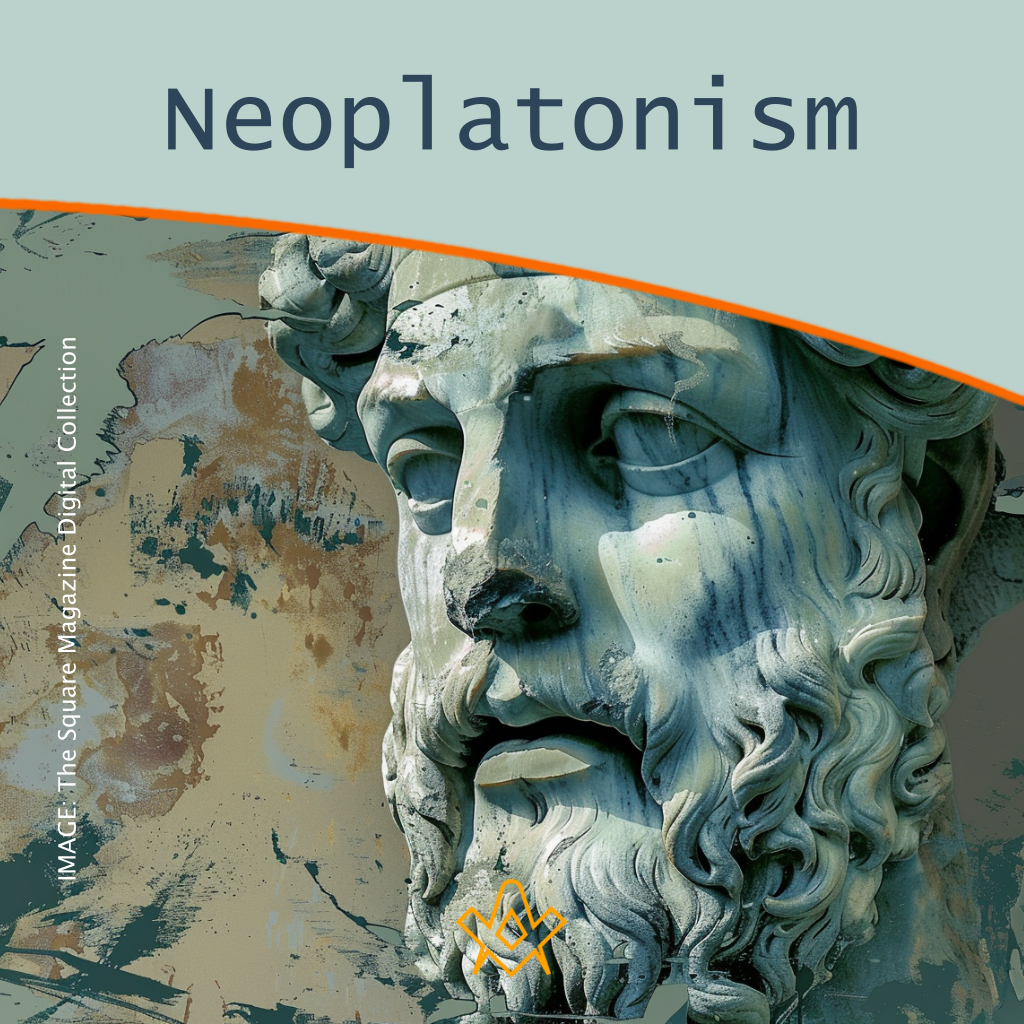

The term Neoplatonism is frequently used within the esoteric orders and societies, but very few people seem to understand what exactly it stands for, not least because it often has difficulties describing itself clearly!

Neoplatonism underpins so many aspects of modern esoteric thought, pervades Rosicrucianism, Martinism and the modern Gnostic Church, and has had a perennial influence on the development of philosophical concepts and ideas to the current day.

As a chronic student of Pythagorean and Neoplatonic philosophy for over 20 years, I hope here to explain what this term relates to, its history and background, and explain some of the most fundamental ideas that are proposed within this very indistinct school of philosophical thought.

Roughly speaking, the etymology of the term relates to the period of the influence of Plotinus, from the third to the sixth centuries of the Christian Era.

