Philosophy is the science of estimating values. The superiority of any state or substance over another is determined by philosophy.

By assigning a position of primary importance to what remains when all that is secondary has been removed, philosophy thus becomes the true index of priority or emphasis in the realm of speculative thought.

The mission of philosophy a priori is to establish the relation of manifested things to their invisible ultimate cause or nature.

Welcome to the fascinating world of ancient philosophy. As you embark on this intellectual journey, you might come across complex texts that seem daunting.

But fear not! Let’s break down the meaning of the passage you’ve provided in a way that’s both engaging and easy to understand.

What is Philosophy?

The text begins with a bold statement: “PHILOSOPHY is the science of estimating values.” At its core, philosophy seeks to understand the value and importance of things.

Think of it like this: if life was a vast marketplace, philosophy would be the appraiser, determining the worth of each item.

The Hierarchy of Importance

The passage mentions the “superiority of any state or substance over another.” This is a fancy way of saying that philosophy helps us rank things in order of importance.

For instance, in your daily life, you might prioritize family over a video game or health over indulgence. Philosophy dives deep into these choices, exploring why we value one thing over another.

Stripping Away the Unnecessary

The text talks about assigning primary importance to what remains after removing the secondary. Imagine you’re sculpting a statue out of marble.

You start with a big block and chip away everything that doesn’t look like the figure you have in mind. Similarly, philosophy helps us remove unnecessary distractions and focus on what truly matters.

Philosophy as a Guide

The passage describes philosophy as “the true index of priority or emphasis in the realm of speculative thought.”

This means that philosophy acts as a compass, guiding us through the vast ocean of ideas and theories. It helps us determine which ideas are worth exploring further and which can be set aside.

The Ultimate Quest

Lastly, the text touches upon the grand mission of philosophy: “to establish the relation of manifested things to their invisible ultimate cause or nature.” This is the heart of many philosophical inquiries.

It’s about understanding the deeper, often hidden, reasons behind why things are the way they are. It’s like asking, “Why is the sky blue?” and then diving into layers of explanations about the atmosphere, light, and human perception.

Conclusion

In essence, the passage you’ve shared captures the spirit of philosophy. It’s a discipline that encourages us to question, evaluate, and seek deeper understanding.

As you continue your studies, remember that philosophy isn’t just about reading old texts; it’s a way of engaging with the world, questioning assumptions, and seeking truth. Welcome to the adventure!

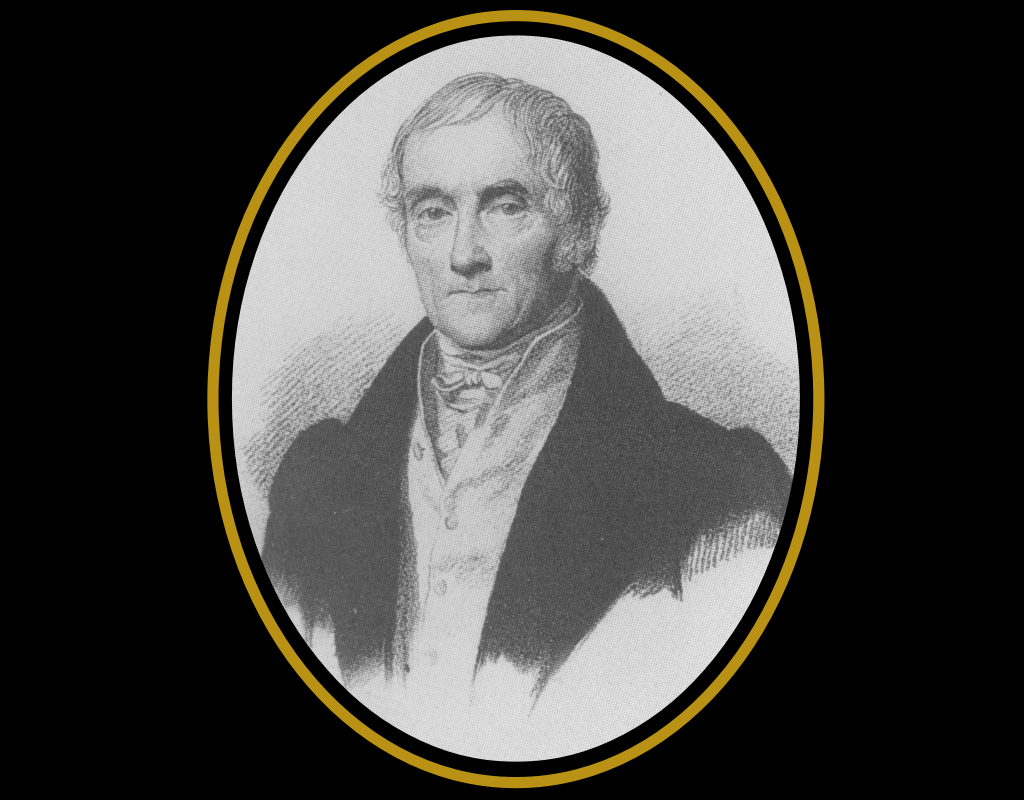

Sir William Hamilton

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

“Philosophy,” writes Sir William Hamilton, “has been defined [as]:

