The Mysterious Eighteenth-Century Graffiti at James Gibbs’ St. Mary-Le-Strand Church: Stonemasons’ or Freemason’s Legacy? [1]

James Gibbs & St. Mary-Le-Strand Church

Located today at the top of an internal staircase at St Mary-Le-Strand Church in the heart of the Strand-Aldwych District, are a series of mysterious carvings etched into the wall near the Muniments Room.

These carvings are in such a position that they are easy to miss, given their location in a non-public area.

It was a common occurrence in churches from the Middle Ages for stonemasons to carve their individual marks on a building, as the majority of masons were illiterate and mason’s marks allowed each mason to receive the correct pay as their individual mark would have been recognised by the paymaster.

This essay will examine several of these marks and try to determine whether they are simply graffiti left in place by stonemasons as a means of identification, or whether they have a deeper, more esoteric meaning in relation to Freemasonry.

However, being a stonemason and also being a Freemason were entirely compatible during this period as Freemasonry developed out of the stonemason’s craft and beliefs. [2]

Entrance to St. Mary-Le-Strand.

IMAGE CREDIT: author

James Gibbs and The Commission for Building Fifty New Churches

St Mary-Le-Strand Church was built by the Scottish architect James Gibbs (1682-1754) from 1714 and consecrated on 1st January 1724.

St Mary-Le-Strand was the first of twelve churches (collectively known as the Queen Anne Churches) Commission for Building Fifty New Churches Gibbs was employed with Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736) [3] in the role of Surveyor to the New Churches Commission.

It had long been recognised that there were not enough places of worship to serve a growing London congregation.

Unfortunately for James Gibbs, a Catholic with known Jacobite sympathies [4], he was dismissed from his post by November 1715 due to his political beliefs and religion.

This coincided with the death of Queen Anne in 1714 and immediately followed by the abortive Jacobite restitution attempt of 1715, led by John Erskine, Earl of Mar (1675-1732), one of James Gibbs’ closest associates and a known friend. [5]

A fellow Scottish architect and rival, Colin Campbell (1676-1729), had also written to the New Churches Commission informing them that Gibbs was a known Catholic and a dissident and by implication asking for his dismissal (no doubt for Campbell to try and take over Gibbs’ architectural commissions). [6]

Portrait of James Gibbs

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Gibbs, rightly upset, wrote back to the Commission in his defence, informing them that the report was ‘entirely false and scandalous’. [7]

Gibbs had expediently also recently converted to Anglicanism. Unfortunately for Gibbs, this defence fell on deaf ears at a time when the newly installed Hanoverian regime of Protestant claimants had just inherited the Crown and the political situation was noticeably unstable.

The Tory party had been dismissed from government and the pro-Hanoverian Whig party were now in power and in their ascendancy. [8]

However, Gibbs was halfway through building the church, and offered to complete its building for free and this was accepted. [9]

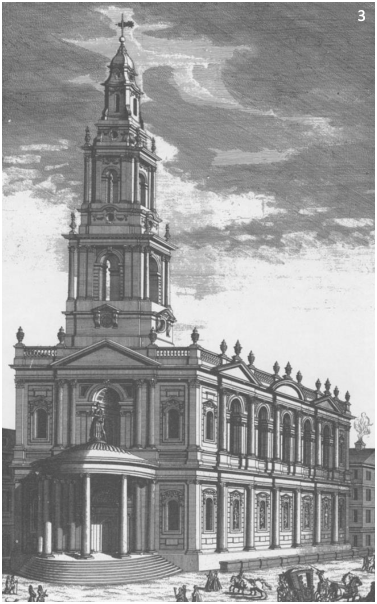

St. Mary-Le-Strand Church is, perhaps Gibbs’ most noticeably Baroque building, commissioned just six years after he had returned from Italy in 1708 where he had spent over three years studying architecture under architect Master Carlo Fontana (1634/1638-1714).

After the completion of St. Mary-Le-Strand, Gibbs felt it expedient to modify his architectural style by limiting its Italianate Baroque excesses in order to fall in with Neo-Palladianism which was beginning to assert itself as the dominant national style for Georgian England under the direction of Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1994-1753) and his circle. [10]

Gibbs was employed at Lord Burlington’s mansion at Piccadilly and in the gardens of his villa at Chiswick, until dismissed by the earl around 1717 and replaced by Colen Campbell. [11]

St Mary-Le-Strand from Gibbs’ Book of Architecture’ (1728).