This was the dominant philosophy during the later period of the Roman Empire, and became a strong influence upon the Mediaeval Christian Church and also upon the early development of Islam.

Neoplatonism would go on to inspire and pervade the thoughts and writings of almost 2000 years of Western and Middle-Eastern philosophy, from Avicenna(950-1037CE), Moses Maimonides, Solomon ibn-Gabirol, al-Farabi, Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart (1260-1328CE), Marcelius Ficino and the Renaissance revival, and most importantly to this author, Baruch Spinoza (1632-77CE).

Neoplatonism was born from the succession of the Middle Platonists, primarily Plutarch (45-120CE) and Apuleius (120-170CE).

The Gnosticism of the first century of the Christian Era, which would later become declared heretical by the proto-orthodox Christians, effectively existed as a syncretic blend of the original Jerusalem Church, the pro-Hellenic Paulianity, enduring Platonic philosophy and Valentinianism, and Iranian or Mesopotamian Mandaeism.

The Manicheism expounded by Mani (214-276) in Persis, a dualistic and syncretic theology predicated by Mazdaism, bears close comparison to not only Gnosticism, but to the developing Neoplatonic concepts we will explore shortly.

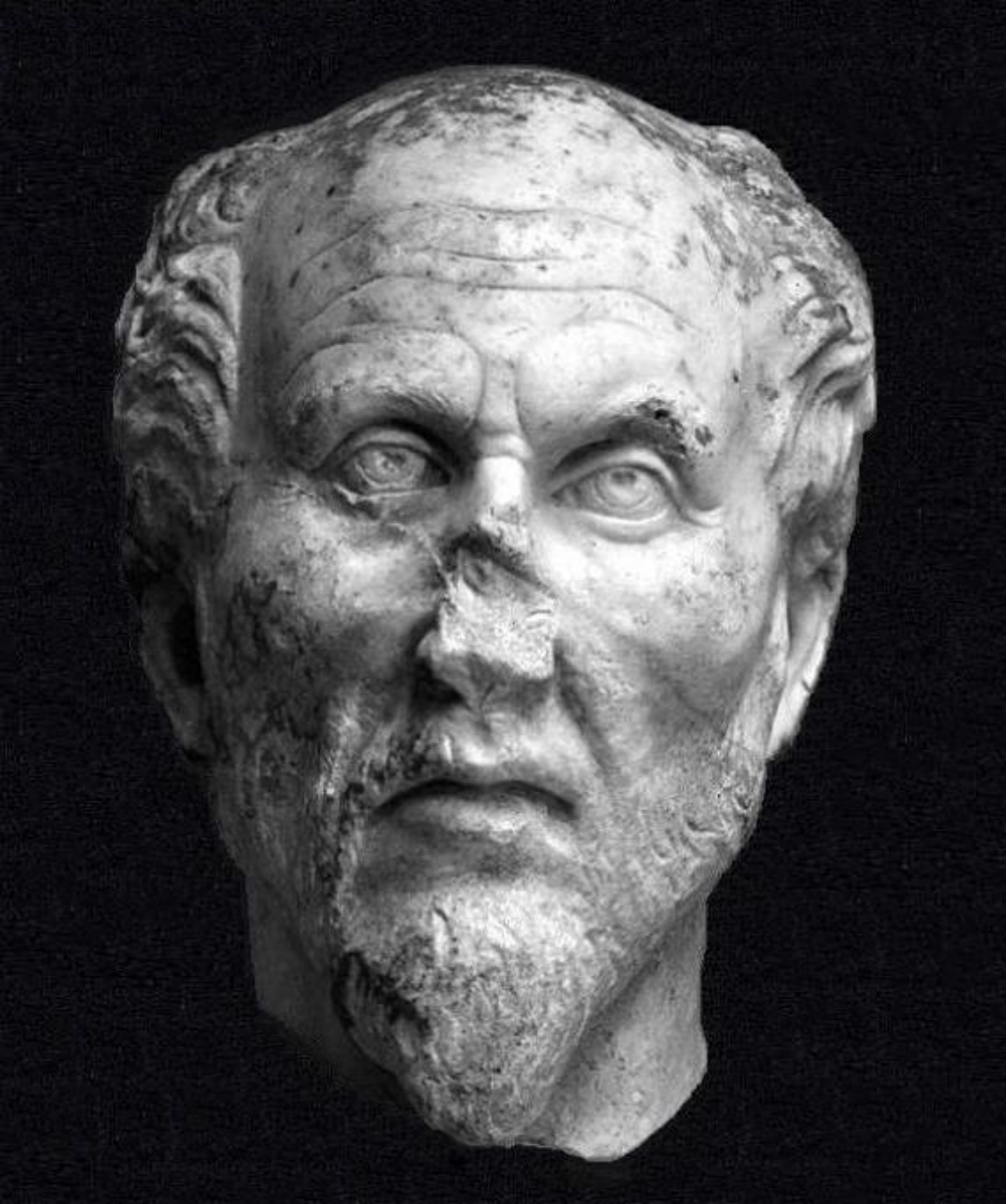

Plotinus (204-71CE)

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The first distinct step in the development of Neoplatonism lies with Ammonius Saccas (175-242CE), at the start of the third century. Saccas was an Alexandrian philosopher with a strong background from, or affinity with, India.

Saccas introduced the Hindu philosophy of the Vedanta to the post-Platonic Hellenic World and the still-developing Christian theology. Saccas taught several notable students, including both Origens.

However, his most important student was Plotinus (204-71CE). Plotinus, born in Lycopolis, Lower Egypt, at age 27 travelled to Alexandria in 232CE, and found in Saccas the teacher he had been seeking, and studied under him for 11 years.

At the age of 38, Plotinus joined the army of Gordian III, and travelled to Persia, in search of the Persian philosophers.

Two years later, he arrived in Rome, where he would spend the rest of his life, surrounded by attentive students, most notably Porphyry of Tyre (234-305CE), who would subsequently publish the Enneads of Plotinus, the only extant collection of his writings.

Plotinus taught that there was a supreme and transcendent One beyond all, containing no division and beyond all conceptualisation, and that this was not even simply the sum of all its expression. The One was the creative source and the teleological end of all.