The science of things divine and human, and of the causes in which they are contained [Cicero];

The science of effects by their causes [Hobbes];

The science of sufficient reasons [Leibnitz];

The science of things possible, inasmuch as they are possible [Wolf];

The science of things evidently deduced from first principles [Descartes];

The science of truths, sensible and abstract [de Condillac];

The application of reason to its legitimate objects [Tennemann];

The science of the relations of all knowledge to the necessary ends of human reason [Kant];

The science of the original form of the ego or mental self [Krug];

The science of sciences [Fichte];

The science of the absolute [von Schelling];

The science of the absolute indifference of the ideal and real [von Schelling]–or,

The identity of identity and non-identity [Hegel].”

(See Lectures on Metaphysics and Logic.)

Decoding Philosophical Definitions: A Deep Dive into Varied Perspectives

This article offers a myriad of definitions for the term “philosophy” from various renowned philosophers. Each definition reflects the unique perspective and focus of its author. Let’s unpack these definitions one by one, making them accessible for a budding philosopher.

Marcus Tullius Cicero

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Cicero: The All-Encompassing Science

Cicero defines philosophy as “The science of things divine and human, and of the causes in which they are contained.” This broad definition encompasses both the spiritual (divine) and the worldly (human), emphasizing philosophy’s role in understanding the underlying causes of both realms.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, a prominent statesman, orator, and philosopher of the late Roman Republic, provided a holistic definition of philosophy as “The science of things divine and human, and of the causes in which they are contained.” To truly grasp the depth of this statement, we must delve into Cicero’s life, his philosophical influences, and the broader context of his times.

Cicero: The Man Behind the Philosophy

Born in 106 BCE and murdered in 43 BCE, Cicero’s life coincided with the decline and fall of the Roman Republic. He was not only a leading political actor of his era but also a prolific writer. His writings serve as a valuable source of information about the political and philosophical landscape of ancient Rome.

Philosophical Influences

Cicero’s philosophical education was diverse. He studied under the Epicurean Phaedrus, the Stoic Diodotus, and the Academic Philo of Larissa. This exposure to multiple schools of thought provided him with a comprehensive grounding in philosophy.

The Dual Realms of Divine and Human

Cicero’s definition captures the essence of philosophy’s quest to understand both the spiritual and the worldly.

The “divine” refers to matters of the gods, spirituality, and the metaphysical. In contrast, the “human” pertains to worldly affairs, human nature, and societal constructs.

The Quest for Causes

By emphasizing “the causes in which they are contained,” Cicero underscores philosophy’s role in probing the underlying reasons or principles governing both the divine and human realms.

This search for causes aligns with the broader philosophical tradition of seeking explanations for observed phenomena.

Relevance in Modern Times

Cicero’s holistic approach to philosophy resonates even today. In an era marked by specialization, his definition reminds us of the interconnectedness of various domains of knowledge and the importance of understanding the broader context.

Conclusion

Cicero’s definition of philosophy is both profound and encompassing. It serves as a testament to his diverse philosophical education and his keen observations of the world around him.

As we navigate the complexities of modern life, Cicero’s words offer timeless wisdom, urging us to seek understanding in both the spiritual and worldly realms.

Thomas Hobbes

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Hobbes and the Philosophy of Cause and Effect

For Hobbes, philosophy is “The science of effects by their causes.” This definition highlights the cause-and-effect relationship, suggesting that philosophy seeks to understand the reasons behind various outcomes.

Thomas Hobbes, a prominent 17th-century English philosopher, is best known for his political thought, especially as articulated in his magnum opus, “Leviathan.” However, his views on cause and effect, as highlighted in the definition “The science of effects by their causes,” offer a deep insight into his broader philosophical framework.

Hobbes’s Mechanistic Worldview

Hobbes’s philosophy is rooted in a mechanistic and materialist psychology. He believed that all phenomena in the universe can be explained in terms of the motions and interactions of material bodies. This perspective naturally leads to a focus on cause and effect, as understanding the motion and interaction of objects requires identifying the causes behind their effects.

The Essence of Philosophical Inquiry

For Hobbes, the quest for causes is the essence of all philosophical inquiry. He posited that philosophy provides knowledge of effects or appearances acquired through true ratiocination (logical reasoning) from the knowledge of their causes or generation.

The Role of Causality in Hobbes’s Political Philosophy

Hobbes’s political philosophy, especially his social contract theory, can also be understood through the lens of cause and effect. In “Leviathan,” Hobbes explores the causes of social unrest and the effects of different forms of governance.

He argues that in the state of nature, where there is no authority, individuals act based on their self-interest, leading to a “war of all against all.”

The effect of this chaotic state is the need for a strong central authority to maintain order, which is the Leviathan.

Hobbes and Aristotelian Causality

While Hobbes’s views on causality were groundbreaking in many ways, they also had roots in earlier philosophical traditions. Hobbes’s theory of causality has been compared to Aristotelian concepts of cause and effect, although Hobbes’s mechanistic approach was a departure from Aristotle’s more teleological perspective.

