Was ancient Egypt’s ‘village of the artisans’ the first operative stone masons’ guild?

And was their use of ‘identity marks’ a forerunner of the Mason’s Marks of the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages?

Read on for some possible answers…

‘The Place of Truth’ – Set Maat –is the ancient Egyptian workman’s village, nestled protectively into the foot of the Theban mountains on the west bank of modern-day Luxor.

Now named Deir el-Medina, the village was home to the artisans (known as Servants in the Place of Truth) who worked exclusively on the royal tombs of the pharaohs during the New Kingdom era of the 18th-20th Dynasties (c. 1550-1080 BC) a period of almost 400 years.

It could be described as one of the oldest known artisan communities, or ‘guild’.

Although the remains of a 4th Dynasty Old Kingdom ‘Worker’s Town’ has been discovered at Heit al-Ghurab, on the site of the pyramids at Giza, there is not the same volume of information available compared with that of the much later New Kingdom settlement at Deir el-Medina.

But what is evident, is that the skills of these master masons would have continued throughout the centuries, passed from father to son, master to apprentice.

What has been discovered at Deir el-Medina over the past century, has given us a unique insight as to how the later operative stonemasons guilds and lodges may have evolved from this remarkable civilisation.

There can be no doubt that the unprecedented influence and skills of the Egyptians, be it the sciences of mathematics, geometry, astronomy, or the artistry of their sculptors, painters, and scribes, travelled out of Egypt and across the globe prior to, and for centuries after, the end of their remarkable civilisation.

Whilst Freemasonry itself has no direct origins within ancient Egypt, we can gain insights from Deir el-Medina into how the many layers of practical traditions and religious practices of the Egyptians may have trickled down into modern-day Freemasonry via the travelling operative stone masons, the Renaissance trade in Egyptian antiquities, Masonic explorers who embarked on the ‘Grand Tour’ in the 18th and 19th centuries, and of course, the quasi-Masonic spiritual Orders whose imagination and conjecture knew no bounds.

The Workmen’s Village

Panoramic view (looking East) of the Workman’s Village at Deir el-Medina

PHOTO CREDIT: Philippa Lee

The site at Deir el-Medina was first excavated in earnest by Ernesto Schiaparelli between 1905-1909.

But it was the work started in 1922 by Bernard Bruyère, and continued by Jaroslav Černý that has given us the most comprehensive information yet as to the lives of non-royals in ancient Egypt.

Vast quantities (estimated in the region of five thousand) of pottery sherds or limestone ostraca were discovered in and around the village; they had been used for legal notes, lists, receipts, prescriptions, magical spells and so on.

Potsherds from the spoil heap at Deir el-Medina

PHOTO CREDIT: Philippa Lee

Larger pieces have been found that show sample inscriptions made by scribes, students, and those practicing their art before committing to the tomb walls.

An amusing example are the satirical ‘cat and mouse’ illustrations showing animals in reversed roles, one such cartoon depicts a cat as the servant of a mouse.

Cat and Mouse, ca. 1295-1075 B.C.E. Limestone, ink, 3 1/2 x 6 13/16 x 7/16 in. (8.9 x 17.3 x 1.1 cm).

PHOTO CREDIT: Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 37.51E. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum (Gavin Ashworth,er), 37.51E_Gavin_Ashworth_photograph.jpg)

The village was – and still is – a place of great importance. Located on the west bank of the Nile, the village was naturally protected by the Theban mountains to the north and the narrow valley in which it sits.

Obstructing a view of the river to the east is the hill known as Gurnet Murai, in which the tombs of the Nobles (officials) are situated.

To the west is the Valley of the Queens, ‘the Place of Beauty’, and to the east and south-east, the funerary temples of the pharaohs.

It is not an entirely hospitable area to have built a settlement; the unforgiving desert sun reflects off the surrounding mountains to the north, the hill to the east creates a barrier to any cool breeze from the Nile, and so at the height of summer it must have been unbearably hot.

Conversely, winter nights in the desert can reach very low temperatures, so it would have been a place of extremes to inhabit.

Al-Qurn (Ta Dehent) – meaning the ‘horn’, ‘peak’ or ‘summit’ is the highest point of the Theban Hills at 420 metres above sea level, and overlooks the village and the Royal Necropolis.

Reminiscent of a pyramid, and association to the Sun god Re, it is thought that the ancient Egyptians chose the area to bury their kings for this reason.