The One emanated all, and the first such emanation was Nous; primal thought, intelligence, or reason. This is the first expression of the One, its ideal content, and therefore the Imago Dei, the image of God; and can thus further be conceived of as the Logos (Word) of God.

As we know, within the Prologue of the Gospel of St. John, the cosmogony of the early proto-orthodox Christian Church follows a strongly Platonic ontological, and metaphysical, view of causation.

The opening verse clearly agrees with this proposition of Plotinus, which is inherently Platonic, but critically, assimilating the objection by Aristotle to a ‘pre-creation’ state.

Simplistically, Neoplatonism took the teachings of Platonism, and infused them with the Greek Hermeticism of Egypt, and the Chaldean Oracles. Plotinus himself was anti-Gnosticism, or more specifically, anti-Valentinianism.

The latter held the concept that both the mundane and the celestial worlds were inherently impure and thus evil, whereas the evolving concepts in the Neoplatonic philosophy posited that the mundane world was a divine imitation of the ideal heavenly world, following the most primal dialectic of Plato.

Neoplatonism specifically focused upon the goal of Henosis, that is, of the unification of the individual with the One. This is the origin of the concept of the Microcosm, Man, as being a minute particle of the whole, the One, the Macrocosm. The Microcosm is God writ small.

The concept of Dualism is critical to the study of Hellenistic philosophy. Pythagoras declaimed that good and evil were opposite and independent. In his cosmogony, there was only one world or universe.

Plato however posited both a higher and lower Cosmos; a World of Forms (or Ideals), and a Material World. In contradistinction, the Pythagorean Evil comes from the One and is an independent and binary opposite; whilst in Neoplatonism, Evil arises from Good, as a relative less good or more evil expression, and is part of a spectrum rather than an antithesis.

For Plotinus, there was no such concept as a Principal or Primal Evil, no Dark Hyle. Therefore, to Plotinus, Evil was simply the complete absence of Good, as clearly described within Martinist theory.

This can be seen in the later development of the concept of the Qlippoth of the Kabbalah, whereby the opposite and ‘negative’ sephira on the Dark Tree of Life are recognised as shells or husks, devoid of the distinguishing characteristics of the ‘positive’ sephira.