The Broader Implications of Hobbes’s Causality

Beyond politics and psychology, Hobbes’s emphasis on cause and effect had implications for his views on science, metaphysics, and epistemology. He believed in the importance of defining concepts necessary for fruitful inquiries concerning natural bodies, such as body, motion, time, place, cause, and effect.

Conclusion

Thomas Hobbes’s definition of philosophy as “The science of effects by their causes” is a testament to his belief in the primacy of cause and effect in understanding the world.

Whether discussing the nature of human behavior, the dynamics of political power, or the intricacies of the natural world, Hobbes consistently sought to identify the underlying causes behind observable effects.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Leibnitz and the Principle of Sufficient Reason

Leibnitz describes philosophy as “The science of sufficient reasons.” This means philosophy aims to find satisfactory explanations or justifications for phenomena.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent philosopher of the 17th and 18th centuries, introduced a foundational concept in philosophy known as the “Principle of Sufficient Reason” (PSR). This principle has been a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry, emphasizing the necessity for explanations or justifications for phenomena.

The Principle Explained

The Principle of Sufficient Reason can be summarized as follows: For every entity or event, if it exists or occurs, there must be a sufficient explanation for its existence or occurrence. In simpler terms, everything that exists or happens has a reason behind it, and it’s the job of philosophy (and other disciplines) to uncover these reasons.

Why Did Leibniz Believe in the PSR?

Leibniz’s belief in the PSR was rooted in his broader philosophical views. He posited that the universe operates in a rational and orderly manner. Thus, every event or entity, no matter how trivial or significant, must have an underlying cause or reason.

This belief was not just a mere assumption; for Leibniz, it was a fundamental truth about the nature of reality.

Applications of the PSR

The PSR has been applied in various philosophical contexts. For instance, in metaphysics, it has been used to argue for the existence of God as the ultimate reason for the universe. In epistemology, it underscores the importance of rational justification for our beliefs.

Contemporary Relevance

While the PSR has its roots in ancient and medieval philosophy, it remains relevant in contemporary philosophical discussions. Modern philosophers have debated its implications, scope, and validity, especially in the context of causality, determinism, and the nature of explanation.

Conclusion

Leibniz’s Principle of Sufficient Reason is more than just a philosophical concept; it’s a lens through which we can view the world. It challenges us to seek explanations, to be curious, and to strive for understanding.

As you delve deeper into philosophy, you’ll find that principles like the PSR provide a foundation upon which many philosophical arguments and inquiries are built.

Christian Wolff

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Wolf and the Philosophy of Possibilities

Wolf defines philosophy as “The science of things possible, inasmuch as they are possible.” Here, the focus is on understanding the nature of possibilities and their limits.

Christian Wolff (1679-1754) was a prominent figure of the German Enlightenment, known for his contributions to philosophy, mathematics, and science.

His definition of philosophy as “The science of things possible, inasmuch as they are possible” offers a unique perspective on the discipline. Let’s delve deeper into this definition and its implications.

Christian Wolff: A Brief Overview

Wolff is often considered a bridge between the philosophies of Leibniz and Kant. He played a pivotal role in shaping German philosophical thought during the Enlightenment era. His works often sought to systematize philosophical knowledge, emphasizing clarity and precision.

The Nature of Possibilities

Wolff’s definition focuses on the exploration of what is possible. In philosophy, possibilities pertain to potential realities or states of affairs. For Wolff, philosophy’s task is to understand these potential realities in their fullest extent, examining their nature and the boundaries that define them.

The Interplay of Existence and Possibility

Wolff’s ontology, or study of being, often revolved around the relationship between existence and possibility. He believed that for something to exist, it must first be possible. Thus, understanding the realm of possibilities is crucial for grasping the nature of existence.

Philosophy as a Systematic Endeavor

Wolff’s approach to philosophy was systematic. He believed in organizing knowledge in a coherent and structured manner. This systematic approach can be seen in his definition, where he emphasizes understanding possibilities in a comprehensive way, leaving no stone unturned.

Implications for Modern Thought

While Wolff’s definition might seem abstract, it has profound implications for modern philosophical inquiries. By focusing on possibilities, we are encouraged to think beyond the present, to imagine alternative realities, and to question the limits of what we know.

This perspective is particularly relevant in areas like modal logic, which deals with notions of possibility and necessity.

Conclusion

Christian Wolff’s definition of philosophy offers a unique lens through which we can view the discipline. By emphasizing the exploration of possibilities, Wolff encourages us to think broadly, question deeply, and imagine freely.

As you continue your philosophical journey, consider the vast realm of possibilities that await exploration.

René Descartes

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Descartes and Deductive Reasoning: A Deeper Exploration

Descartes views philosophy as “The science of things evidently deduced from first principles.” This emphasizes the deductive method, where conclusions are drawn from established truths or principles.

René Descartes, a 17th-century French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist, is often referred to as the “Father of Modern Philosophy.” His approach to philosophy was groundbreaking, emphasizing the importance of deductive reasoning. Let’s delve deeper into Descartes’ perspective on deductive reasoning and its significance in his philosophical framework.

