeopardized, (as they can’t manufacture at a profit).

• “The price of the article is unnecessarily raised, and its sale in consequence restricted.”

• In practice, magistrates don’t allow wages to decline.

• “All improvements in Machinery, by which the price of goods might be lowered, and the sale extended, are checked and discouraged.”

• Competitors are encouraged outside of Spitalfields, further damaging the investment of Spitalfields manufacturers (and encouraging them to leave). Manufacturers who engage in trade in Spitalfields and the country face fines. In fact, one case of a Spitalfields manufacturer hiring paupers in the country to work for him, when brought to the attention of Spitalfields journeymen, led to him being fined.

Damage to the Journeyman:

• “It tends to diminish the demand for his labour” by setting wage rates too high.

• It is in the long-term interest of manufacturers to have plenty of workers, and for those workers to have plenty of jobs. Therefore, manufacturers will not want to set wages so low as to discourage workers from the trade.

• Both the labourer and manufacturer have the same long-term interest in flourishing of the industry.

• The profit of the manufacturer is the only source of payment to labour. Labour therefore needs profitable manufacturers to work for.

• The labourer’s most important property is his labour; it is therefore essential he have a steady demand for it.

• “It banishes the trade from Spitalfields … [and] threatens total destruction to the journeymen.” The trade is moving to the unregulated countryside, which is seeing a huge boom in employment. There will eventually be no more weaver jobs in Spitalfields.

• “It defrauds him of his due when the trade happens to prosper.” It is only just that he share in such prosperity, but under the act, the worker cannot be paid higher wages during good times.

• “Instead of making good to him in slack times the loss he suffered when the trade flourished, the Act throws him out of work altogether.”

Because the worker is completely unemployed during bad times, the burden of those times falls completely on him. Whereas if he had work at lower wages, the burden would be lessened:

• It is therefore false that the act “prevents the growth of pauperism, by insuring to the weaver a fair price for his labour.” “Free labour” protects against pauperism.

• “We assert, without fear of contradiction, that to force up the price of labour, whether the manufactured article will bear it or not, is to depress the trade, injure the labourer, and by rendering employment uncertain, to increase the demand on the parish fund, and destroy, instead of building up, the little ‘hedge of a man’s independence.'”

• There is no evidence that “the Act has prevented those riotous and tumultuous assemblages which once took place in Spitalfields, and disposes the people to peace and submission.” There has been plenty of distress, which the law did nothing to prevent, yet the people did not riot. The changed character of the people is the cause of the change.

• The “workman’s security” is that the manufacturer needs labourers in order to keep his capital profitably employed; he will therefore gladly pay them so long as he can make money.

• Free labour would lead to competition for such skilled workers. During bad times they would be better off under free labour, as they would at least have work. This creates the additional outcomes that workers will be thrifty, become good workmen, and find other employment; the bad times will be shorter, and workmen will still retain some wages during them.

Bold defiance from a ‘Trade Organisation’ (Trade Unionism); the argument being that workers and manufacturers alike will benefit from free labour and free prices is conscionable. However, the principle of supply and demand is well established as the basis for setting prices.

Obviously, an industry will not exist unless people are willing to buy its products, and people will not buy a more expensive product when they can buy the same thing less expensively.

Therefore, the industry in Spitalfields needed to be legally permitted to sell its products at the market rates.

The act did not permit the industry in Spitalfields to sell its product at market rates, because it locked the prices of the silk goods and labour bought from the journeymen.

It was supposed to protect the wages of the workers. However, it does not protect the wages, because all wages come from the sales of goods; and the act cannot force anyone to buy the product of labour when a less-expensive alternative is available from home or abroad.

Attempts to keep out foreign imports simply led to smuggling, and the industry sprang up in the English countryside where wage regulations were not in force.

Free labour and the introduction of machinery, on the other hand, allow manufacturers to expand and provide regular work for labourers during bad times and allow for the competition that will drive up wages during good times.

For the workers and manufacturers to flourish in Spitalfields, price controls for wages and goods had to be removed.

The 1822 ‘Observations on the Ruinous Tendency of the Spitalfields Act to the Silk Manufacture of London’ is a great example of the economic arguments against price controls.

The Act was a price control on the amounts master weavers in London and other silk centres could pay journeymen for each piece of silk.

This not only removed all incentive to pay higher wages during good times, it made it illegal to do so.

During bad times many workers had no work. This is because master weavers had to cut the prices, they sold their goods for, but they could not cut the prices they paid for labour and what they ultimately paid for goods.

Therefore, the master weavers simply shut down operations. By 1832, Spitalfields became a run-down slum and continued to be one of the most crime-ridden areas in London throughout the century.

This minute identifies that Kent Lodge, still located at Spitalfields, maintained its connection with the weaving industry and was considered of sufficient importance to be asked to intervene in an industrial dispute.