One of the most profound concepts that would shape Platonic and Neoplatonic cosmogony, as well as Valentinianism and Gnosticism, was that of the Demiurge, often named Yaldabaoth. The Demiurge is descried by Plato as the ‘Divine Craftsman’, the creator of the Cosmos.

As the active participle of the One, the Demiurge is the consciousness, the Nous, or the energeia of Aristotle, the contemplative faculty or ergon of the One.

Plato argued in his Socratic dialogue Timaeus that there was a dialectic and a quarrel between poetry and philosophy, and that the Demiurge proved that philosophy was not equal to religion.

Herein Plato suggests that the Demiurge observed the Platonic Forms, and in consequence created the Cosmos. Aristotle, rejecting the cosmogony of the Timaeus however, argued that the Demiurge does not exist, but is in fact Intellect, or as he termed it, the Unmoved Mover.

As the cosmogony of the Timaeus demands a teleological definition of the Demiurge, Aristotle argued that a beginning of time was an impossibility, as “nothing can come from nothing”, and so a pre-creation state could not exist.

The concept of the Demiurge determined the dualistic cosmogony of the early Gnostic movements, most especially the Valentinian school, as well as the beliefs of later movements such as those of the Bogomils and the Cathars.

Essentially, if the Divine One is perfect, then everything else that He created is less perfect, and thus, by inference, less good. Hence, the early Gnostic concepts that the mundane or material world is in terms of relativity to God evil.

This concept pervades all Gnostic systems to a varying extent, and is the reason behind the oft quoted view that the Demiurge is evil, and even further, has been correlated with the development of the Lucifer concept.

Just as Monism predicates Dualism, if the One is perfect, then anything else is less perfect, and so this implies a binary opposition of existence and Platonic Forms through the cosmos and the celestial realm.

A number of the early Gnostic Gospels, most especially the Apocrypha of St. John, promote this binary division of Good and Evil, with Evil being represented by the Primal Archon, Yaldabaoth.

Christ is the Redeemer, being the divine power that can reunite the dualistic Gnostic view of Christianity and restore this to the Monad.

The material cosmos is here deemed to be transitory, henosis can only occur after death and the return to the Primal State.

Augustine, whose influence on the development of the Catholic doctrine cannot be overemphasised, incorporated this Manichean dualistic theophilosophy, and claimed that there was a dichotomy between the Monad and the primacy of the Divine World, and that of the Devil and his adversarial opposition to God.

He believed that God promoted the work of Redemption, but simultaneously combined this with the persecution of the family of Adam. Within Augustine we find the most probable root cause of the persisting dualistic theology of the evolved Christian Church today.

Aestheticism is the philosophical discipline focused upon the study of beauty, most primarily in art, nature, and good taste.

Two contemporary philosophical doctrines at this period in time were Stoicism, and Epicureanism, both focused on a most material interpretation of the world and life, and the denying of the concept that anything preternatural could exist.

The former took a more logical and (pre-Hegelianian) phenomenological approach, the latter a more hedonistic or at the very least, sensual, one, but both denied the aesthetic principle and value in the interpretation of the world.

However, Plotinus took the ideals of Plato, and applied aesthetic theory to these, proposing that Beauty was in fact a reflection of the One, and that Beauty was a means towards Unity with the One.

“Like anyone just awakened the soul cannot look at bright objects. It must be persuaded to look first at beautiful habits, then the works of beauty produced not by craftsmen’s skill but by the virtue of men known for their goodness, then the souls of those known for beautiful deeds…

Only the mind’s eye can contemplate this mighty beauty… So ascending, the soul will come to Mind… and to the intelligible realm where Beauty dwells” (Enneads I.6.9).

Within Neoplatonism, two elemental traditions exist, both aiming for the concept of Reintegration.

The first is theoretical, or philosophic, the second is theurgical. This latter term derives from the Greek concept of Theourgia, also known as Demiourgia, ritual practice, aimed at invoking the Divine power, towards the goals of the One and towards the reunification of the Cosmos with God.