The Cartesian Method

Descartes is renowned for his methodological approach to philosophy. According to the [Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy], Descartes recognized two primary sources of knowledge: intuition and deduction. This method was rooted in the belief that true knowledge could be attained by starting with self-evident truths or “first principles” and then deducing other truths from them.

Rejecting the Syllogism

An interesting aspect of Descartes’ approach is his rejection of the syllogistic logic that was prevalent in his time. As noted by [Oxford Academic], Descartes believed that while syllogistic logic could sharpen young students’ wits, it was largely ineffective for discovering new truths. Instead, he championed a method that emphasized clear and distinct ideas as the foundation for knowledge.

“I Think, Therefore I Am”

One of Descartes’ most famous statements is “Cogito, ergo sum” or “I think, therefore I am.” This statement is a testament to his belief in the power of deductive reasoning. For Descartes, the very act of doubting one’s existence paradoxically confirmed it. This self-awareness became the foundational “first principle” from which other truths could be deduced.

Deductive Reasoning vs. Inductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning, as described by [Wikipedia], is the process of drawing conclusions from established premises. It contrasts with inductive reasoning, where general conclusions are drawn from specific observations. Descartes’ emphasis on deduction was rooted in the belief that starting with clear and undeniable truths would lead to certain knowledge.

The Legacy of Descartes’ Deductive Method

Descartes’ emphasis on deductive reasoning has left an indelible mark on the field of philosophy.

His method of starting with self-evident truths and building upon them has influenced countless philosophers and thinkers. Moreover, his approach laid the groundwork for the scientific method, emphasizing the importance of systematic observation, hypothesis formation, and logical deduction.

Conclusion

René Descartes’ emphasis on deductive reasoning reshaped the landscape of philosophy. By championing a method that prioritized clear and distinct ideas, Descartes provided a robust framework for knowledge acquisition.

His legacy serves as a testament to the enduring power of logical deduction and its role in the quest for truth.

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

de Condillac: Truths, Both Tangible and Intangible

For de Condillac, philosophy is “The science of truths, sensible and abstract.” This definition acknowledges both tangible truths (sensible) and conceptual truths (abstract).

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, a prominent figure of the Enlightenment era, offered a unique perspective on the nature of knowledge and truth. His definition of philosophy as “The science of truths, sensible and abstract” provides a dual lens through which we can understand the world.

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac was a French philosopher who lived during the 18th century. He is best known for his empiricist views, which emphasized the role of experience in shaping human knowledge.

His philosophy was deeply influenced by John Locke, the English philosopher who championed the idea that our minds are blank slates, filled by experiences.

Sensible Truths: The Tangible

When de Condillac speaks of “sensible” truths, he refers to knowledge derived from our senses. This encompasses everything we can see, touch, hear, taste, and smell. For instance, the fact that the sky is blue or that fire is hot are sensible truths. They are immediate, tangible, and can be directly experienced.

Abstract Truths: The Conceptual

On the other hand, “abstract” truths are not directly tied to sensory experience. Instead, they are conceptual, often derived from reasoning and reflection. Examples include mathematical truths, moral principles, or philosophical concepts. These truths are not always directly observable but are crucial for understanding complex ideas and theories.

Sensationism: de Condillac’s Key Philosophy

One of de Condillac’s most significant contributions to philosophy is his theory of “sensationism.” This theory posits that all our knowledge originates from sensory experiences.

In his work “Treatise on Sensations,” de Condillac conducts a thought experiment involving a statue. He imagines giving this statue senses one by one, demonstrating how each new sense contributes to its understanding of the world.

The Role of Language

In addition to his views on sensation, de Condillac emphasized the importance of language in logical reasoning. He believed that a scientifically designed language, grounded in mathematical calculation, was essential for clear and precise thought.

Conclusion

de Condillac’s definition of philosophy underscores the importance of both direct experience and abstract reasoning in our quest for knowledge.

By acknowledging both sensible and abstract truths, he provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the world around us and the ideas that shape it.

Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Tennemann: The Application of Reason

Tennemann describes philosophy as “The application of reason to its legitimate objects.” This definition underscores the use of rational thinking in understanding various subjects.

Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann, a German historian of philosophy, offers a unique perspective on the essence of philosophy.

He describes it as “The application of reason to its legitimate objects.” To understand this definition more deeply, let’s delve into Tennemann’s background and the broader context of his philosophical views.

Who was Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann?

Tennemann (1761-1819) was a German historian of philosophy. He was educated at Erfurt and later became a lecturer on the history of philosophy at the University of Jena. Eventually, he ascended to a professorial position at the same university.

His contributions to philosophy were significant, and he is remembered for his works that spanned various philosophical topics and historical contexts.

The Essence of Tennemann’s Definition

When Tennemann speaks of the “application of reason,” he is referring to the use of logical and rational thinking.

Reason, in philosophy, is often seen as the tool by which we understand, analyze, and make judgments about the world around us. It’s our capacity to think logically, make connections, and derive conclusions.

The term “legitimate objects” suggests that there are appropriate and inappropriate subjects for reason to tackle. In other words, while reason is a powerful tool, it has its boundaries. There are areas where it can be applied effectively and others where it might not be the most suitable method of understanding.