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Although many of Gibbs’ clients were Tories, he fostered relationships with several Whigs such as John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll (1680-1743), for whom Gibbs designed Sudbrook Hall in Petersham and dedicated his Books of Architecture (1728) [12] as he needed Whig commissions and did not want to alienate a lucrative patron base.

Despite his known Jacobite sympathies, Gibbs managed to secure several important commissioned from prominent Whigs and Hanoverian loyalists, including the creation of a Baroque octagonal hall for James Johnston’s house at Twickenham which was built as a homage to the Hanoverian king, his wife and children.

His most influential and well-known work remains his Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields which became a prototype for many churches around the world.

The new St Mary-Le-Strand Church

Little is known about the stonemasons who worked on St Mary-Le-Strand Church. [13]

The church was built on a former site of a famous maypole and Gibbs had originally planned to have a statue of Queen Anne installed.

With her death in 1714 the plan was abandoned, and Gibbs told to modify his original design for the church and to include a spire.

During the course of building the Commissioners were also concerned about the number of costly decorations being applied to the interior of the church.

Despite being dismissed from his role of Surveyor to the New Church Commissioners, Gibbs finished the church which was completed in 1724.

The Graffiti

At the top of the spiral staircase near the Muniments Room are several areas of graffiti, all in close location to each other. Some of the graffiti are just initials and numbers, whilst other graffiti are shapes with decipherable dates. The carvings all appear to be eighteenth-century and have been painted over several times, but the graffiti is clear and legible.

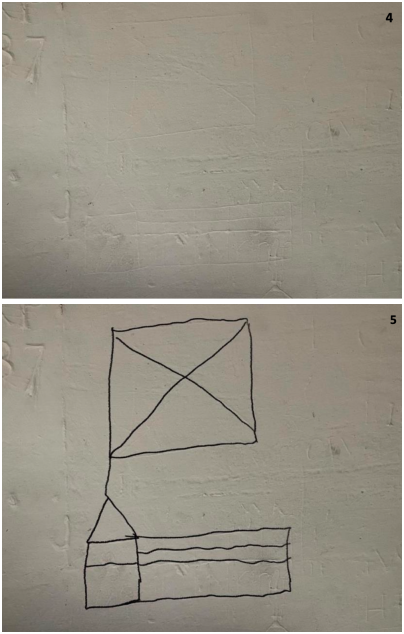

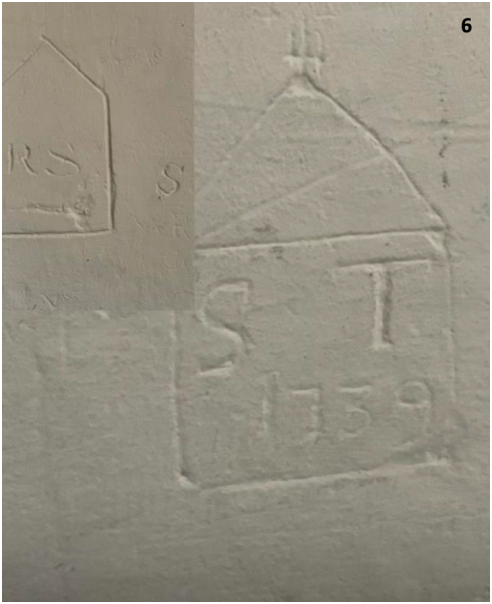

Church and Flag

Graffiti showing graffiti of church and flag/cube and pyramid

IMAGE CREDIT: author

One of the largest pieces of graffiti takes the form of a large rectangle supporting a smaller triangle on its left side.

On closer examination a large flag, almost the same size of the rectangle, can be seen attached via a pole to the tower.

Taken as one carving, the graffiti appears to be a church with an attached tower. Fixed to the tower, the flag takes the form of a saltire cross which can be interpreted as the Cross of St Andrew present on the Scottish flag.

Dates near the carving would give a contemporary dating of around 1739. It is unknown whether Scottish masons were used in the construction of the church, but the carving does indicate the potentiality that at least some stonemasons were Scottish at some point in the church’s building history or that they knew that a fellow Scot had built the church. [14]

Cube, Date and Pyramid

Graffiti showing cube and pyramid, with date

IMAGE CREDIT: author

In the same location as the carving of the church and flag are several other areas of graffiti featuring cubic structures supporting pyramids. One of these carvings contains the initials S T accompanied with the date 1739.

