Huguenots were French Protestants who were persecuted for their religious belief. The persecution resulted in a series of conflicts known as the French Wars of Religion.

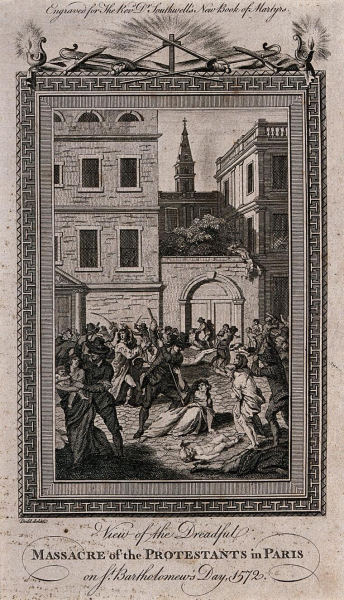

This came to a climax in Paris at the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre on the night of 23/24 August 1572.

The St Bartholomew’s Eve Massacre: men, women and children are thrown out of wi

IMAGE LINKED: wellcome collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

As a supposed effort to restore peace between the warring parties, the Huguenot Prince Henry of Navarre had married Margot, daughter of Catherine de Medici the mother of King Charles IX.

However, there was strong opposition to the marriage, particularly from the staunchly Catholic Guise family, and the Catholic population of Paris was very anti-Huguenot.

A few days after the wedding Admiral Coligny, a major Huguenot leader, was shot, and wounded, in an attempted assassination as he was walking back to his lodgings. The shot came from the upstairs window of a house owned by the Guise.

Fearing there would be a violent Huguenot response to the attempted assassination, King Charles was persuaded, perhaps by his mother and supporters of the Guise, to order a pre-emptive strike against Coligny and the Huguenot leadership.

The disastrous consequence of this decision encouraged the Paris mob to rise up and commit the wholesale slaughter of any Huguenot they could find.

The rioting spread to other parts of the country with the Huguenot death toll perhaps rising to 30,000.

The Huguenots received some protection when Henry of Navarre ascended to the French throne.

In April 1598 he issued The Edict of Nantes granting religious toleration to the Protestants, restoring their civil rights, and the right to work in any field, even for the state, and to bring grievances directly to the king.

Although some of the concessions were chipped away in the subsequent reign of Louis XIII, the edict lasted until October 1685 when it was finally revoked by the Edict of Fontainebleau issued by Louis XIV.

The edict declared that the Protestant religion was illegal, and ordered Protestant ministers to convert to Catholicism, or leave the country within two weeks.

Many Huguenots were alarmed that they were now in danger of further persecution. Although they were forbidden to leave France, as many as 400,000 Huguenots joined the exodus from France to safer havens.

Freemasonry

Jean Theophile Desaguliers

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Jean Theophile Desaguliers is the obvious candidate for the Huguenot who has had the most influence on the development of Modern Freemasonry.

After four London lodges came together on 24 June 1717 to form Premier Grand Lodge, Desaguliers was a key figure in achieving its early success. He became the third Grand Master in 1719 and was later three times Deputy Grand Master.

He helped James Anderson draw up the rules in the “Constitutions of the Freemasons”, published in 1723, and he was active in the establishment of masonic charity. He was born on 12 March 1683 at Aytré, a village near La Rochelle.

Although his father, a Protestant minister, was expelled from France, Jean Théophile was legally required to remain in France to be brought up as a Catholic.

However, he was spirited away, reputedly escaping to Guernsey by hiding in a wine tun. Whether the story is true or not, it underlines the precarious situation in which young Huguenots were placed.

He eventually migrated to England where, as John Theophilus Desaguliers, he was educated, and developed a very successful career, which has been documented by various authors [1,2,3,4]

Defender of the Realm – Charles Delafaye

The Huguenot connections of the Grand Master John, 2nd Duke of Montagu are significant. However, Desaguliers was not the only Huguenot who was active in the early days of Freemasonry.

The Huguenot émigré Charles Delafaye was a member of the Duke of Richmond’s influential Horn Lodge, which met at the Rummer and Grapes Tavern in Channel Row, Westminster, a stone’s throw from Desaguliers’ home.

Delafaye was born on 25 July 1677 in Paris. His father, Louis, had abjured the Catholic faith, and after moving to England had entered the service of the Duke of Ormond.