The other implication has a more far-reaching effect. The decline of the silk-weaving industry and the eventual absorption of the individuality of Spitalfields in the spreading mass of London’s East End during the nineteenth century resulted in a Masonic Lodge retaining its location without its original raison d’etre.

The industry epithet ‘London Luddites’ could thereafter be expunged!

His Royal Highness Augustus Frederick Duke of Sussex (1773-1843)

IMAGE LINKED: New York Public Library Digital Collections (CC BY 4.0)

Royal Kent Lodge No.15 states:

16th June, 1823. Bro. Collcott, Hon. Secy., informed the Lodge that he had been waited on by one of the Committee of Journeymen Weavers for our Lodge to endeavour to gain an interview with H.R.H. the Duke of Sussex, our Most Worship’ll Grand Master, to support their Petition in the House of Lords against the Bill now pending in Parliament to repeal the ‘Spitalfields Act’ which his Royall High’ss most graciously consented to, when our Rt. Wor’ll Br. Mahon, P.S.G.W., presented the Deputation to His Royal Highness, which was kindly received and very favourably answered, whereupon Br. Temple prop’d that the expenses of the day of attendance (Two Guineas) be paid by the Lodge.

Kent Lodge (since 2016 readopting its early name, granted by The Duke of Kent, of Royal Kent Lodge) can be very proud that it remains a matter of historical record that members of this Masonic Lodge meeting at the Ship and Anchor in Spitalfields through their involvement in their locality helped to repealing an Act of social injustice of some 50 years standing.

Further Reading

The Huguenots and Early Modern Freemasonry

The Huguenots influence in the development of early modern Freemasonry at the time of the formation of the Grand Lodge in London around 1717 / 1723.

more….

Article by: Paul Gardner

Paul was Initiated into the Vale of Beck Lodge No 6283 (UGLE) in the Province of West Kent, England serving virtually continuously in Office and occupying the WM Chair on three occasions.

Paul joined Stability Lodge No 217 in 1997 (UGLE) and now resides with Kent Lodge No 15, (UGLE) the oldest Atholl Lodge with continuous working since 1752, where he was Secretary and now Assistant Secretary and archivist, having been WM in 2002.

In Holy Royal Arch he is active in No 15 Chapter and Treasurer of No 1601, which was the first UGLE Universities Scheme Chapter in 2015.

He was Secretary of the Association of Atholl Lodges which maintains the heritage of the remaining 124 lodges holding ‘Antients’ Warrants and has written a book on Laurence Dermott. - https://antients.org

Recent Articles: by Paul Gardner

Unearth the mystic origins of Freemasonry in 'That He May Be Crafted.' Paul Gardner explores the symbolic use of working tools from the earliest days of this secret society, revealing a time when only two degrees existed. Delve into this fascinating study of historical rituals and their modern relevance. |

Paul Gardner looks to a time when politics and Masonry were not precluded, but shush! This was London Masons and the Spitalfields Act of 1773-1865. |

That rank is but the guinea’s stamp, the man himself’s the gold. But what does this mean, even given the lyric and tone of Burns’ time? It is oft times used in a derogatory sense, (somewhat in good humour) between Masons (or not) on the achieving of honours. But its antecedents are much more complex than that. |

John and Timothy Coleman Blanchflower were initiated in Walpole Lodge, No. 1500, Norwich England on 2 December 1875; noted as a purveyor of ‘sauce’ to masons! |

Jacob’s Ladder occupies a conspicuous place among the symbols of Freemasonry being on the First Degree Tracing Board, the most conspicuous and first seen by the candidate on his initiation – a vision of beauty and intrigue for the newly admitted. |

During a detective hunt for the owner of a Masonic jewel, Paul Gardner discovered the extraordinary life of a true eccentric: Dr William Price, a Son of Wales, and a pioneer of cremation in Great Britain. Article by Paul Gardner |

Paul Gardner tells the story of his transition from one rule book to another – from the Book of Constitutions to the Rule Book for Snooker! |

Due or Ample Form? What is ‘Ample’ form, when in lodges the term ‘Due’ form is used? |

The Butcher, the Baker, the Candlestick Maker Paul Gardner explores the Masonic link between provincial towns’ craftsmen, shop keepers and traders in times past. Many remain in the modern era and are still to be found on the high street. |

Masonic dining and banquets, at least for the annual Investitures, were lavish, and Kent Lodge No. 15, the oldest Atholl lodge with continuous working from 1752, was no exception. |

The ‘cable-tow’ or ‘noose’ is used in Craft Masonry as part of the ritual, as are ropes and ties in other degrees - but what does it symbolise? |

Paul Gardner reflects on those days of yore and the “gentleman footballer” in Masonry |

What is the Masonic connection with the 1914 Christmas Mary Tin |

That Takes the Biscuit - The Patriot Garibaldi Giuseppe Garibaldi Italian general and politician Freemason and the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy. |

W.Bro. Paul Gardner looks at a mid 19th century artefact and ponders ‘Chairing’ |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device