Given its proximity to the church carving this may also be a representation of a church with a spire (if indeed this is part of the same carving).

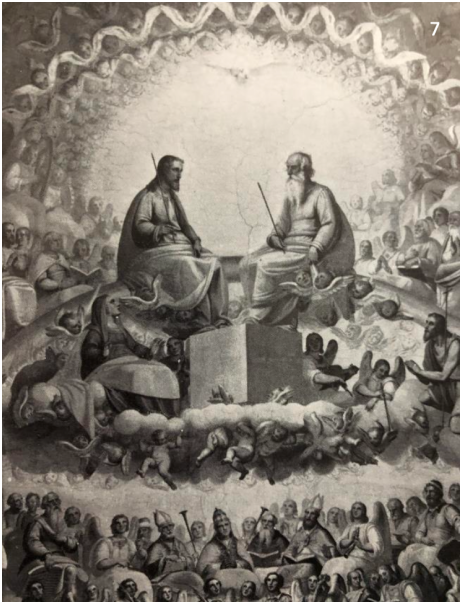

In religious symbolism the cube was viewed as a symbol of perfection as all sides and angles were equal.

Both Moses’s Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple also contained a ‘Holy of Holies’- a room which was a perfect cube, thus as God was believed to have designed his own Temple, the cube was viewed a symbol of the Divine Creator. [15]

Luca Cambiaso (1527-1585): detail of fresco on vault over upper choir of Escorial showing God the father and son seated on a cube.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

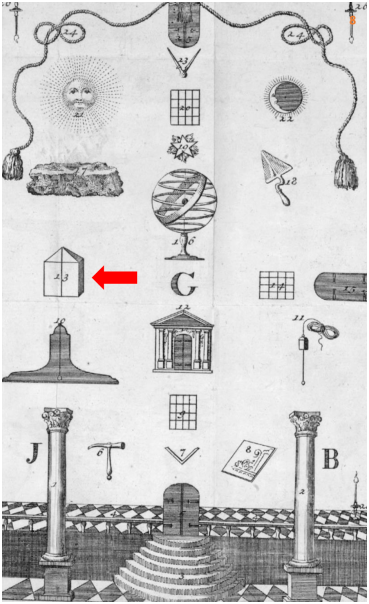

Freemasonry and the Rough and Perfect Ashlar block

Floor-drawing, “Apprentice-Fellow’s Lodge,” L’Ordre des Francs- Maçons Trahi, 1745.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The official Whig orientated history of Freemasonry can be dated to 24th June 1717 when four London lodges joined together to create the ‘Premier Grand Lodge of England’. [16]

However, the roots of Freemasonry were much older with Elias Ashmole (1617- 92) being the oldest known recorded Freemason, his initiation taking place in the mid seventeenth century. [17]

Freemasonry is known for its plethora of Masonic symbolism, used to illustrate its teachings and to convey moralistic instructions among its members.

At its heart, the purpose of Freemasonry was to make the mason a better and more productive member of society.

At the beginning of his Masonic journey, the rough ashlar cube was employed to illustrate the individual in an uneducated state in need of instruction, spiritual purification and education.

Through the teaching of Freemasonry and initiation through its three Craft degrees, [18] the mason would loose his rough edges before becoming the ‘smooth and perfect ashlar’, symbolically then able to take his place as part of the Temple of Humanity.

In France this perfectly cubic smooth ashlar block was often topped with a small triangle leading to a point.

An alternative explanation is that the cube is symbolic of a wool apron worn by a Freemason with its flap turned outward instead of inwards. [19]

A second cubic carving at St Mary-Le-Strand has the initials R S but is not dated.

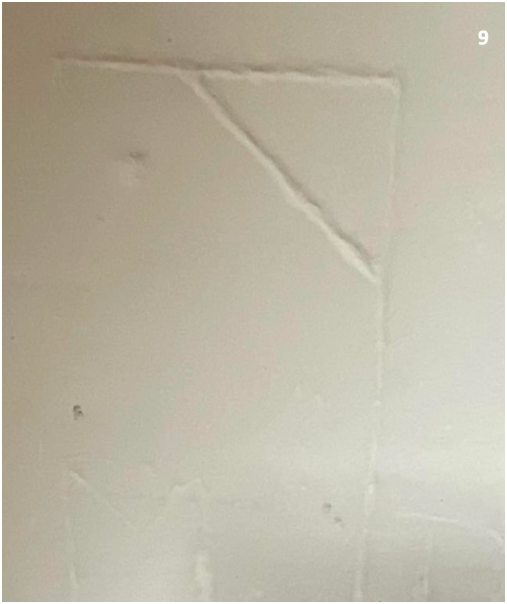

The Gallows Square

Graffiti showing gallows square and letters beneath

IMAGE CREDIT: author

One of the most mysterious and interesting pieces of graffiti to appear on the wall of St Mary-Le-Strand is a carving of what appears to be a set-square or gallows square.