Contextualizing Tennemann’s Definition

Tennemann’s definition can be seen as a response to the broader philosophical debates of his time. The Enlightenment era, which preceded Tennemann’s lifetime, emphasized reason as the primary source of authority and knowledge, challenging traditional sources like faith or tradition.

Tennemann’s definition aligns with this Enlightenment ideal, emphasizing the importance of reason in philosophical inquiry.

The Broader Implications

Tennemann’s perspective underscores the importance of using reason judiciously. While reason is a powerful tool for understanding various subjects, it’s essential to recognize its limits.

Not all subjects may be fully comprehensible through reason alone, and there might be areas where other forms of understanding, such as intuition or emotion, play a crucial role.

Conclusion

Tennemann’s definition of philosophy as the application of reason to its legitimate objects offers a nuanced perspective on the role of rational thinking in philosophical inquiry. It reminds us of the power and limits of reason and encourages us to use it wisely in our quest for knowledge.

Immanuel Kant

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Kant: Knowledge and Human Reason – An Expanded Exploration

Kant defines philosophy as “The science of the relations of all knowledge to the necessary ends of human reason.” This highlights the relationship between knowledge and the ultimate goals or purposes of human rationality.

Immanuel Kant, an 18th-century German philosopher, is renowned for his profound contributions to epistemology (the study of knowledge) and metaphysics. His definition of philosophy as “The science of the relations of all knowledge to the necessary ends of human reason” offers a deep insight into his philosophical approach. Let’s delve deeper into this definition and its implications.

The Role of Reason in Knowledge

According to the [Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy], reason plays a pivotal role in Kant’s account of knowledge.

In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” Kant explores how human reason interacts with knowledge, emphasizing that reason is not just a passive recipient of information but actively structures our understanding of the world.

The Ends of Human Reason

A discussion on [Philosophy Stack Exchange] raises an intriguing point: while it might seem that knowledge is the primary goal of human reason, Kant’s definition suggests that there are other “ends” or purposes to which reason aspires.

This could mean that while acquiring knowledge is essential, how we use that knowledge and to what purpose is equally crucial.

Human Understanding and the Moral Law

Kant believed that human understanding provides the general laws of nature that structure our experiences.

Furthermore, he posited that human reason gives itself the moral law, which forms our basis for belief in concepts like God, freedom, and immortality, as mentioned in the [Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy].

Transcendental Idealism

Central to Kant’s philosophy is the doctrine of “transcendental idealism.” This doctrine emphasizes a distinction between what we can experience (the observable world) and what we cannot, such as “supersensible” objects like God and the soul. Kant argued that true knowledge is only possible about things we can experience, as highlighted in the [Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy].

The Critique of Pure Reason

In his seminal work, the “Critique of Pure Reason,” Kant sought to understand the limits and capacities of human reason. He believed that while reason has immense capabilities, it also has boundaries that should be recognized. This critique was not meant to diminish the value of reason but to provide a clearer understanding of its role in the acquisition of knowledge.

Autonomy and Human Reason

Kant is often described as the philosopher of human autonomy. He believed that through reason, humans can discover and adhere to the fundamental principles of knowledge and action without external intervention, especially divine support. This perspective underscores the power and independence of human reason, as noted in the [Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy].

Conclusion

Kant’s definition of philosophy underscores the intricate relationship between knowledge and the purposes of human reason.

For Kant, philosophy is not just about acquiring knowledge but understanding its relation to the broader objectives of human rationality.

As you delve deeper into Kant’s works and ideas, you’ll discover a rich tapestry of thoughts on the nature of knowledge, reason, and human existence.

Wilhelm Traugott Krug

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Krug’s Philosophy: A Deep Dive into the Ego and Mental Self

For Krug, philosophy is “The science of the original form of the ego or mental self.” This definition delves into self-awareness and understanding one’s intrinsic nature.

Wilhelm Traugott Krug, a German philosopher, had a unique perspective on the concept of the self, particularly focusing on the “ego” or “mental self.” Let’s delve deeper into Krug’s philosophy and its implications for self-awareness and understanding one’s intrinsic nature.

Krug and the Kantian School

Krug is considered to be part of the Kantian School of logic, which emphasizes the importance of reason and the human capacity for judgment. This school of thought, influenced by the renowned philosopher Immanuel Kant, often grapples with the nature of the self and consciousness. [Wilhelm Traugott Krug – Wikipedia].

The Ego and Reflection

Krug’s method in philosophy was psychological. He sought to explain the Ego by examining how it reflects upon the facts of consciousness.

In other words, Krug was interested in how our sense of self (the Ego) interprets and understands our own thoughts, feelings, and experiences. This reflection is central to our self-awareness and understanding of our intrinsic nature.

The Ego in Broader Philosophical Context

The concept of the ego is not unique to Krug. It has been a subject of interest in both philosophy and psychology for centuries.

The ego is often understood as the part of the psyche that provides continuity and consistency to behavior.

It acts as a personal point of reference, connecting past memories with present actions and future anticipations. [Ego | Definition & Facts | Britannica].