Porphyry described this ritual working as the pious magic of God. Therefore, within these traditions, two separate dialectics develop, namely that between Poetry and Philosophy, and that between Nature and the Demiurge. The resultant of these is that Hypostasis, or the union of humanity and divinity, is equivalent to the concept of Salvation.

The development of the Theourgia-Demiourgia concept lead to the conclusion that Reason alone does not predicate Salvation.

This was supported by the Gnostic approach, which embraced not only philosophy and the Hieratic arts, but also the Chaldean Oracles, evocation, and magic.

In Neoplatonism, we recognise two main divisions, that of the philosophic, exemplified by Plotinus and Porphyry, and the Hieratic, expressed by Proclus, Iamblichus and Syrianus.

The former conceptualised the Demiurge as an inherent part of a dialectic hypostatic ontology after Plotinus.

The latter however focused far more upon a theological and theurgic methodology towards salvation. In the final classical period of Neoplatonism, Proclus concluded the development of the philosophy into one centred upon theurgy.

One can conceive that the development of Neoplatonic philosophy evolved from that of Plotinus, a rationalist, who stated that only Reason is free of magic, opposed by that of the Church, who stated that only Faith is free of magic.

Porphyry connected both systems, and this was synthesised by Iamblichus into a rational justification of theurgy.

This follows the dyad of Kant, and expresses clearly the thesis-antithesis-synthesis formulation of Johann Fichte. Plotinus believed that Reason alone could attain Henosis, whilst Iamblichus posited that Reason itself was not enough.

The fundamental principle which I would suggest critically defines Neoplatonism is the philosophical and theological concept that Salvation is a consequence and final achievement, not solely through Faith, but rather through Knowledge or Understanding.

This firmly establishes its direct correlation and symmetry with Gnosticism, and thus explains the pervasive influence that it has had on the development of theophilosophical soteriology over the last two millennia.

The books of the Nag Hammadi library, Gnostic theology and cosmogony, and Neoplatonic philosophy bear very strong similarities.

There is however a fundamental difference between Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. Gnosticism emphasises that the primal truth, and thus Salvation, can only come from Divine Revelation, and eschews philosophical analysis, which was the primary working tool of the Neoplatonists.

Early Gnostic belief, as far as can be generalised in this manner, concerns itself with the concepts of the unworthiness of the world, and the disassociation of God from his creation, Nature.

Gnosticism, therefore, provided an alternative to Pauline Christianity, emphasising the existence of both exoteric and esoteric knowledge, and the concept of a secret doctrine that could only be known through personal contact with God.

Somewhat paradoxically, Gnosticism emphasised the theories of both Plato and the Stoics, and expressed the continuation of a secret tradition running through human history.

In contradistinction to both Neoplatonism and to Pauline Christianity, the most profound difference within the broadest collectivity of Gnostic thought is that the Logos exists as a living person, not simply as a philosophical abstraction, nor a theological ideal that is unreachable except through Faith.

Hence, Gnosis crosses both streams, and unites the binary disparity of both.

In conclusion, Neoplatonism comprises a heterogenous admixture of philosophy and theology, and as such, inherently expresses one example of the metaphor that we find within the Kabbalah that one needs both a Pillar of Severity, and a Pillar of Mercy, to create in synthesis the Middle Pillar of Balance, by which means alone we may ascend to our eschatological henosis.

Plotinus interpreted Plato, enlightened by the Vedas, but rather than a defined and comprehensive philosophical system, this was effectively a portmanteau of open ideas, which would permit countless further generations of philosophers and theologians to freely interpret his propositions.

We find in Neoplatonism a philosophical explanation and proof for the belief in God, and in support of the most fundamental theology of the Christian Church, without needing to accept the subsequent dogma introduced for sociopolitical reasons over the last 2000 years.

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

Ayres L. Augustine and the Trinity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010.

Bamford C (Ed.). Homage to Pythagoras. Lindisfarne, NY. 1980.

Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy. Penguin. 1969.

Brons, D. Valentianian Monism. The Gnostic Society Library. ND. http://gnosis.org/library/valentinus/Valentinian_Monism.htm

Dancy J. An Introduction to Contemporary Epistemology. Blackwell. 1985.

Davis B. Philosophy of Religion – a Guide and Anthology. Oxford. 2000.