He later became a French translator of the London Gazette, an official journal of record of the British Government.

Charles matriculated with a BA degree at All Souls College, Oxford in 1696. In 1697 he was appointed secretary to Sir Joseph Williamson, ambassador to the United Provinces.

Following Williamson’s return to England, Delafaye found employment as a clerk in the Secretary of State’s office in 1699, probably because of the influence of his father.

Initially he served in the Southern Department+ as a clerk under James Vernon whose son James became a Freemason.

In 1702 Charles Delafaye was appointed a writer of the London Gazette, because of his facility in the French language. He was promoted to Chief Clerk in December 1706, and assisted the Editor, Richard Steele, from 1707 to 1710 [5].

Charles Delafaye kept a ledger which showed there was an extensive business in the supply of papers, deeply involving a number of government officials.

He was dealing with at least seventy-two individuals spread across England and Ireland with two customers in Scotland and one in Guernsey.

Delafaye’s Huguenot background gave him a personal link with an international clientele. He also supplied eighteen coffee houses, and at the peak of his business he was sending out four to five hundred copies a week [6].

In August 1713 the Duke of Shrewsbury, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, appointed Delafaye to be his Ulster Secretary.

This promotion elevated Delafaye from the relative obscurity of a clerk to the greater responsibility of a secretary to a prominent political master, with whose fortunes he was now inextricably linked.

In August 1715 the Irish administration was taken over by the Duke of Grafton and the Earl of Galway, with Delafaye being made one of their joint secretaries.

In order to bolster the government representation in the Irish House of Commons, Delafaye was found a seat as one of the members for Belturbet, co. Cavan, which he held until 1727 [7].

The Southern Department was responsible for government dealings with countries such as France, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Greece, and the Ottoman Empire. The Northern Department looked after affairs with the northern European powers.

He returned to London in April 1717 as Sunderland’s Under Secretary at the Northern Department. He was also a Justice of the Peace for Westminster for about twenty years. He served alongside many Freemasons as magistrates on the London benches.

One of his early published court reports in 1717 was that dealing with a Jacobite sympathiser who had publicly declared in St James Park that the Pretender, James Stuart, was the lawful king.

His judicial decisions, made from the standpoint of a loyal supporter of the Whig government, probably encouraged his adjudication in cases with a political connotation [8].

Charles Delafaye had an intriguing professional relationship with the Secret Department of the Post Office.

The General Post office (GPO) was established by Charles II in 1660. The predecessor to the Secret Department of the Post Office was the GPO Special Investigations Unit responsible for intercepting letters as part of the British government’s intelligence effort.

Branches of the unit were established in every major sorting office in the UK, with headquarters in St Martin Le Grand GPO near St Paul’s Cathedral.

In Robert Walpole’s time similar units were set up in key European cities, often with the objective of intercepting the mail of Jacobite sympathisers who might be plotting seditious activity against the British state.

Intercepted letters were steamed open, read, and if necessary decoded, recorded and the information passed onto the intelligence services, usually involving Charles Delafaye. The resealed communication was then forwarded to the addressee.

The interception procedure was normally authorised by a warrant issued by a Secretary of State [9].

As well as the intelligence information supplied by the Secret Department of the Post Office, Delafaye was receiving intelligence from other sources:

information arising from the international network of the British diplomatic service;

details of ship movements from port officials;

reports from government spies operating in Masonic Lodges, particularly those thought to contain Jacobite sympathisers, and paid informers.

Delafaye reported to the appropriate Secretary of State. The intelligence gathering operation was funded by “off-the-books” money from Crown sources.

Delafaye played an active part in foiling the Atterbury Plot (circa 1722), a Jacobite conspiracy to place James Stuart on the English throne as James III. A central figure in the plot was Francis Atterbury (1663-1732), Bishop of Rochester.

Various prominent men were involved in the conspiracy including Lord North and Grey, the Earl of Orrery, and Sir Henry Goring. The principal Jacobite secret agents were John Plunket, George Kelly, and Christopher Layer.

There was not enough definitive evidence to convict Atterbury of treason, but Parliament stripped him of his bishopric, and sent him into permanent exile He served for some time as James Stuart’s Secretary of State.

John Plunket spent the rest of his life in the Tower of London; George Kelly was imprisoned for fourteen years before escaping to France, and Christopher Layer was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn on 17 May1723 [10].