The Ego and Self-Knowledge

In philosophy, self-knowledge refers to knowledge of one’s own mental states. This includes understanding what one feels, thinks, believes, or desires. Krug’s focus on the ego aligns with this broader philosophical pursuit of self-knowledge, as the ego is central to how we perceive and understand our own mental states. [Self-Knowledge – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy].

Conclusion

Krug’s exploration of the ego offers a profound insight into the nature of self-awareness and the human psyche.

By understanding the ego’s role in reflecting upon our consciousness, we can better grasp our own identities and the intrinsic nature that defines us.

As you continue your philosophical journey, consider how Krug’s perspective on the ego resonates with your own understanding of self and consciousness.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Fichte: Philosophy as “The Science of Sciences”

Fichte describes philosophy as “The science of sciences.” This grand definition places philosophy at the pinnacle of all intellectual pursuits.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a prominent figure in German philosophy, described philosophy as “The science of sciences.” This definition, while concise, carries profound implications about the nature and role of philosophy.

Let’s delve deeper into Fichte’s perspective and understand why he placed philosophy at the zenith of intellectual endeavors.

Fichte’s Philosophical Landscape

Fichte is often recognized as one of the major figures in German philosophy, particularly in the period between Kant and Hegel. He developed his own system of transcendental philosophy, known as the Wissenschaftslehre, which can be translated as the “Science of Knowledge” or “Doctrine of Science.”

The Wissenschaftslehre: A Deep Dive

The Wissenschaftslehre, Fichte’s magnum opus, is a multilevel deduction from the unity of his philosophical system. At its core, it explores the conditions of consciousness, emphasizing self-consciousness, practical subjectivity, and more.

This work reflects Fichte’s belief in philosophy as an overarching discipline that provides a foundation for all other sciences.

Philosophy: Beyond Empirical Sciences

For Fichte, transcendental philosophy, or the Wissenschaftslehre, stands in contrast to the empirical sciences. It offers a perspective that goes beyond the standpoint of everyday life, ordinary consciousness, or common sense.

While empirical sciences focus on observable phenomena, philosophy delves into the underlying principles and foundational truths.

The Ultimate Foundation of Knowledge

Fichte’s emphasis on philosophy as the “science of sciences” suggests that all other disciplines, whether natural or social sciences, derive their principles and foundational concepts from philosophy.

In other words, if human knowledge were to form a cohesive system, all principles would ultimately rest on a single foundational science, which Fichte refers to as the “science of science as such.

Philosophy as an Enacted Truth

Fichte believed that philosophy is something we enact rather than a mere set of propositions. Philosophical truths, for Fichte, are spontaneous inward realizations rather than externally expressible facts.

This perspective further elevates philosophy, making it not just a discipline of thought, but a way of being and understanding.

Conclusion

Fichte’s definition of philosophy as “The science of sciences” is not just a grand statement but a reflection of his deep-seated belief in philosophy’s foundational role in all intellectual pursuits.

Through his works, especially the Wissenschaftslehre, Fichte showcased how philosophy provides the bedrock upon which all other sciences stand, making it truly the ultimate science.

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

von Schelling’s Philosophy of the Absolute: A Deeper Exploration

von Schelling offers two definitions. The first is “The science of the absolute,” emphasizing the study of unchanging truths. The second is “The science of the absolute indifference of the ideal and real,” which delves into the convergence of ideas and reality.

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, a prominent figure in the German Idealist tradition alongside J.G. Fichte and G.W.F. Hegel, offers profound insights into the nature of the Absolute. Let’s delve deeper into his two definitions, drawing from reputable sources to provide a comprehensive understanding.

The Science of the Absolute

Schelling’s first definition, “The science of the absolute,” revolves around the study of unchanging truths. In the realm of German Idealism, the Absolute is often perceived as an all-encompassing reality or truth that remains constant irrespective of individual perceptions or interpretations.

Reference: [Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on Schelling]

The Convergence of the Ideal and the Real

Schelling’s second definition, “The science of the absolute indifference of the ideal and real,” is particularly intriguing. It suggests a synthesis or merging point where ideas (the ideal) and tangible reality (the real) converge. This convergence implies that there’s an underlying unity or sameness between our conceptual understandings and the external world.

The term “absolute indifference” is crucial here. It doesn’t mean apathy or lack of interest. Instead, it signifies a state where distinctions between the ideal and real dissolve, pointing towards a deeper, unified reality.

Reference: [Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy on F. W. J. von Schelling]

Absolute Idealism: A Broader Context

Schelling’s philosophy can be situated within the broader framework of Absolute Idealism. This philosophical theory, associated with both Schelling and Hegel, posits that reality is a manifestation of an absolute or ultimate spirit. This spirit, or the Absolute, is both the source and culmination of all existence, encompassing both the ideal and the real.

Reference: [Britannica on Absolute Idealism]

Conclusion

Schelling’s exploration of the Absolute offers a profound perspective on the relationship between thought and reality.

By suggesting a point of convergence between the ideal and real, he challenges us to reconsider the boundaries of knowledge and existence.