Dillon J. The Ideas as Thoughts of God. Etudes Platoniciennes (8) 31-42. 2011. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesplatoniciennes.448

D’Hoine P. The Intelligent Design of the Demiurge. On an argument from Design in Proclus. Etudes Platoniciennes (5) 63-90. 2008. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesplatoniciennes.842

Ehrman BD. Lost Scriptures. Oxford University Press. 2005.

Faivre A, Hanegraaff WJ. Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion. Peeters.1998.

Farrell L. Paulianity: Identifying Christianity’s False Apostle. 2014.

Fletcher MDA. Eschatology. Transactions of the SRIA Province of BC & Yukon. 2015/6.

Fletcher MDA. Martinist themes in Valentinian philosophy & cosmogony. Transactions of the SRIA Province of BC & Yukon. 2015/6.

Fletcher MDA. The Metaxis – Transcultural Interpretations of the Axis Mundi paradigm. Trans. SRIA Province of BC & Yukon. 2018.

Fletcher MDA. Pythagorean Musical Theory, and the Theophilosophical Attributions of Musical Mathematics and Harmony. Trans. SRIA Province of BC & Yukon. 2020.

Flew A (ed.). A Dictionary of Philosophy. Picador. 1984.

Fradon R. The Gnostic Faustus. Inner Traditions. 2007.

Gerson LP. Plotinus. New York. Routledge. 1994.

Gilbert RA. Gnosticism and Gnosis. Antioch. 2012.

Hampshire S. Spinoza and Spinozism. Oxford. 2005.

Haldane J. A Companion to Aesthetics. Blackwell. 1995.

Irenaeus. Against Heresies. ND. In Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 1. Roberts A (Ed.). http://gnosis.org/library/advh1.htm

Kamal M. Spinoza and the Relativity of Evil in the World. Open Journal of Philosophy, 8, 145-155. 2018. doi: 10.4236/ojpp.2018.83011

Kreeft P. A Shorter Summa. The Essential Philosophical Passages of St. Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica, Ignatius. 1993.

Kupperman JS. Living Theurgy: a Course in Iamblichus’ Philosophy, Theology & Theurgy. Avalonia. 2014.

Lowe EJ. A Survey of Metaphysics. Oxford. 2002.

Lupieri E. (trans. Hindley C). The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics. Grand Rapids, MI. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2002.

McKeon R (ed.). The Basic Works of Aristotle. Modern Library. New York. 2001.

Mead GRS. Fragments of a Faith Forgotten. Theosophical Publishing Company. 1906.

Pistorius PV. Plotinus and Neoplatonism: An Introduction. Cambridge: Bowes and Bowes. 1952.

Plotinus.The Enneads (trans MacKenna S, Page BS). Chicago. William Benton Pub. 1952.

Plato. Timaeus. C360 BCE. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1572/1572-h/1572-h.htm

Schoedel, W. “Gnostic Monism and the Gospel of Truth” in The Rediscovery of Gnosticism, Vol.1: The School of Valentinus. edited by Bentley Layton. E.J.Brill. Leiden. 1980.

Iamblichus. Taylor T (trans.). Life of Pythagoras. Inner Traditions. Vermont. 1986.

Thomassen, E. “Gnostics and Orphics” in Myths, Martyrs, and Modernity: Studies in the History of Religions in Honour of Jan Bremmer, ed. J. Dijkstra, J. Kroesen, Y. Kuiper. 2010. https://www.academia.edu/9281118/Orphics_and_Gnostics_2010

Tremlin T. Minds and Gods: the Cognitive Foundations of Religion. Oxford. 2006.

Vitale C. Why Plotinus Matters Today: Plotinus as Dynamic Set Theorist of the Virtual. 2012. https://networkologies.wordpress.com/2012/01/01/the-philosophy-of-the-future-plotinus-as-dynamic-set-theorist-of-the-virtual-realy/

Wallis RT (Ed.). Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. SUNY 1992.

Welburn A. The Beginnings of Christianity. Floris. 2004.