This comprises of two arms of unequal lengths which meet at a 90-degree angle. A third length joins them at approximately 45 degrees to form a small triangle.

The meaning of this piece of graffiti is debatable but interpreted in terms of Masonic symbolism (and in relation to the nearby cubic blocks) it has a discernible Masonic meaning.

In his book Symbolism in Craft Freemasonry, [20] author Colin Dyer goes to some length to explain the meaning of the gallows square, and it is worth quoting here in its entirety:

One of the most interesting suggestions for the original use of the letter G in a Masonic connection arises in connection with the shape of the square…

There seems to be a good deal of opinion which say the shape with arms of uneven length was used in early masonry, whilst there is no doubt that what is known as a ‘gallows’ square was at one time in popular use.

J. S. M. Ward in An Interpretation of Our Masonic Symbols, points out that this shape for the square is precisely the shape of the Greek letter Gamma, equivalent to G in the Roman alphabet, and, further, that in ecclesiastical script used in medieval Europe, this very gallows square shape was used to represent the letter G…

Ward also agrees with the opinion of Sir John Cockburn that the Square and the letter G in early lodges were depicted by the same shape.

Cockburn is quoted as saying that it was the letter G which the early masons wished to depict, symbolising God, and so they used this gallows square shape to represent that letter.

It could just as easily have been that the early Masons wished to show the Square as the major moral instrument of the Craft and then found that it would also represent the G for Geometry.

Whichever is the right way round, there could well be some justification for Ward’s assertion that if a Lodge is to be absolutely correctly furnished according to the original tradition, that the symbol in the centre of the lodge, whether hung from the ceiling or placed on the pentangle on the floor, should take the form of a gallows square. [21]

For whatever reason, the gallows square at Mary-Le-Strand appears reversed.

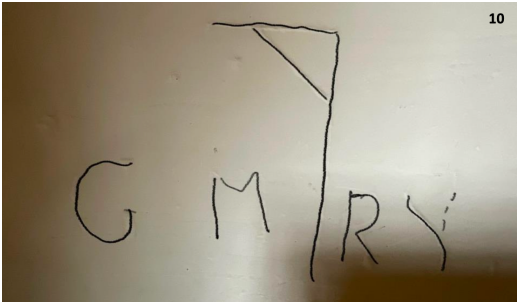

Graffiti possibly spelling out the word ‘Geometry’.

IMAGE CREDIT: author

Immediately beneath the gallows square graffiti at St Mary-Le-Strand Church are the letters GMRY. For some it may be seen as stretching credibility, but is it possible these letters form part of the word ‘Geometry’ which would certainly reinforce the Masonic meaning of the gallows square? [22]

Detail of a painting by William Kent (1685-1748) called Architecture admiring a portrait of Inigo Jones (1573-1652) This shows a man in Oriental attire carrying an oversize set square. The figure may be Hiram Abiff, biblical builder of Solomon’s Temple and a central figure in Masonic lore. Presented by Lord Burlington to his physician, Fellow of the Royal Society and Freemason, Dr Richard Mead (1673-1754).

IMAGE CREDIT: Today on display in the Red Velvet Room at Chiswick House (©️English Heritage).

The gallows square appear elsewhere in early 18th century masonry and also connected to letters, passwords and modes of recognition.

In a Letter from the Grand Mistress of the female free-masons (1762), the poet and satirist Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) wrote the following:

Now, as to the secret Words and Signals used among Free Masons, it is to be observed, that in the Hebrew Alphabet, (as our Guardian hath informed our Lodge in Writing) there are four Pair of Letters, of which each Pair is so like that at first View, they seem to be the same, Beth and Caph, Gimel and Nun, Chethan and Thau, Daleth and Resch, and on these depend all their Signals and Grips.

CHETH and Thau are shaped like two standing Gallowses of two Legs each; when two Masons accost each other, the one cries Cheth and the other answers Thau, signifying that they would sooner be hanged on the Gallows, than divulge the Secret.