Delafaye had managed the interception and deciphering of correspondence between Atterbury and Lord Mar and had the professional satisfaction of escorting Atterbury to his prison cell in the Tower while awaiting further investigation.

The Duke of Wharton, Grand Master of Premier Grand Lodge (1722/23), but a closet Jacobite supporter, was enraged by Atterbury’s arrest.

His Jacobite sympathies had come to the surface when he had encouraged the band to play Jacobite songs at an Annual Feast in Stationers’ Hall at his installation as Grand Master in 1722 [11].

He was severely admonished by Desaguliers for this disloyal and reckless action.

Delafaye was at the centre of the British intelligence network for almost fifteen years. He achieved the reputation, to those of his colleagues in the know, as the government’s Spy Master General and was regarded as one of the government’s most reliable officials [12].

Delafaye’s reputation helped to reinforce the acceptance of Freemasonry by the Establishment. Despite his time-consuming duties as a government official, he still found time to participate in the ritual and festivities of the Lodge.

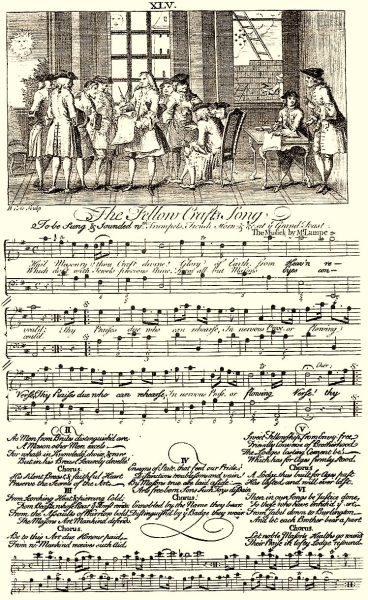

Benjamin Franklin’s 1734 reprint of Anderson’s 1723 Constitutions contains the Fellow Craft’s song composed by Delafaye. The first verse clearly expresses Delafaye’s admiration for Freemasonry:

Hail, Masonry, thou Craft divine!

Glory of Earth, from Heav’n reveal’d;

Which dost with Jewels precious shine,

From all but Masons Eyes conceal’d.

[13]

One of the best-known table songs of old English Freemasonry with the much-quoted opening lines: “Hail Masonry Thou Craft divine.” The poet is Charles Delafaye, who was a member of the Lodge at Horn’s Tavern, London, about 1723.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

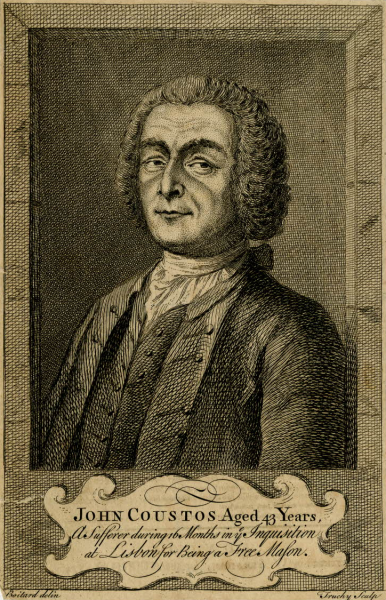

John Coustos

ohn Coustos – frontispiece to ‘Sufferings in the Inquisition’, 1746 (British Museum)

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

John Coustos suffered for Freemasonry. He was born in Berne around 1703. His father was Isaac Coustos, a Huguenot exile from Guienne in France, and a medical doctor.

His mother was Marie née Roman. The family moved to England in 1716, the father and son becoming naturalized British citizens.

John trained in lapidary, establishing a jewellery and diamond cutting business at St Giles, London. He also dealt in precious stones. Coustos married Alice Barbutt who was born in London into a family of French descent.

In 1730 Coustos was initiated into Freemason’s Lodge No. 75 meeting at the Rainbow Coffee House, York Buildings, London.

He was presented with a pair of white gloves on his initiation. The same year he was a Founder of Lodge No. 98, meeting at Prince Eugene’s Coffee House, St Alban’s Street, London [14].

He was also a member of the Union French Lodge in London, along with Desaguliers [15].

Somewhere along the line John Coustos became a spy for Robert Walpole’s intelligence network [16,17].