Whittaker T. Transcendence in Spinoza. Mind, 38(151), 293-311. 1929. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2249972

Article by: Matt D.A. Fletcher

Matt DA Fletcher is the Sovereign Grand Master of the Allied Masonic Degrees of Canada; the Director-General of Studies of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia as well as Chief Adept for the SRIA Province of British Columbia & Yukon; is a past Grand Superintendent of the Supreme Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons of British Columbia & Yukon; and is or has been a member of almost every regular masonic body in current existence.

Initiated into the Three Pillars Lodge No.4923 in London, and a mason for almost 30 years, he is a subscribing member of bodies in the UK, Canada, the US, Brazil, Belgium & France. He also holds senior positions in a number of Martinist orders and bodies, and is deeply involved in the esoteric avenues beyond regular Freemasonry.

His primary objective is to increase the academic content within Freemasonry, such that we can practically expand and apply the knowledge that we learn in the Craft, and engage with and assist our Brethren more fully on their own personal masonic journey.

In the mundane world, he is a practising orthopaedic surgeon in rural Canada with a strong background in surgical research, and has published and presented over 350 academic and esoteric papers, chapters, and books.

Recent Articles: Esoteric series

Unveil the secrets of Pansophic Freemasonry, a transformative journey through the ancient mystical traditions. Delve into the sacred realms of Rosicrucianism, Templar wisdom, Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and more. Discover the Graal, the sacred Grail that connects all esoteric paths. Embrace a holistic spiritual quest that reveals the profound mysteries of self and the universe. |

Dive into a spiritual journey where self-awareness is the key to enlightenment. The Gospel of Thomas and Masonic teachings converge on the profound truth that the path to transcendent wisdom lies within us. Embrace a diversified understanding of spirituality, emphasizing introspection as the gateway to a universally respected enlightenment. Explore, understand, transcend. |

Philosophy the Science of Estimating Values Philosophy is the science of estimating values. The superiority of any state or substance over another is determined by philosophy. By assigning a position of primary importance to what remains when all that is secondary has been removed, philosophy thus becomes the true index of priority or emphasis in the realm of speculative thought. The mission of philosophy a priori is to establish the relation of manifested things to their invisible ultimate cause or nature. |

Unlocking the Mysteries: The Surprising Connection Between Freemasonry and Astrologers Revealed! Delve into the intriguing world of Freemasonry and explore its ties to astrological practices. Discover how these two distinct realms intersect, offering a fascinating glimpse into the esoteric interests of some Freemasons. Uncover the hidden links and unravel the enigmatic bond between Freemasonry and astrologers! |

Neoplatonism, a philosophy with profound influence from the 3rd to the 6th century, merges Platonic ideals with Eastern thought, shaping Western and Middle-Eastern philosophy for two millennia. It emphasizes the unity of the individual with the supreme 'One', blending philosophy with theology and impacting major religious and philosophical movements, including Christianity and Islam. |

The enigmatic allure of Freemasonry's ancient rituals and Gnosticism's search for hidden knowledge capture the human spirit's endless quest for enlightenment. Between the stonemason's square and the Gnostic's divine spark lies a tantalizing intersection of philosophy, spirituality, and the pursuit of esoteric wisdom. Both traditions beckon with the promise of deeper understanding and moral elevation, inviting those who are drawn to unravel the tapestries of symbols and allegories. Whether through the fellowship of the lodge or the introspective journey of the soul, the paths of Freemasonry and Gnosticism represent a yearning to connect with something greater than ourselves—an impulse as old as time and as compelling as the mysteries they guard. |

Embark on a journey through time and spirituality with our in-depth exploration of the Theosophical Society's Seal. This ancient emblem, rich with symbols, bridges humanity with the cosmos, echoing through the world's great faiths and diverse cultures. Our paper delves into the six mystical symbols, untangling their profound meanings and tracing their presence in historic art worldwide. Unaffiliated with worldly movements, these symbols open a window to esoteric wisdom. We also probe potential parallels with Freemasonry, seeking threads that might connect these storied organizations. Join us in unveiling the universal language of the spirit encoded within this enigmatic Seal. |

Discover the pathway to divine oneness through the concept of self-dominance. This thought-provoking essay explores the profound connection between self-control, spiritual growth, and achieving unity with the divine essence. With an interdisciplinary approach, it offers practical steps towards expanding consciousness and deepening our understanding of the divine. |