Then again Beth and Caph are each like a Gallows lying on one of the Side- Posts, and when used as above, imply this pious Prayer:

May all who reveal the Secret, bang upon the Gallows’ till it falls down.

This is their Master Secret, generally called the Great Word. DALETH and Resch are like two Half Gallowses, or a Gallows cut in two, at the cross Stick on Top, by which when pronounced, they intimate to each other, that they would rather be half- hanged, than name either Word or Signal, before any but a Brother, so as to be understood. [23]

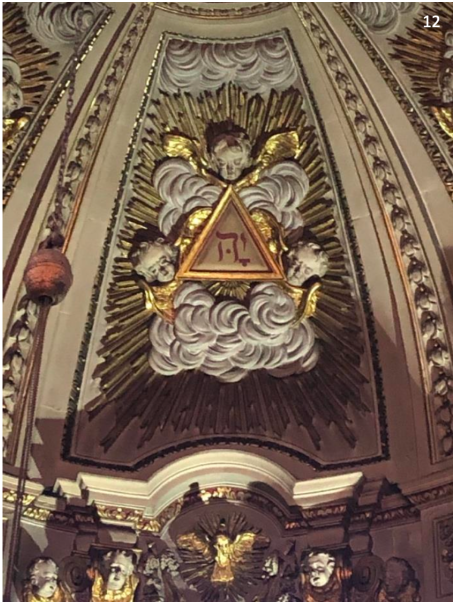

The shortened Hebrew name for God in a triangle in the apse at St-Mary-Le-Strand Church

IMAGE CREDIT: author

Above the church altar Gibbs makes a direct reference to God by including Hebrew letters YAH, the first syllable of the name YAHWEH, or JEHOVAH in a flaming triangle accompanied by cherub heads in clouds and sunbursts. Beneath is a dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit.

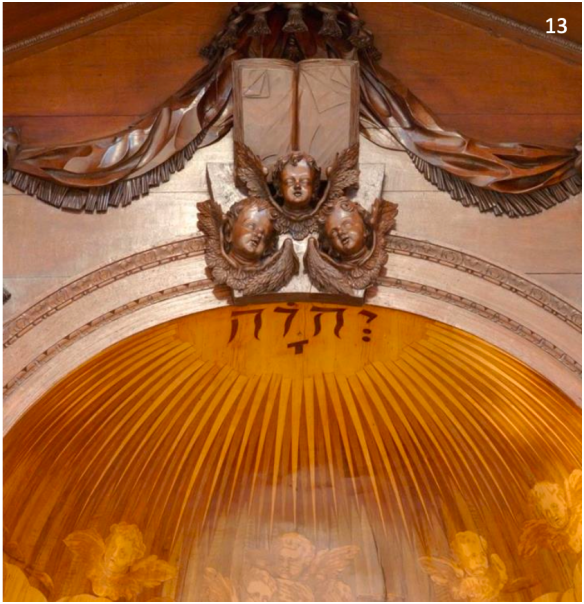

At his church St George’s, Bloomsbury, Gibbs’ fellow architect, Nicholas Hawksmoor, used the full four- character Hebrew name for God below three cherub heads in the eastern apse (it is sometimes called the Tetragrammaton).

It is surrounded by a sunburst, ‘a symbol that would become a prominent Freemasons sign’. [24]

The four character Hebrew name for God in the apse at St George’s, Bloomsbury.

IMAGE CREDIT: author

Maybe Gibbs and Hawksmoor were ‘brothers’ [25] and had more in common than just being Surveyors to the New Churches Commission? [26]

All photographs by Ricky Pound with the exception of photos 2, 3, 7, 8, 11 & 13.

Footnotes

Bibliography

Bibliography

Churton, Thomas, The Magus of Freemasonry – The Mysterious Life of Elias Ashmole – Scientist, Alchemist, and Founder of the Royal Society (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2004).

Colvin, Howard, Essays in English Architectural History (London: Yale University Press, 1999) Colvin, Howard, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600-1840 (London; John Murray,

fourth edition, 2008).

Curl, James Stevens, The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry (London: B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1991)

Curl, James Stevens & Wilson, Susan, The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015 edition).

Dyer, Colin, Symbolism in Craft Freemasonry (Shepperton: Lewis Masonic Ian Allan Regalia Ltd, 1983)

Friedman, Terry, James Gibbs Architect, 1682-1754 ‘a man of great’ (exhibition catalogue, published by the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Library Department, 1982).