In 1735 he moved to Paris, ostensibly to practice his trade in the galleries of the Louvre. However, there may have been a covert reason for this move, connected with the political circumstances of the time, and his obligations to Robert Walpole.

According to a tradition dating to 1777, the first Masonic Lodge in France was founded in 1688 by the Royal Irish Regiment, which followed James II of England into exile, under the name “La Parfaite Égalité” of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

The same can be said of the first lodge of English origin, “Amitié et Fraternité”, founded in 1721 at Dunkerque.

The first Lodge whose existence is historically certain was founded by some Englishmen in Paris “around the year 1725”.

It met at the house of the traiteur (caterer) Huré on rue des Boucheries, “in the manner of English societies”, and mainly brought together Irishmen and Jacobite exiles [18].

In 1728 Philip Wharton was recognised as “The Grand Master of the Freemasons in France”, followed by the Jacobite James Hector MacLean, and then the Earl of Derwentwater [19].

Thus by the time that Coustos was relocating to Paris in 1736 there was a small network of Jacobite- sympathising Lodges whose private spaces could used for anti-Hanoverian intrigue.

Charles Radcliffe 5th Earl of Derwentwater was a person of particular interest to the British Government.

He had fought in the Jacobite Rising of 1715, been captured, tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

However, he managed to escape from Newgate Prison, fled to Italy then moved to Paris, married, and was commissioned into the Charles Fitz-James’s Regiment. He co-founded Masonic Lodges in Paris around 1725.

Members of the exiled Jacobite community were strongly represented in the membership [20].

Chevalier Andrew Michael de Ramsay

IMAGE LINKED: chevalierramsay.be/chevalier-andrew-ramsay/ (CC BY 4.0)

Into this milieu stepped the Chevalier Andrew Michael de Ramsay. He was once thought to have risen from the obscurity of a baker’s son in Ayr, Scotland.

However, fairly recently, Christopher Powell has unearthed a 1716 letter by Ramsay in the Royal Archives at Windsor (C. Powell, AQC , 131,(London, Oct. 2018), pp. 309-316).

The letter shows that Ramsay was born at Abbots Hall in Fife, the son of the Revd Alexander Ramsay and his second wife Jean Orrock(or Orek), and was christened on 21 June 1693.

Ramsay went to France in 1710, becoming the confidant of Archbishop Fénelon of Cambrai who converted him to Catholicism.

He was also associated with Jeanne Marie Bouvier de la Motte, a Quietist mystic. Following Fénelon’s death, he returned to Scotland to fight for the Jacobite cause at the Battle of Preston (November 1715).

He was captured, jailed, transported from Liverpool by ship bound for St Christopher’s Island (now St Kitts), but managed to escape to L’Aiguillon-sur-Mer north of La Rochelle.

Ramsay settled in France, writing a politico-theological treatise dedicated to the Old Pretender, James Francis Edward Stewart.

In 1722 he became involved in high level negotiations about tax on the assets of Jacobite exiles proposed by the British government. In 1723 he was knighted into the Order of St Lazarus of Jerusalem [21].

In January 1724 he was sent to Rome on a short-lived appointment to tutor James’s two sons, Charles Edward, and Henry.

Through his association with Fénelon, Ramsay came to the notice of the nobility, particularly the Comte de Sassenage whose sons he tutored for about four years.

Surprisingly, in view of his Jacobite views, Ramsay was initiated, by the Duke of Richmond, into English Freemasonry at the Horn Lodge on 9 March 1730.

Perhaps the fraternity thought it was better to have him inside the Masonic tent, where they could keep an eye on him?

Derwentwater persuaded Ramsay to deliver an oration to a Parisian Lodge on 26 December 1736, the day before Derwentwater was due to be elected Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of France.

Although Ramsay started from a similar point to Anderson in his Constitutions, he romanticised the origins of Freemasonry by suggesting it stemmed from ancient Egypt, Abraham, and the Jewish patriarchs [22].

Ramsay’s reformulation of Freemasonry, in a chivalric mode, placed the Knights Templar as the progenitors of Modern Freemasonry, distinguished from its English counterpart by placing Christianity as its spiritual belief system [23].

Ramsay’s version of Freemasonry resonated with the French nobility’s love of splendid ritual, leading to an influx of aristocrats, and the mercantile bourgeoisie.

Thus, it was hardly accidental that Coustos formed a Lodge on 28 December 1736, encouraging Jacobite sympathisers to join, thus facilitating his espionage activities.