The area is sacred to the cobra goddess Meretseger, the patron and protector of the Worker’s Village; there is a shrine dedicated to her near the peak, close to a cobra-shaped rock.

Al-Qurn – ‘the peak’

PHOTO CREDIT: By Steve F-E-Cameron (Merlin-UK) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

To the north-east is the Ptolemaic temple dedicated to Hathor, built on the original site of a shrine to the great goddess, which during the Christian era was used as a church for the Copts, and the name Deir el-Medina translates as ‘monastery of the city.

Exterior of the Hathor Temple

PHOTO CREDIT: Philippa Lee

The oldest part of the village dates to the reign of Thutmose I (c. 1520-1492 BC) but it grew to its peak during the 19th and 20th Dynasty Ramesside Period between 1189 BC to 1077 BC, when it had around sixty-eight houses spread over 5,600 m2.

However, it was Amenhotep I, the father of Thutmose I whose first planned the site and for this reason, Amenhotep and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari were worshipped by the inhabitants throughout its history.

From the excavations there remains an entire layout of the living areas, plus the artisans’ tombs, with rock-cut shrines/chapels, some resplendent with pyramidions.

Several large tombs, especially those belonging to Sennedjem(TT1), Khabekhnet (son of Sennedjem, ‘Servant in the Place of Truth’ – TT2)– Pashedu (Craftsman – TT3), the tomb of Kha (a Foreman) and Merit (his wife – TT8), Ramose (‘Scribe in the Place of Truth’) who built three tombs – TT7, TT212 and TT250, and Nakhtamon (TT335) are sublime in their design and decoration; they are the most incredible legacy of these exceptional artists.

The Tomb of Nakhtamon (TT335)

PHOTO CREDIT: Philippa Lee

Due to the restricted shape of the valley there was not much room to move between the tightly packed houses – the layout has been compared to the skeleton of a fish, with the backbone running the length of the village as a main street and the blocks of houses spiking off to the left and right.

The streets were compact to say the least, and if you stretched out both arms you would have been able to touch the houses on each side; it would no doubt have been quite literally a very close knit community.

…

PHOTO CREDIT: Philippa Lee

To counteract the alternate suntrap days/freezing nights in the desert valley, the homes of the villagers were constructed of mudbrick on stone foundations.

The external walls were rendered with mud and whitewashed to reflect the sun; windows were cut high in the walls so as not to overheat the houses too much.

The houses were small consisting of four or five rooms: an entrance, a main room with a house shrine (or possibly a birthing bed) on a platform, two small rooms, a kitchen and cellar, and steps which led to the roof terrace where the inhabitants would no doubt have slept on summer nights.

We can easily imagine that the artisans decorated and modified their homes to perfection.

A model of the House of Ip(u)y

PHOTO CREDIT: Philippa Lee

Religion, as was the norm in ancient Egypt, was paramount – the workers comfortably worshipped their personal deities alongside the state gods and naturally the highest importance was placed upon the principles of maat – the cosmic principle of balance, truth, justice and order.

There were between sixteen and eighteen chapels dedicated to various deities including Ptah (the patron god of craftsmen and architects), Thoth and Seshat (both deities associated with wisdom, writing, record keeping etc), female-orientated goddesses such as Hathor, Tawaret and Bes (protectors of home, pregnancy, childbirth and children) and, Renenūtet (the goddess of the harvest), and last but not least, one of the most important deities – Meretseger (‘She Who Loves Silence’) the patron and protector of the artisans and their village and that of the entire Theban Necropolis.

Ostracon depicting Meretseger, protector and patron goddess of the Worker’s Village

PHOTO CREDIT: By Djehouty – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Set apart from any other settlements, the village is thought to have been deliberately difficult to access due to the vitally important and secretive nature of the work carried out by the workers.

The construction and decoration of the royal tombs was not merely a highly skilled job but the necessity for secrecy and protection was paramount.

The Place of Truth was protected by an ‘elite paramilitary police force’ known as the Medjay, who patrolled the mountain pathways from the village to the royal necropolis known to us as the Valley of the Kings.

Entry to and from the settlement was strictly monitored, which was necessary, not only for the workers but also because water, food and even laundry services were provided by labourers from outside the village; the nearest well – or the Nile itself – was a thirty-minute walk, so daily deliveries by external carriers were vital for the villagers.