Notes

Notes

1 I would like to thank Stewart Trotter and Peter Babington for inviting me to Mary-Le-Strand Church to look at the wall carvings and providing me with a marvellous tour of the church. Thanks also to Janis Booth for proofreading this paper and to architectural historians Richard Hewlings, William Aslet and author Keith Marsha Schuchard for their remarks and suggestions.

2 For the origins of Freemasonry see Professor James Stevens Curl, The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1991).

3 For the prolific career of Nicholas Hawksmoor, see Vaughan Hart, Nicholas Hawksmoor: Rebuilding Ancient Wonders (London: Yale University Press, 2002).

4 For James Gibbs strong Jacobite sympathies, see Murray Pittock, Material Culture and Sedition, 1688-1760. Treacherous Objects, Secret Places (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), pp.49-55.

5 Following the failure of the restitution attempt of 1715, Mar fled to France where he spent the rest of his life. It has been written by Whig historians that he earned the nickname ‘Bobbing John’ due to his habit of swapping allegiances between Houses of Stuart and Hanover. However, the nickname in Scotland was one of affection, ‘given without any political connotation, because Mar had a spinal deformity that caused his head to bob when he walked’ (see Stewart below). He maintained contact with Gibbs who wanted to visit him following his exile but was persuaded out of the venture by friends who rightly believed it would have a detrimental effect on his standing and reinforce suspicions of his Jacobitism. Despite living a life in exile Mar still continued to design architecture and offer his advice, including designs for a royal Palladian palace in Green Park for the Stuarts once they returned from exile. See Margaret Stewart, The Architectural, Landscape and Constitutional Plans of the Earl of Mar, 1700-32 (Dublin:

Four Courts Press Ltd, 2016). Gibbs remained forever faithful to his friend and in his Will left Mar’s descends property and money.

6 See Howard E Stutchbury, The Architecture of Colen Campbell (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1967), p. 23.

7 Stutchbury, The Architecture of Colen Campbell, p.23.

8 Under Robert Walpole the situation for the Tories would become untenable. See Eveline Cruickshanks, Political Untouchables:The Tories and the ’45.

9 Gibbs described St Mary-Le-Strand as

10 For example, Lord Burlington managed to secure important positions for several of his circle of architects, including William Kent (1685-1748), Henry Flitcroft (1697-1769), Isaac Ware (1704-66) and John Vardy (1718-65), within the Office of Works. See Howard Colvin, ‘Lord Burlington and the Office of Works’ in Essays in English Architectural History (London: Yale University Press, 1999), pp. 263-267. Gibbs started to include staple Palladian features such as the Diocletian and Serlian windows.

11 Such was Campbell’s dislike of Gibbs and his architecture that he criticised Gibbs’ Italian teacher Carlo Fontana in his Vitruvius Brittanicus (1715) and did not include any of Gibbs architecture in the publication.

12 Gibbs’ Book of Architecture, Containing Building and Ornaments (1728) was one of the most successful and widely read architectural treatise of the 18th century. It ‘reached far beyond the country gentlemen it was aimed at to India, South Africa, the West Indies and America where it was the primary source for the builders of the White House. There was also a copy in Thomas Jefferson‘s Library’.

13 A handful of known stonemasons are listed in Terry Friedman’s biography on Gibbs. See Terry Friedman, James Gibbs (London: Yale University Press, 1984, p.311-12.

14 There appears to be some evidence for a strong Scottish presence in this area. As Jerry White comments: ‘The Scots had a long history in London. They were even credited with joining the two cities of London and Westminster in the early seventeenth century, when ‘the great number of Scotch who came to London on the accession of James I (1603), settled chiefly along the Strand’. (Jerry White, London in the Eighteenth Century: A Great and Monstrous Thing, 2012, p. 94).

15 ‘Masonic lore identified the archetypical Temple of Solomon with a cube stone through its having modelled on the ‘cubic’ celestial temple of Revelation, and the cornerstone laid by masons in foundation rituals was thus by tradition cubic’ (Vaughan Hart, Nicholas Hawksmoor: Rebuilding Ancient Wonders (London: Yale University Press, 2002), p.94,

The Freemason Nicholas Hawksmoor employed the cube for his Church of St Mary Woolnoth. The Solomonic connection was reinforced there by the use of twisted Solomonic columns framing the altar. See Vaughan Hart, Nicholas Hawksmoor, 2002, p.94, 16 This dating has recently been challenged with the year of 1721 proposed.