Coustos claimed that Louis XV asked him to initiate a favourite and senior courtier, the Duc de Villeroy, into Freemasonry.

It was known that the King had an interest in Freemasonry and may have visited an English Lodge as a guest of the Duke of Norfolk.

The request was acceded to. Villeroy became the Master (or Vénérable) with Coustos as his Deputy, and the Lodge renamed ‘Villeroy-Coustos’ [24].

But another hand intervened to tighten the grip on Freemasonry. Cardinal Fleury, Louis XV’s chief minister, had a long-standing suspicion of Freemasonry, and its growing influence in France.

His attitude was inflamed when, in March 1737, Ramsay sent him an edited version of his oration, hoping to gain approval for its presentation to a meeting of Mason’s, and to gain Fleury’s approval of the Craft.

The Cardinal responded by branding Freemasons as traitors and banning their assemblies. Loge Villeroy-Coustos was included in the subsequent police raids, closed down, and the Minute books and other records confiscated.

This ban, and other investigations by the Inquisition into Italian Freemasonry, led to Pope Clement XII’s promulgation of In eminenti apostolatus in 1738, the first papal bull placing an interdiction against Freemasonry [25].

John Coustos stayed in Paris until about 1741, subsequently moving to Lisbon where he hoped to get the necessary travel documents to enable him to go to Brazil to profit from the recent discovery of diamonds.

His petition was ignored by the Portuguese authorities, obliging him to stay in the city as a diamond cutter.

But Coustos’s haste to establish a Lodge suggests he might have had a covert reason for its formation.

The presence of nine French nationals: four merchants, three jewellers, a gun smith, and possibly the tailor to the French Ambassador in the Lodge provided a ready source for information gathering.

Two Englishmen, a book seller and a jeweller, a Scot, a Dutch jeweller, and Mr Gordon, of unknown occupation, completed this band of cosmopolitan Freemasons [26].

Pope Clement XII’s 1738 edict denouncing Freemasonry often obliged the fraternity to meet in private houses in those areas where In eminenti apostolatus had been ratified by the local authority. Such was the case in Lisbon.

Unfortunately for Coustos a woman, with whom he was acquainted, informed the Inquisition where and when he and his Brethren met.

As if this was not enough, she then proceeded to accuse him and his wardens of lewd and scandalous behaviour, as well as stealing a diamond.

He was brought before the President of the Inquisition and four Inquisitors and requested to make a full confession of all the crimes he had committed during his life.

Coustos responded that “he had been taught to confess not to man but to God”.

He was returned to his prison cell but brought before the Inquisition after three days.

It now emerged that the Inquisition was more interested in his Masonic activities than any supposed immoral behaviour or larceny [27].

For the next few weeks, he was periodically interrogated about Freemasonry. It was put to him that, if Freemasonry was so virtuous, why shouldn’t he reveal its secrets?

Among other requests for information, he was asked about the “Tenets” of the Craft, and whether any Portuguese had been admitted into Freemasonry.

Coustos refused to answer and was returned to the dungeon. A few days later he appeared before the Inquisitors, who demanded he reveal the secrets of Freemasonry, under threat of serious consequences if he refused to answer.

Coustos said it would be a betrayal of his Masonic obligations to answer [28].

Despite Coustos having assured the Inquisition that Freemasons took an oath on the Bible, that they would be faithful to the King (of Portugal), would not enter into any conspiracies against the Monarch, obey the law and magistrates of the country in which they resided, and that their purposes were charitable, the Inquisition resorted to torture.

He was subjected to a number of sessions of excruciating torture, aimed not only at getting him to reveal Masonic secrets, but to convert to the Roman Catholic faith.

Coustos implacably refused, with the result that he was put on trial for heresy, convicted, then sentenced on 21 June 1744 to four years on a galley.

However, he was suffering so much from his injuries that he was soon transferred to a hospital.

He managed to persuade someone to write to his brother-in-law, Mr Barbutt, who was a member of the Earl of Harrington’s household. The Earl was Secretary of State for the Northern Department and a Freemason.

He interceded on Coustos’s behalf, approaching the Duke of Newcastle, also a Freemason, who persuaded George II to instruct Charles Compton, British ambassador in Lisbon, to petition the King of Portugal for Coustos’s release, which was granted in October 1744 [29].