There has been conjecture (most frequently in fictional works) that passwords and or identifying signs may have been used as a way of legitimate access to and from the settlement.

However, from texts written on ostraca we do know that there were ‘guardians’, ‘door-keepers’, and ‘Medjay of the Tomb’, which no doubt were needed not only to protect the village from intruders, or ensure that pharaoh’s sacred resting place was secure, but also to deter thieves from stealing the workers’ food rations, their valuable copper tools, and of course, any gold and precious metals. [i]

In that we can perhaps get a sense of the later use of ‘Tilers’ to protect lodges from eavesdroppers, or Cowans.

The community also had its own court of law, whose officers were made up of the elders of the village.

From a sociological point of view the workers would be considered middle class; they were salaried employees of the state and as such they received wages/rations three times higher than a manual worker such as a farm labourer.

They lived, and loved, much as we do now; marriages were mainly monogamous, although there was the freedom to divorce, and/or remarry; they were largely literate, including the women, many of which were associated with a particular deity and held positions such as chantress or singer of the god/goddess.

The women of the village had government supplied servants to help with domestic chores such as laundry and the grinding of grain, but as ‘Mistress of the House’ they were in charge of the important tasks of baking bread, brewing beer, and caring for the children.

The Workers

The inhabitants of the village were a mixture of Egyptians, Nubians (of which the Medjay were formed) and some Asiatics. These men were assigned to one of the most important tasks in the whole of Egypt – the construction and decoration of the eternal resting place of the king.

The name of the village – the Place of Truth – reflected this importance, for the concept of maat (Truth and Justice) was paramount to the survival not only of Egypt but the entire universe.

Upholding these societal and spiritual morals, was not just the task of the people but the prime function of pharaoh – it was a symbiotic flow of vital cosmic energy between the gods, the ruler, and his people.

Therefore, to be tasked with creating a ritualistic dwelling for the king to rest in eternity for ‘millions of years’, was not just a job, but a religious and civic privilege.

The groups of men designated this monumental task were called ‘the gang of the tomb’, and the ‘gang’ was divided into two ‘sides’ – the ‘left’ and the ‘right’; the right side was apparently given precedence when working.

The foreman (one for each ‘side’) was called the ‘Captain (of the Tomb)’ – these usually nautical terms have been noted as such and the etymology of the Egyptian words for ‘gang’ and ‘crew’ were used on both land and sea. [ii]

In his book, Černý covers the subject in meticulous detail, and it is replete with a fascinating (but not exhaustive) list of the known members of the village during the Ramesside Period.

There were also ‘two deputies (of the gang)’, and very importantly, two administrative scribes, one of each assigned to the ‘left’ and ‘right’ sides.

The scribes kept a tight tally on all the tools, paints, lamp oils and wicks, and of course the wages and food rations for each gang member.

Ostracon of a stone mason, c. 1295 – c. 1186; bequeathed by Gayer-Anderson, R.G. (Major), 1943 [E.GA.4324a.1943]

PHOTO CREDIT: Fitzwilliam Museum AC: 2294696 – museums collection

Each worker would be skilled in specific jobs, and these skills and positions were most often hereditary.

The records compiled by Černý over 50 years of research at Deir-el Medina, indicate numerous examples of fathers passing their trade on to their sons, most living and working in the village until their death.

This hereditary arrangement most likely added to the much-needed security, and maintained strong bonds to the village.

Aside from the Foremen and Deputies, there were:

Quarrymen – their job was the most arduous, carving deep into the mountain using a range of picks, chisels, mauls, and copper adze.

Their spoils would then be hauled away by labourers, piled high in woven reed baskets.

Their work was not merely to hack out the rock – it had to be meticulously precise and strongly protective, not just from the threat of tomb robbers but also from the rare yet massively destructive flash floods that could appear from nowhere and devastate the wadi tombs.

Workman’s Adze c. 1550-1295 New Kingdom.

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

Stone masons – who would move in to smooth out the rough surfaces; forming doorways and ceilings, niches, and pillars, as the quarrymen moved deeper into the bowels of the earth, creating mathematically precise chambers and corridors to the final space where the king would be laid to rest.

Plasterers – once the debris and dust from the quarrymen and the stone masons had settled, the plasterers could make perfect the walls and ceilings of the tomb.

A lime base coat would be applied and then layers of burnt gypsum, giving a three-coat plasterwork that is still used today.

This formula was so strong that it is of no surprise that so much of the exquisite tomb art is still so beautifully preserved.