17 Ashmole was a Royalist, astrologist and antiquarian. His initiation into Freemasonry took place at Warrington in July 1646 and is recorded in his diary. See Tobias Churton, The Magus of Freemasonry- The Mysterious Life of Elias Ashmole- Scientist, Alchemist, and Founder of the Royal Society (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2004).

18 These three degrees, known of the ‘Craft’ degrees or ‘Blue’ degrees, from the early Eighteenth century consisted of ‘Apprentice’, Fellow Craft’ and ‘Master Mason’. See Jay Macpherson, The Freemasons, the Temple, and the Lost Ark (2014) (Lumen), 33, 153– 172. https://doi.org/10.7202/1026571ar

19 This is the belief of Mr Stewart Trotter.

20 Colin Dyer, Symbolism in Craft Freemasonry (Shepperton: Lewis Masonic Ian Allan Regalia Ltd, 1983), p.88.

21 Quoted in Colin Dyer, Symbolism in Craft Freemasonry, 1983, p.88.

22 In this respect the gallows square could also form part of the letter T and would be in the correct order of spelling.

23 Quoted in: ‘https://ota.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/repository/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12024/2901/swift12_23_2.xml?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

24 Vaughan Hart, Nicholas Hawksmoor, 2002, pp. 99-100.

25 ‘Brothers’ is a term of friendship and endearment by which Freemasons referred to each other.

26 According to Anderson’s Constitutions of 1738, James Gibbs was a Freemason (“Brother Gib, the Architect”). However, Jerry White writes that Gibbs was not a recorded Freemason. It is worth noting at this particular time that Lodge membership records were not a requirement and many men who may well have been Freemasons and not recorded in official, and often very fragmentary, documentation. To complicate the issue, some Lodge meetings took place outside of the remit of Grand Lodge and occasionally in temporary Masonic spaces, such as houses on country estates and buildings in their gardens. For example, a lodge meetings took place at Houghton Hall in 1731, and a room at the White House, Kew Gardens, was also used for Masonic gatherings and for the Masonic initiation of Frederick, Prince of Wales, in 1737.

About the Author

Ricky Pound

Ricky Pound is an experienced heritage professional with over 23 years working and managing two of English Heritage’s 18th century Neo-Palladian mansions and their collections.

He regularly presents talks on 18th century architecture and has published papers on Masonic symbolism in art and architecture and Jacobite material culture.

Nicholas Hawksmoor – the ‘Devil’s Architect’

Nicholas Hawksmoor was one of the 18th century’s most prolific architects

more….

Recent Articles: in people series

Albert Mackey and the Civil War In the midst of the Civil War's darkness, Dr. Albert G. Mackey, a devoted Freemason, shone a light of brotherhood and peace. Despite the nation's divide, Mackey tirelessly advocated for unity and compassion, embodying Freemasonry's highest ideals—fraternal love and mutual aid. His actions remind us that even in dire times, humanity's best qualities can prevail. |

Discover the enduring bond of brotherhood at Lodge Dumfries Kilwinning No. 53, Scotland's oldest Masonic lodge with rich historical roots and cultural ties to poet Robert Burns. Experience rituals steeped in tradition, fostering unity and shared values, proving Freemasonry's timeless relevance in bridging cultural and global divides. Embrace the spirit of universal fraternity. |

Discover the profound connections between John Ruskin's architectural philosophies and Freemasonry's symbolic principles. Delve into a world where craftsmanship, morality, and beauty intertwine, revealing timeless values that transcend individual ideas. Explore how these parallels enrich our understanding of cultural history, urging us to appreciate the deep impacts of architectural symbolism on society’s moral fabric. |

Discover the incredible tale of the Taxil Hoax: a stunning testament to human gullibility. Unmasked by its mastermind, Leo Taxil, this elaborate scheme shook the world by fusing Freemasonry with diabolical plots, all crafted from lies. Dive into a story of deception that highlights our capacity for belief and the astonishing extents of our credulity. A reminder – question everything. |

Dive into the extraordinary legacy of Alexander Von Humboldt, an intrepid explorer who defied boundaries to quench his insatiable thirst for knowledge. Embarking on a perilous five-year journey, Humboldt unveiled the Earth’s secrets, laying the foundation for modern conservationism. Discover his timeless impact on science and the spirit of exploration. |