As you delve deeper into philosophical studies, Schelling’s insights provide a rich tapestry of ideas, encouraging a holistic understanding of the world around us.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Hegel on Identity: A Deeper Dive

Hegel’s definition, “The identity of identity and non-identity,” is a bit complex. It speaks to the idea that things can be both similar (identity) and different (non-identity) simultaneously, reflecting Hegel’s dialectical method.

The article from Emory University’s “Basic Problems of Philosophy” course delves into Hegel’s views on identity as presented in his work, “Phenomenology of Spirit.” Hegel’s perspective on identity is intricate and challenges conventional notions of self-awareness and the nature of things.

Sense-Certainty and Self-Consciousness

Hegel introduces the concept of “sense-certainty” as the genuine feeling derived from sensory experiences.

In his perspective, this form of certainty seems to be the most truthful way of gaining information since it offers the most truth to an individual. However, Hegel critiques this notion, suggesting that such certainty makes it challenging to discern deviations from this established truth.

He further posits that in this certainty, consciousness exists only as a “pure I,” implying that the purest form of self-awareness is self-consciousness. By understanding oneself, one can attribute qualities to oneself and, by extension, to the external world.

The Nature of Things and Relativity

Hegel makes a profound statement: “the thing is, and it is merely because it is.” While this might seem oversimplified, it underscores the idea that objects possess inherent qualities, and the reason for their existence is inconsequential.

He further explores the relativity of qualities through a thought experiment. If one were to note that it’s nighttime and revisit this observation at noon, the truth of the statement would change based on the time and location.

This experiment illustrates that qualities are not universally constant; they can vary based on perspectives. Thus, what one person perceives as a quality might differ from another person’s viewpoint, introducing an element of relativism and uncertainty in defining the world’s attributes.

Concluding Thoughts

Hegel’s exploration of identity challenges us to reconsider our understanding of self and the world. He emphasizes the fluidity of qualities and the inherent subjectivity in our perceptions. This perspective invites us to be more open-minded and recognize the multifaceted nature of identity and reality.

Thought-Provoking Insights

The Fluidity of Truth: If truths, such as the time of day, can change based on perspective, what other “truths” might be more fluid than we think?

The Nature of Self: How does our understanding of ourselves influence our perception of the world around us?

Relativity of Qualities: If qualities can vary based on individual perspectives, how can we arrive at a shared understanding of the world?

Conclusion

As evident from these definitions, philosophy is a multifaceted discipline with varied interpretations.

Each philosopher brings their unique lens to the subject, enriching our understanding. As you delve deeper into your studies, you’ll discover that these definitions are just the tip of the iceberg, and the world of philosophy offers endless avenues for exploration. Happy philosophizing!

Article by: Grant Marsed

Grant Marsed was made a mason in a Liberal Grand Lodge which is associated with CLIPSAS.

He is a retired engineer and devotes much of his time to traveling and philosophical writing.

Recent Articles: Esoteric series

Unveil the secrets of Pansophic Freemasonry, a transformative journey through the ancient mystical traditions. Delve into the sacred realms of Rosicrucianism, Templar wisdom, Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and more. Discover the Graal, the sacred Grail that connects all esoteric paths. Embrace a holistic spiritual quest that reveals the profound mysteries of self and the universe. |

Dive into a spiritual journey where self-awareness is the key to enlightenment. The Gospel of Thomas and Masonic teachings converge on the profound truth that the path to transcendent wisdom lies within us. Embrace a diversified understanding of spirituality, emphasizing introspection as the gateway to a universally respected enlightenment. Explore, understand, transcend. |

Philosophy the Science of Estimating Values Philosophy is the science of estimating values. The superiority of any state or substance over another is determined by philosophy. By assigning a position of primary importance to what remains when all that is secondary has been removed, philosophy thus becomes the true index of priority or emphasis in the realm of speculative thought. The mission of philosophy a priori is to establish the relation of manifested things to their invisible ultimate cause or nature. |

Unlocking the Mysteries: The Surprising Connection Between Freemasonry and Astrologers Revealed! Delve into the intriguing world of Freemasonry and explore its ties to astrological practices. Discover how these two distinct realms intersect, offering a fascinating glimpse into the esoteric interests of some Freemasons. Uncover the hidden links and unravel the enigmatic bond between Freemasonry and astrologers! |

Neoplatonism, a philosophy with profound influence from the 3rd to the 6th century, merges Platonic ideals with Eastern thought, shaping Western and Middle-Eastern philosophy for two millennia. It emphasizes the unity of the individual with the supreme 'One', blending philosophy with theology and impacting major religious and philosophical movements, including Christianity and Islam. |

The enigmatic allure of Freemasonry's ancient rituals and Gnosticism's search for hidden knowledge capture the human spirit's endless quest for enlightenment. Between the stonemason's square and the Gnostic's divine spark lies a tantalizing intersection of philosophy, spirituality, and the pursuit of esoteric wisdom. Both traditions beckon with the promise of deeper understanding and moral elevation, inviting those who are drawn to unravel the tapestries of symbols and allegories. Whether through the fellowship of the lodge or the introspective journey of the soul, the paths of Freemasonry and Gnosticism represent a yearning to connect with something greater than ourselves—an impulse as old as time and as compelling as the mysteries they guard. |