Scribes / Draughtsmen / Artists – the plasterers moved on leaving the smooth walls for the draughtsmen/scribes/artist (all of which were interchangeable descriptions) to ink out their gridlines in preparation for the intricate decorations.

Pigments in earthy or jewel-like hues would be ground, inks and paints expertly blended, and gold leaf or powders prepared.

This was the point when the empty tomb would most likely fall silent; the masons with their tools and clouds of dust gone, and the ritually precise artwork could be completed in companiable reverence.

No doubt prayers and offerings to Ptah and Thoth would be made not only by the workers, petitioning their patron deities to oversee their precious work but also by visiting priests, eager to keep a watchful eye on the artisans to make sure that all the spiritual needs of the pharaoh would be attended to in the convoluted and precise symbolism that would ensure his graceful – and safe – passage to the underworld, united in eternity within the realm of the gods.

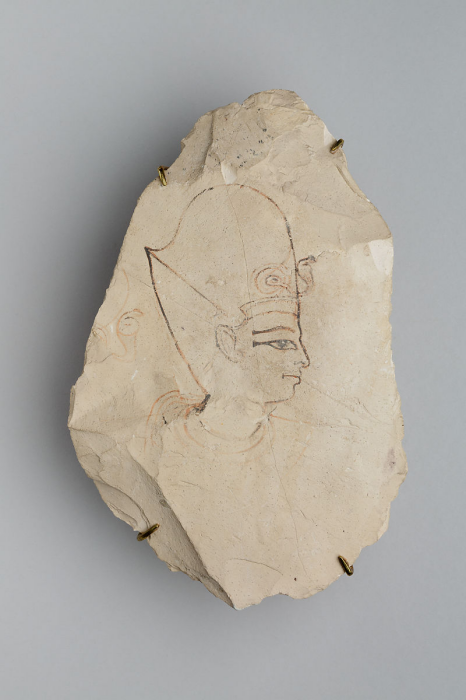

Ostracon Depicting a King’s Head ca. 1295–1070 B.C.

PHOTO CREDIT: New Kingdom, Ramesside, probably from Deir el-Medina.

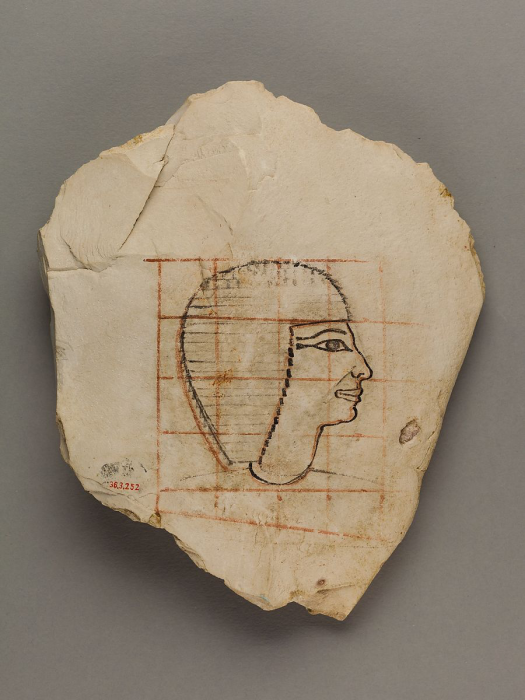

Artist’s Gridded Sketch of Senenmut ca. 1479–1458 B.C. New Kingdom

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

Carpenters, potters, and sculptors – these workers may have been from the village or brought in from the workshops attached to the temples or palaces further afield.

Their contribution to the immense task of furnishing the pharaohs’ tombs was to create coffins and sarcophagi, statues of deities, funerary items, and furniture.

The king would need all his earthly necessities and luxuries to accompany him in the otherworld.

Medjay of the Tomb – the police force that patrolled the village, the mountains, and the valley.

Their lookout posts were dotted along the winding path from the village to the tombs, with one main fortress at a mid-point, which was also where the workers set up their overnight camp.

Servants of the gang – those who would assist in any aspect of labour associated with the assorted workers; plus, those who brought cooked food, beer, and water rations daily from the village to the parched and hungry workers.

It is entirely possible that several of the female servants may have been there to help pass the nights for some of the workmen.

Rather than walk back and forth to the village every day at dawn and dusk, the men had their own smaller settlement on the mountain, along with buildings to store their tools, valuable lamp oil, and food and drink rations.