Back in London in Coustos wrote ‘The Sufferings of John Coustos for Freemasonry and for refusing to turn Roman Catholic in the Inquisition at Lisbon’, printed in 1746 by William Strahan, though not a Freemason, a lifelong friend of Benjamin Franklin [30].

The book was dedicated to the Earl of Harrington, the second edition containing fourteen pages of subscribers, including Lord Cranston the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of England.

The 1746 first edition was not a financial success, forcing Coustos into a debtor’s prison from where he had to petition The Duke of Newcastle for funds for his release. Later editions were a publishing success and, even today facsimile copies of earlier editions are available.

A first edition was recently advertised for sale for $3600 [31].

Other Huguenots working for the secret department of the post office included the Chief Clerk, John Le Febure [32] (member of Kings Head Lodge), and his assistants Peter Thouvois and Peter Hemet (member of Bedford Head Lodge).

Anthony Corbière, a Huguenot and Fellow of Trinity College Cambridge, was employed as a government decipherer and translator from 1715. He testified to a committee of The House of Lords against Bishop Atterbury in 1722 [33].

Apart from those directly working in intelligence gathering, there was a significant number of Huguenots employed in other government departments.

For example, John Anthony Balaguier (Lord Carteret’s agent); John Couraud (a senior clerk at the Southern Department); Daniel Prevereau (Chief Clerk at the Southern Department under Delafaye) [34]; John Larpent (Chief Clerk at the Northern Department) [35], and his uncle and father-in-law, James Payzant, clerk and translator for over seventy years to seventeen Secretaries of State [36]. The latter died a centenarian in July 1757 [37].

Huguenot Lodges in London

The city was the principal English location in which many Huguenots chose to settle.

They brought with them a wealth of artisan and professional skills: silk weaving, working in silver and gold, watch and clock making, publishing (Roget’s Thesaurus), acting (David Garrick), sculpting (Roubiliac), and financial administration, Sir John Houblon the first Governor of the Bank of England among them.

Huguenots were active participants in early Freemasonry, and they were members of a number of London Lodges, often know as ‘French Lodges’.

Details of membership of selected Huguenot Lodges are given in Table 1 to Table 3 below. Extracting the information was not always straightforward.

The Lodge membership lists did not always include a first name or even the initial of a first name.

This difficulty was compounded when alternative spellings of a surname had to be considered, such as in the case of Debat/DeBat/deBat for example.

Thus, it was not always possible to identify a Lodge membership entry with a single individual, and options had to be given.

This investigation necessarily focused on London because that is where modern Freemasonry was founded.

However, Freemasonry inevitably spread to other towns and cities in Great Britain where Huguenots had settled, and it would be an interesting matter of further research to discover what involvement they had in local Freemasonry.

It is well known that Huguenot officers and soldiers were employed by the British army, particularly after the Glorious Revolution ushered in by William III.

It is quite likely that some Huguenots became members of military Lodges, which had a significant role to play in helping to spread Freemasonry throughout the World.

The information presented in Tables 1 to 3 clearly show that Huguenot Freemasons were engaged in a wide range of occupations ranging from skilled craftsmen such as watchmakers to men of significant influence in government such as Charles Delahaye.

Another significant feature of these Huguenot Freemasons is their participation in the religious community built around the French Churches in the London of the first half of the 18th century.

Although the Huguenot community would gradually be absorbed into the native English population with the passage of time, the involvement of a significant number of Huguenots in the early days of Freemasonry helped to build the solid base which eventually developed into an international fraternity.

‘Noon’ from Four Times of the Day by William Hogarth. The picture shows Huguenots leaving the French Church in what is now Soho.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Members of French Lodges

- Table 1 - Solomon’s Temple Lodge

- Table 2 - King’s Head Lodge

- Table 3 - Swan Tavern

- French Lodges C18th London

The Members of Solomon’s Temple Lodge – 1725

[38,39]