The Winding Staircase and its Kabbalistic Path The Winding Staircase in freemasonry is a renowned symbol of enlightenment. In this article, we explore its connection to Kabbalistic thought and how it mirrors the inner growth of a candidate as he progresses throughout his Masonic journey. From faith and discipline in Binah, to strength and discernment in Geburah, and finally to victory and emotional intuition in Netzach, each step represents a crucial aspect of personal development. Join us as we delve into the esoteric meanings of this powerful symbol. |

Unravel the mystic origins of Capitular Masonry, a secretive Freemasonry branch. Explore its evolution, symbolic degrees, and the Royal Arch's mysteries. Discover the Keystone's significance in this enlightening journey through Masonic wisdom, culminating in the ethereal Holy Royal Arch. |

Reflections on the Second Degree Work Bro. Draško Miletić offers his reflections on his Second Degree Work – using metaphor, allegory and symbolism to understand the challenges we face as a Fellow Craft Mason to perfect the rough ashlar. |

Diversity and Universality of Masonic Work Explore the rich tapestry of Masonic work, a testament to diversity and universality. Uncover its evolution through the 18th century, from the stabilization of Symbolic Freemasonry to the advent of Scottish rite and the birth of Great Continental Rites. Dive into this fascinating journey of Masonic systems, a unique blend of tradition and innovation. Antonio Jorge explores the diversity and universality of Masonic Work |

Nonsense as a Factor in Soul Growth Although written 100 years ago, this article on retaining humour as a means of self-development and soul growth is as pertinent today as it was then! Let us remember the words of an ancient philosopher who said, when referring to the court jester of a king, “It takes the brightest man in all the land to make the greatest fool.” |

Freemasonry: The Robe of Blue and Gold Three Fates weave this living garment and man himself is the creator of his fates. The triple thread of thought, action, and desire binds him when he enters into the sacred place or seeks admittance to the Lodge, but later this same cord is woven into the wedding garment whose purified folds shroud the sacred spark of his being. - Manly P Hall |

By such a prudent and well regulated course of discipline as may best conduce to the preservation of your corporal and metal faculties in the fullest energy, thereby enabling you to exercise those talents wherewith god has blessed you to his glory and the welfare of your fellow creatures. |

Jacob Ernst's 1870 treatise on the Philosophy of Freemasonry - The theory of Freemasonry is based upon the practice of virtuous principles, inculcating the highest standard of moral excellence. |

Alchemy, like Freemasonry, has two aspects, material and spiritual; the lower aspect being looked upon by initiates as symbolic of the higher. “Gold” is used as a symbol of perfection and the earlier traces of Alchemy are philosophical. A Lecture read before the Albert Edward Rose Croix Chapter No. 87 in 1949. by Ill. Bro. S. H. Perry 32° |

The spirit of the Renaissance is long gone and today's globalized and hesitant man, no matter ideology and confession, is the one that is deprived of resoluteness, of decision making, the one whose opinion doesn't matter. Article by Draško Miletić, |

A Mason's Work in the First Degree Every Mason's experiences are unique - here writer and artist Draško Miletić shares insights from his First Degree Work. |

Initiation and the Lucis Trust The approach of the Lucis Trust to initiation may differ slightly to other Western Esoteric systems and Freemasonry, but the foundation of training for the neophyte to build good moral character and act in useful service to humanity is universal. |

Who were the mysterious 18th century Élus Coëns – a.k.a The Order of Knight-Masons Elect Priests of the Universe – and why did they influence so many other esoteric and para-Masonic Orders? |

Bro. Chris Hatton gives us his personal reflections on the history of the 'house at Blackheath and the Blackheath Orders', in this wonderful tribute to Andrew Stephenson, a remarkable man and Mason. |

Book Review - Cagliostro the Unknown Master The book review of the Cagliostro the Unknown Master, by the Editor of the book |

We explore fascinating and somewhat contentious historical interpretations that Freemasonry originated in ancient Egypt. |

Is Freemasonry esoteric? Yes, no, maybe! |

Egyptian Freemasonry, founder Cagliostro was famed throughout eighteenth century Europe for his reputation as a healer and alchemist |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device