There are ostraca records that attest to many different situations that occurred during the working day, from the daily registers, tallies, and orders for new tools and provisions, to the recording of visits from wives, evenings spent drinking beer, and the occasional report of irregularities or complaints made against a worker or servant.

The gangs had a working rota of eight days on, two days off, and extra days would supplement this when there were state festivals, of which there were a lot (the Egyptians loved to party!)

They would stay at the settlement, often for the entire working week, returning to their family in the village for two days of rest or leisure, which was often used to work on their homes, or their own or others’ tombs.

Having a secondary job was not unheard of and these could range from making small items of furniture or other household items, the scribes might read / write / transcribe letters for those who weren’t literate, and the artists would decorate homes or other villager’s tombs – a system of barter was the norm in Egypt and it was the perfect way to trade for the artisans.

Shabti box and shabtis of members of the Sennedjem tomb c. 1279-1213 BC

Essential items of funerary equipment from the New Kingdom on, shabti figures, of which there could be from 1 to over 400 examples in a single tomb, were meant to substitute for the deceased whenever he or she was called upon to perform manual labour in the afterlife.

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

This wonderful social microcosm existed for just under four hundred years within the majestic macrocosm that was the New Kingdom of Egypt – an era that produced thirty-three different rulers, all of whom would have needed their Place in Eternity.

Generations of workers witnessed a myriad of social and political celebrations and upheavals; they were forced out of their homes at times by encroaching enemies, and once by the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten, when he moved the workers to his new settlement at Amarna.

At other times during the reign of the Ramesside rulers, there was social unrest, food shortages, and late payments from the government meant strikes by the workers were not uncommon.

In around 1170 BC, year 25 of Ramesses III’s reign, it appeared that the upholding of maat was not a priority for either the state, or for some of the workers.

When the system to pay the workers broke down, it was not seen as just dereliction of an employer’s duty, it was regarded as betrayal of maat.

What may have been the first ever recorded sit-down strike occurred when the workers, exasperated by the lack of supplies and wages, walked off the job.

Letters to the vizier were written, pleas from the village elders were dismissed and the men refused to return to work until their wheat rations were restored.

This was not the last strike to occur but normalcy returned for a period of years, until things turned distinctly sour.

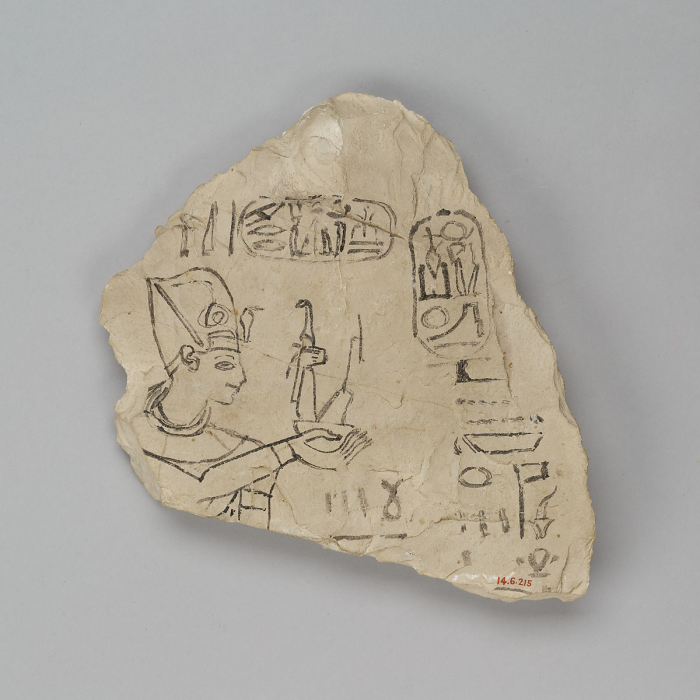

Ostracon Depicting Ramesses IX offering maat to the gods attributed to the chief draftsman Amenhotep c. 1126–1108 B.C. New Kingdom, Ramesside. Davis Collection. Accession Number: 14.6.215

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

Some of the workers decided to betray their obligations (and their principles of maat) and in one well-documented case during the turbulent reign of Ramesses IX (see the Amherst Papyrus) a mason at the village, named Amenpanufer, confessed to robbing the tomb of King Sobekemsaf II along with several others.