Voltaire - Freethinker and Freemason Discover the intriguing connection between the Enlightenment genius, Voltaire, and his association with Freemasonry in his final days. Unveil how his initiation into this secretive organization aligned with his lifelong pursuit of knowledge, civil liberties, and societal progress. Explore a captivating facet of Voltaire's remarkable legacy. |

Robert Burns; But not as we know him A controversial subject but one that needs addressing. Robert Burns has not only been tarred with the presentism brush of being associated with slavery, but more scaldingly accused of being a rapist - a 'Weinstein sex pest' of his age. |

Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse Discover the captivating story of Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse, the First Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Ireland, as we explore his rise to nobility, scandalous affiliations, and lasting legacy in 18th-century Irish history. Uncover the hidden secrets of this influential figure and delve into his intriguing associations and personal life. |

James Gibbs St. Mary-Le-Strand Church Ricky Pound examines the mysterious carvings etched into the wall at St Mary-Le-Strand Church in the heart of London - are they just stonemasons' marks or a Freemason’s legacy? |

Freemasonry and the Royal Family In the annals of British history, Freemasonry occupies a distinctive place. This centuries-old society, cloaked in symbolism and known for its masonic rituals, has intertwined with the British Royal Family in fascinating ways. The relationship between Freemasonry and the Royal Family is as complex as it is enduring, a melding of tradition, power, and mystery that continues to captivate the public imagination. |

A Man Of High Ideals: Kenneth Wilson MA A biography of Kenneth Wilson, his life at Wellington College, and freemasonry in New Zealand by W. Bro Geoff Davies PGD and Rhys Davies |

In 1786, intending to emigrate to Jamaica, Robert Burns wrote one of his finest poetical pieces – a poignant Farewell to Freemasonry that he wrote for his Brethren of St. James's Lodge, Tarbolton. |

Alex Lishanin explores Mumbai and discovers the story of Lodge Rising Star of Western India and Manockjee Cursetjee – the first Indian to enter the Masonic Brotherhood of India. |

Aleister Crowley - a very irregular Freemason Aleister Crowley, although made a Freemason in France, held a desire to be recognised as a 'regular' Freemason within the jurisdiction of UGLE – a goal that was never achieved. |

Sir Joseph Banks – The botanical Freemason Banks was also the first Freemason to set foot in Australia, who was at the time, on a combined Royal Navy & Royal Society scientific expedition to the South Pacific Ocean on HMS Endeavour led by Captain James Cook. |

Making a Mason in Prison: the John Wilkes’ exception? |

"To be a good man and true" is the first great lesson a man should learn, and over 40 years of being just that in example, Dr Buck won the right to lay down the precept. |

Elias Ashmole: Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer? The debate is on! Two eminent Masonic scholars go head to head: Yasha Beresiner proposes that Elias Ashmole was 'a Masonic hero', whereas Robert Lomas posits that Ashmole was a 'scheming chancer'. |

Sir Arthur Sullivan - A Masonic Composer We are all familiar with the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, but did you know Sullivan was a Freemason, lets find out more…. |

The Much-Maligned Dr John Misaubin The reputation of the Huguenot Freemason, has been buffeted by waves of criticism for the best part of three hundred years. |

Was William Morgan really murdered by Masons in 1826? And what was the lie Masonic author Rob Morris told? Find out more in the intriguing story of 'The Morgan Affair'. |

Lived Respected - Died Regretted Lived Respected - Died Regretted: a tribute to HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh |

Who was Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a Freemason, American Civil War Soldier, renowned sculptor ? |

A Masonic author and Provincial Grand Master of Forfarshire in Scotland |

Who was Philip, Duke of Wharton and was he Freemasonry’s Loose Cannon Ball ? |

Richard Carlile - The Manual of Freemasonry Will the real author behind The Manual of Freemasonry please stand up! |

Nicholas Hawksmoor – the ‘Devil’s Architect’ Nicholas Hawksmoor was one of the 18th century’s most prolific architects |

By Bro. Anthony Oneal Haye (1838-1877), Past Poet Laureate, Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, Edinburgh. |

The Curious Case of the Chevalier d’Éon A cross-dressing author, diplomat, soldier and spy, the Le Chevalier D'Éon, a man who passed as a woman, became a legend in his own lifetime. |

Mozart Freemasonry and The Magic Flute. Rev'd Dr Peter Mullen provides a historical view on the interesting topics |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device