Embark on a journey through time and spirituality with our in-depth exploration of the Theosophical Society's Seal. This ancient emblem, rich with symbols, bridges humanity with the cosmos, echoing through the world's great faiths and diverse cultures. Our paper delves into the six mystical symbols, untangling their profound meanings and tracing their presence in historic art worldwide. Unaffiliated with worldly movements, these symbols open a window to esoteric wisdom. We also probe potential parallels with Freemasonry, seeking threads that might connect these storied organizations. Join us in unveiling the universal language of the spirit encoded within this enigmatic Seal. |

Discover the pathway to divine oneness through the concept of self-dominance. This thought-provoking essay explores the profound connection between self-control, spiritual growth, and achieving unity with the divine essence. With an interdisciplinary approach, it offers practical steps towards expanding consciousness and deepening our understanding of the divine. |

The Winding Staircase and its Kabbalistic Path The Winding Staircase in freemasonry is a renowned symbol of enlightenment. In this article, we explore its connection to Kabbalistic thought and how it mirrors the inner growth of a candidate as he progresses throughout his Masonic journey. From faith and discipline in Binah, to strength and discernment in Geburah, and finally to victory and emotional intuition in Netzach, each step represents a crucial aspect of personal development. Join us as we delve into the esoteric meanings of this powerful symbol. |

Unravel the mystic origins of Capitular Masonry, a secretive Freemasonry branch. Explore its evolution, symbolic degrees, and the Royal Arch's mysteries. Discover the Keystone's significance in this enlightening journey through Masonic wisdom, culminating in the ethereal Holy Royal Arch. |

Reflections on the Second Degree Work Bro. Draško Miletić offers his reflections on his Second Degree Work – using metaphor, allegory and symbolism to understand the challenges we face as a Fellow Craft Mason to perfect the rough ashlar. |

Diversity and Universality of Masonic Work Explore the rich tapestry of Masonic work, a testament to diversity and universality. Uncover its evolution through the 18th century, from the stabilization of Symbolic Freemasonry to the advent of Scottish rite and the birth of Great Continental Rites. Dive into this fascinating journey of Masonic systems, a unique blend of tradition and innovation. Antonio Jorge explores the diversity and universality of Masonic Work |

Nonsense as a Factor in Soul Growth Although written 100 years ago, this article on retaining humour as a means of self-development and soul growth is as pertinent today as it was then! Let us remember the words of an ancient philosopher who said, when referring to the court jester of a king, “It takes the brightest man in all the land to make the greatest fool.” |

Freemasonry: The Robe of Blue and Gold Three Fates weave this living garment and man himself is the creator of his fates. The triple thread of thought, action, and desire binds him when he enters into the sacred place or seeks admittance to the Lodge, but later this same cord is woven into the wedding garment whose purified folds shroud the sacred spark of his being. - Manly P Hall |

By such a prudent and well regulated course of discipline as may best conduce to the preservation of your corporal and metal faculties in the fullest energy, thereby enabling you to exercise those talents wherewith god has blessed you to his glory and the welfare of your fellow creatures. |

Jacob Ernst's 1870 treatise on the Philosophy of Freemasonry - The theory of Freemasonry is based upon the practice of virtuous principles, inculcating the highest standard of moral excellence. |

Alchemy, like Freemasonry, has two aspects, material and spiritual; the lower aspect being looked upon by initiates as symbolic of the higher. “Gold” is used as a symbol of perfection and the earlier traces of Alchemy are philosophical. A Lecture read before the Albert Edward Rose Croix Chapter No. 87 in 1949. by Ill. Bro. S. H. Perry 32° |

The spirit of the Renaissance is long gone and today's globalized and hesitant man, no matter ideology and confession, is the one that is deprived of resoluteness, of decision making, the one whose opinion doesn't matter. Article by Draško Miletić, |

A Mason's Work in the First Degree Every Mason's experiences are unique - here writer and artist Draško Miletić shares insights from his First Degree Work. |

Initiation and the Lucis Trust The approach of the Lucis Trust to initiation may differ slightly to other Western Esoteric systems and Freemasonry, but the foundation of training for the neophyte to build good moral character and act in useful service to humanity is universal. |

Who were the mysterious 18th century Élus Coëns – a.k.a The Order of Knight-Masons Elect Priests of the Universe – and why did they influence so many other esoteric and para-Masonic Orders? |

Bro. Chris Hatton gives us his personal reflections on the history of the 'house at Blackheath and the Blackheath Orders', in this wonderful tribute to Andrew Stephenson, a remarkable man and Mason. |

Book Review - Cagliostro the Unknown Master The book review of the Cagliostro the Unknown Master, by the Editor of the book |

We explore fascinating and somewhat contentious historical interpretations that Freemasonry originated in ancient Egypt. |

Is Freemasonry esoteric? Yes, no, maybe! |

Egyptian Freemasonry, founder Cagliostro was famed throughout eighteenth century Europe for his reputation as a healer and alchemist |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device