Sadly, this was not an isolated case, and by 1100 BC it became obvious that the Place of Truth was no longer the place to live – the betrayal of the supposed guardians of the royal necropolis was the death knell for an already ailing community.

These problems combined with the weak government unable to prop up a now bureaucratic nightmare, and the threat of attack from Libyans, prompted the workers to leave the village, seeking sanctuary within the walled fortress at the mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu.

The village remained deserted until the Coptic monastery was established within the Hathor temple during the 4th century AD. After the monks left, the village fell into obscurity.

Recent Research into ‘Identity Marks’ of the Deir el-Medina Artisans

Aside from the fascinating creative, social and practical aspects of the workmen’s lives, there have been some recent intriguing discoveries regarding the ‘identity marks’ of the necropolis workmen.

Identifying marks used by stone masons are well-documented from the Middle Ages onwards but the use of ‘marks’ by the tomb makers, not only give us a fascinating insight into the language of pictograms used by early civilisations, but it is also a valuable tool in understanding the probable origin of the use of masons’ marks in later years.

One of the common hypothesises is that masons’ marks were used due to illiteracy, in a way similar to the way those who could not read or write would make their mark with an ‘X’ as their signature.

But a recent project entitled ‘Symbolizing Identity. Identity Marks and their Relation to Writing in New Kingdom Egypt’, led by Egyptologist Ben Haring at Leiden University, researched the use of workmen’s marks found on ostraca, graffiti and in the tombs of the workers.

The researchers discovered evidence of non-textual ‘identity marks’ used by the highly literate New Kingdom artisans and have investigated their usage not only in a linguistic sense but also in the social and administrative background. [iii]

Research carried out by PhD student Kyra van der Moezel concluded that the identity marks continued to be used long after the more common usage of writing in the form of hieratic, she states that:

People often assume that identity signs are ‘more primitive’ than written language, and that writing will slowly but surely take over from symbols. However, what we see is that writing and symbols continue to exist alongside one another. There is some interchange between the two, but symbols have never been ousted as a means of communication. Symbols continue to be useful because you can express a lot more in a single symbol than in a letter or a word. [iv]

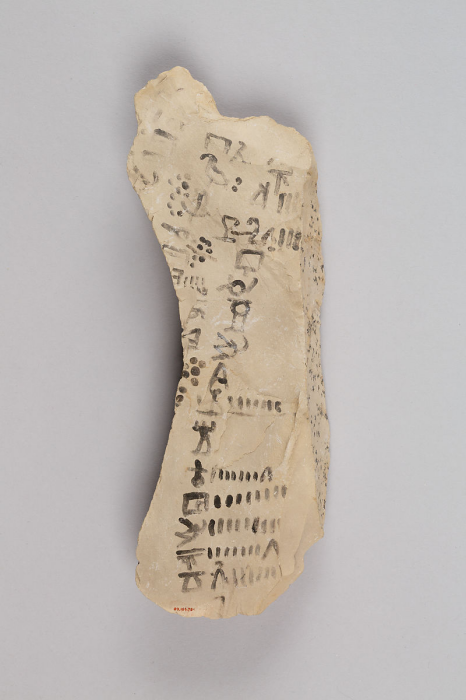

Examples of Workmen’s Identity Marks found on ostraca at the site of the village at Deir el-Medina:

Limestone ostracon with Workmen’s Identity Marks c. 1390–1352 B.C New Kingdom, reign of Amenhotep III. Excavated by Theodore M. Davis in the Valley of Kings, Thebes. Allotted to Davis by the Egyptian Government in the division of finds. Given by Davis to the Metropolitan Museum in 1909. Accession Number: 09.184.700

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

Limestone ostracon inscribed with identity marks c. 1126–1070 B.C. New Kingdom, Ramesside – reigns of Ramesses IX – Ramesses XI. Excavated by Theodore M. Davis in the Valley of Kings, Thebes and donated to the Metropolitan Museum in 1909. Accession Number: 09.184.784

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

Evidence of ‘identity marks’ in the Old Kingdom – the Age of the Pyramid Builders (c. 2700–2200 BC)

However, delving further, there are references to the use of identity marks that date back to the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom.

Maspero in his History of Egypt writes of the stone masons who worked on the Great Pyramid of Khufu:

The Great Pyramid was called Khult, the “ Horizon ” in which Khufui had to be swallowed up, as his father the Sun was engulfed every evening in the horizon of the west. It contained only the chambers of the deceased, without a word of inscription, and we should not know to whom it belonged, if the masons, during its construction, had not daubed here and there in red paint among their private marks the name of the king, and the dates of his reign.