The Members of King’s Head Lodge, Pall Mall – 1725

[50]

| Mr Jean Milxan (Master) | See Table 1 |

| Mr Sandys (Warden) | A . W. (William ?) Sandys is listed as a clerk to an Under Secretary of State in 1727 51. Charles Delafaye, a prominent Freemason, was Under Secretary to Newcastle at the time. Other possibilities are Richard Sandys(Trader) or Henry Sandys(Architect & Decorator)52. |

| Mr Rading (Warden) | No information found |

| Mr Edward Lambert | Celebrated confectioner. Author of T he Art of Confectionery, London c. 1744 .Hannah Glasse heavily plagiarised his work in The Compleat Confectioner53.Lambert counted Robert Walpole among his clients. |

| Mr Francis Nicholls | Reader in Anatomy at Oxford. Physician to George 11(1753-60). Elected Fellow of the Royal Society (1728)54 . Sponsors included Dr William Rutty, a Freemason of the Bedford Head Lodge. |

| Mr John Renier (or Raynor) | Jouachin Renier, a baker, was present at the baptism of his son Jean at The Wheeler Street Church on 24 June 1711. |

| Mr Richar | No information found |

| Mr Goodwin | Possibly Henry Goodwin (master haberdasher) or NicholasGoodwin (draper)55. |

| Mr Clark | Possibly Edward Clark, broker. |

| Mr Creek | No information found |

| Mr fflower | Possibly Robert Flower, haberdasher. |

| Mr ffavre(John Le Favre[ Le Febure]) | Foreign Secretary at the Post Office ( cf. Charles Delafaye)56,57. |

| Mr Guidon | Lewis Guidon received Denization on 26 January 1705. |

| Gabriel Guidon was a Temoins (P) at the baptism of Louise Guitteau on 30 August 1750 at the Threadneedle Street Church. | |

| Jacob Guidon was a Temoins (P) at the baptism of Marianne Marioge on 7 March 1703 at The Church of Hungerford Market. Her father, Jean, was a wig maker. |

Members of the French Lodge at the Swan Tavern, Long Acre, Covent Garden, 1730

[58]

|

John Oliver |

Is this ‘Olivier, John, of St Giles in Fields(deceased) 20 Nov. 1736 to Catherine, the widow.(Huguenot Wills-B307/11)’? |

|

John Milxan |

See Table 1. Milxan, John, of St Martin in Fields, widower.5 Mar. 1778 son John renouncing, to John Lambert, administrator of Mary Lambert, formerly Massia, daughter of deceased. (Huguenot Wills C259/4) |

|

Ezekiel Varenne |

Apothecary59. |

|

Charles Raboteau |

Merchant. Married to d’Anne Esther Regnaud, sister of Elias Regnaud 60. |

|

Elias Regnaud |

Merchant of the Parish of St Giles in the Fields. Brother-in-law of Charles Raboteau. Naturalised 1 May 170961. |

|

James Bernardeau |

Notable razor maker and cutler of the Pistol and L in Russel Court, Drury Lane. Known for his classically elaborate business cards62. |

|

James Bousseau |

Perhaps a distant relative of the French sculptor Jaques Bousseau. |

|

Daniel Simons |

Various Simon(s) listed in the registers of the French Church at Threadneedle Street |

|

Anthony Meymac |

Antoine Meymac married Marianne Crespain at the French Church Threadneedle Street on 13 September 1730.63 |

|

Francis Mailliet |

Tailor. MAILLIET(Baptism). 9 Avr. (1703 ) Marie Anne, ff. de François, tailleur, et de Charlotte, dem. au coin de Jarret Street à la Charrue, vis-à-vis l’enseigne du Cigne Blanc, par. de Ste. Anne. Min. Mr Roussilhon. Tem. Anne Costel64. |

|

Rev. Jean d’Agneaux |

Minister of La Patente, Soho. In March 1720 he also became the minister for the West Street Church65.He is later recorded, in 1726, as the minister for the Church at Rider Court66. |

|

Rev. George Cantier |

Minister of Le Quarré, Castle Street in 172767. |

|

Rev. Jean Stehelin |

Minister at La Patente, Soho. Minister at Leicester Fields in 1739.Skilled linguist in Hebrew, Greek,Latin, French, German, Italian, Danish, Dutch, Coptik, Armenian, Syriac, Arabic, Old Tedesco or Druid, Anglo Saxon, Spanish, Chaldean, Gothic, Spanish, Portuguese and Welsh68. Elected Fellow of The Royal Society 8 November 1739 d. July 175369. |

|

Rev. Daniel de Beaufort |

De Beaufort ordained into the Church of England. Appointed to the living of St Martin Orgar in the City of London, where French Protestants then worshipped, and officiated at the Savoy Chapel. Became rector of St Mary the Virgin church, East Barnet, in 1739, which from 1741 he combined with his duties at the Little Savoy. Left East Barnet in 1743, succeeded by Samuel Grove70. De Beaufort’sgrandson was the inventor of the Beaufort Scale. |