His notes continue:

The workmen often drew on the stones the cartouches of the Pharaoh under whose reign they had been taken from the quarry, with the exact date of their extraction; the inscribed blocks of the pyramid of Kheops bear, among others, a date of the year XVI.

It seems that the use of identity marks was a common practice amongst the quarrymen and stone masons, and there is some evidence that the marks were passed down from generation to generation.

More importantly, it appears that the marks are not part of an ‘alphabet’, but distinctive symbols most likely created by the user.

Use of identity marks in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040-1782 BC)

The stone mason’s chisel pictured below is from the 11th Dynasty reign of Mentuhotep II and is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The text accompanying the image states that:

This chisel was clearly made for use and looks as if it has indeed been used.

It was found in a tomb that contained at least six burials but no object of demonstrably post-Mentuhotep II date.

There was even a piece of linen marked for Mentuhotep II’s wife Queen Neferu.

The mark incised into the chisel was previously understood to represent the pyramid which Museum excavator Herbert E. Winlock and others thought had originally existed above the solid core structure of the temple of Mentuhotep II at Deir el-Bahri.

The existence of this pyramid has been put into doubt, however, although renewed discussions are under way.

The mark also occurs on linen sheets from the tomb of the “Slain Soldiers” (MMA 507 see here 27.3.84-134), which has been shown to be of the time of Senwosret I, and on another piece of linen found at Lisht South close to the pyramid of that king.

The sign can, therefore, no longer be exclusively associated with the temple of Mentuhotep II at Deir el-Bahri, even if this particular chisel was made and used during that king’s reign.

The mark’s form and purpose remain enigmatic.

Hammered bronze or copper alloy Stone Mason’s Chisel ca. 2051–2000 B.C. Middle Kingdom.

Upper Egypt, Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb MMA 101, in front of chamber 3 west, MMA excavations, 1926–27. Accession Number: 27.3.12

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

The association of the mark on the chisel with those found on linens ascribed to Queen Neferu in MMA101, and also to those within tomb MMA 507, is intriguing.

Tomb MMA 507 is known as the tomb of ‘The Slain Soldiers’ at Deir el-Bahari and dated to the 12th Dynasty. Within the tomb was a mass grave of approximately 59 soldiers wrapped in linens.

LEFT: Linen mark (type V) ca. 1961–1917 B.C. Middle Kingdom, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb MMA 507 (The Slain Soldiers), MMA excavations, 1926–27

RIGHT: Linen mark (type XXXVII) ca. 1961–1917 B.C. Middle Kingdom, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb MMA 507 (The Slain Soldiers), MMA excavations, 1926–27

PHOTO CREDIT: Met Museum OA PD licence

Conclusion

Although we have no concrete proof that any direct influence and/or traditions of the ancient Egyptian artisans of Deir el-Medina filtered across the globe to be incorporated into the communities or guilds of the operative stone masons, it is fascinating to see the similarities in both the social and administrative areas of the community, and particularly regarding the use of their identity marks.

As always, with any research, we need to keep a level head and remember that correlation does not imply causation however exciting the evidence may look…but it is fun to explore.

In a follow-up article, the use of quarry and masons’ marks will be explored further, and a comparison between the ancient Egyptian marks and those recorded from the middle ages onwards.

Footnotes

Reference

NOTES:

[i] Černý, Jaroslav. A Community of Workmen at Thebes in the Ramesside Period, Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1973

[ii] Ibid, pp. 99-104

[iii] Leiden University Research Project https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/research/research-projects/humanities/symbolizing-identity-identity-marks-and-their-relation-to-writing-in-new-kingdom-egypt

[iv] Van der Moezel, Kyra ‘Symbolizing identity: Identity marks and their relation to writing in New Kingdom Egypt’ https://www.heritagedaily.com/2016/08/symbolizing-identity-identity-marks-and-their-relation-to-writing-in-new-kingdom-egypt/112558

Article by: Philippa Lee. Editor

Philippa Lee (writes as Philippa Faulks) is the author of eight books, an editor and researcher.

Philippa was initiated into the Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons (HFAF) in 2014.

Her specialism is ancient Egypt, Freemasonry, comparative religions and social history. She has several books in progress on the subject of ancient and modern Egypt. Selection of Books Online at Amazon

Additional Research

Ancient Lives series 1-4 (this series accompanies John Romer’s book Ancient Lives – The Story of the Pharaohs’ Tombmakers ) – (Youtube Video – 55mins approx)

How did ordinary Egyptians live in the time of the pharaohs?

Renowned British Egyptologist John Romer explores the ruins of an ancient village just outside Thebes, where generations of craftsmen and artists built and decorated royal tombs.

There, relics reveal the most intimate details of the people’s daily lives: their meals, their loves, their quarrels, and even their dreams.

Go inside the pharaohs’ most magnificent tombs and see astonishing art and priceless treasures.

Meet the scribes, stonemasons, and high priests who presided over this city of the dead. Learn the secrets of the tomb raiders and the tricks devised to thwart them.

This four-part series provides fascinating insights into a civilisation now lost to the ages.

Articles

Leiden University Research Project https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/research/research-projects/humanities/symbolizing-identity-identity-marks-and-their-relation-to-writing-in-new-kingdom-egypt

Van der Moezel, Kyra – ‘Symbolizing identity: Identity marks and their relation to writing in New Kingdom Egypt’

https://www.heritagedaily.com/2016/08/symbolizing-identity-identity-marks-and-their-relation-to-writing-in-new-kingdom-egypt/112558

From Single Sign to Pseudo-Script

By: Haring Ben

From Single Sign to Pseudo-Script by Ben Haring presents a well-documented and illustrative example of the use and development of identity marks, whose unique and universal features are brought out by a combination of Egyptological, comparative and theoretical approaches.

Identity Marks in Deir el-Medina During the Ramesside Period:

By: Daniel Soliman

This book is the first in-depth analysis of the historical and functional context of the identity marks in and around Ramesside Deir el-Medina. In the first chapter, key objects inscribed with identity marks are discussed to reveal the workmen behind numerous identity marks.

This analysis is based on the archaeological and textual evidence from the community. The second chapter studies the use of identity marks as property markers and votive graffiti, and investigates the marks’ function in administrative documents.

These documents, drawn up in addition to the well-known hieratic administration, are deciphered for the first time. The third chapter revolves around the use of the identity marks in the context of literacy.

It demonstrates that the marks where predominantly employed by workmen without scribal training, who amplified their documents with self-invented signs and signs borrowed from script.

The final chapter presents conclusions regarding the use of the marking system, the conception of new marks, and the transference of marks from workman to workman and from one generation to another.

It argues that scribal practices deeply rooted in the community stimulated the invention of different ways of employing identity marks.

Recent Articles: Freemasonry and Egypt

Over time many Masonic Rites have developed, each Rite having its own history, legends, and rituals. Some of them are still practiced today, and others have ceased to exist. The best known and at the same time the most practiced Masonic Rites are the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite and the York Rite. Among other Masonic Rites, we can find the Rite of Memphis, to which this article is dedicated. The Rite of Memphis is a branch of Esoteric Freemasonry and specifically one of the Rites of Egyptian Freemasonry. |

Mason's Marks – from Egypt to Europe? Mason's marks have been a source of intrigue, not only to Freemasons but to historians and archaeologists. The use of simple pictograms have been employed for millennia by artisans to identify their work. But where did they originate and why? |

Egypt's 'Place of Truth' - The First Operative Stone Masons' Guild? Was ancient Egypt's 'village of the artisans' the first operative stone masons' guild? And was their use of 'identity marks' a forerunner of the Mason's Marks of the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages? Read on for some possible answers… |

Masonic Miscellanies - Freemasonry & Bees Freemasonry & Bees - what's the buzz? The bee was among the Egyptians the symbol of an obedient people, because, says Horapollo, of all insects, the bee alone had a king. |

A look at the fascination with Egyptomania and Masonic Temples in Australia |

We take a look at the archaeological connection with the Craft, first published in The Freemason's Chronicle - January 30, 1875 |

Book Intro - Hidden Life of Freemasonry Introduction to The Hidden Life in Freemasonry (1926) by Charles Webster Leadbeater |

We explore fascinating and somewhat contentious historical interpretations that Freemasonry originated in ancient Egypt. |

Is Freemasonry esoteric? Yes, no, maybe! |

Egyptian Freemasonry, founder Cagliostro was famed throughout eighteenth century Europe for his reputation as a healer and alchemist |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device