|

T.P Duvall |

Member of the extensive Huguenot family of Duvalls 71. Twelve of the Duvalls were appointed directors of La Providence between 1776 and 190872. |

|

Pierre MacCulloch |

Macculloch married Elizabeth Savonnet in the French Chapel of St James on 18 May 172773. He was listed as a Temoins (P) at the baptism of Catherine Dupin, daughter of d’Aimé and Ann la Combeon 1 October 1730. Baptised by Msr J. Pierre Stéhelin at la Patente de Soho74. |

|

John Combecrose |

Apothecary. Sponsor of Louisa Guerin, d. of John Guerin and Mary, to the French Protestant School (Founded 1747)75.He made a donation of £10 to the school, worth £1800 today76. He was also a director of the school. |

|

Jaques de Mare |

Demar(s), James, West St, over against the French chapel, by Grafton St, Soho. London carver and gilder (1723–27). Named in the Montrose papers in 1723 and 1725 supplying carved and gilt table frames; a frame for ‘Montrose’s Great Grandfather’, James, 2nd Marquis in 1723; and a ‘Rich carved & gilt picture frame’, costing £13, in 1726 77. |

|

William Read |

Apothecary of Hatton Garden. Advertised a cure for lunatics in the London Gazette78. |

|

Gabriel Garnier |

Isaac Garnier was a Huguenot apothecary who sought refuge in England in1682.He was very successful, being appointed by Queen Mary as the first apothecary at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea in 1691. His son, Isaac II became a Freeman of The Society of Apothecaries. He had a shop in Pall Mall, and died a wealthy man in 173679. |

|

Gabriel Garnier was probably an apothecary and member of this family. His son, Jean was baptiseWed at the Church of the Savoy in Spring Gardens on 19 May 1732.Daniel Grignion the watchmaker(see Table 1) was a Temoins(Pere) as was his wife Elénore(Mere).Gabriel’s wife, Elizabeth was Daniel Grignion’ssister80 . |

|

|

` |

He was baptised at the French Church, Threadneedle Street on December 23, 167581 and naturalised 82 in 1713. A number of Blanchards were goldsmiths, but an Isaac Blanchard was admitted to La Providence on August 1741, dying June 20 1746. |

|

Anne Blanchard who was admitted to La Providence on June 13 1767 was recorded as previously living at the house of a Mr Blanchard at a haberdashery “vix-a-vis” York Buildings in the Strand. The latter was probably the son of Isaac Blanchard, suggesting father and son were both haberdashers83. |

|

|

Jean Massia |

Jean and Marie Massia were Temoins at the marriage of Guillaume Coupe and Cecile Neveu at St Martin’s des Champs, 14 July 172584. Marie Massia aged 60 years, née Milxan(see Table 1), widow of Jean Massia, was admitted to La Providence on February 20, 1749/50. She also asked to be placed on the widows’ list for la Pension defeu85. |

|

John Mercadie |

TURENE. 1742/3, 24 Fév. Anne, ff. de Jean, et de Louise ; bat. par Jean Blanc, min. P. Jean Mercadier. M. Anne Borland. Née 17 Fév86. |

|

Stephen Demainbray |

Stephen Charles Triboudet Demainbray (1710-82), a pupil at Westminster School, stayed with the Desaguliers family at Channel Row. His Protestant father had reached England from France via Holland. Demainbray’s classical education at Westminster was augmented by science from Desaguliers, whom he regarded as his mentor. He was an early astronomer at the King’s Observatory at Kew. His collection of scientific instruments is in the King George III Collection at the London Science Museum87. His son, Stephen George Francis Demainbray (1758-1854), followed him in that position, preceding Stephen Peter Rigaud, appointed third director of astronomy at the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford in 182688. |

|

Isaac Micheaie and Thomas Hall |

Some other French Lodges in 18th century London

| Name of Lodge | Year of Warrant |

| French Lodge | 1723 |

| Union French Lodge | 1732 |

| Lodge of St George de L’Observance | 1736 |

| Old French Lodge | 1742 |

| Loge L’Ésperance | 1754 |

| French Lodge | 1765 |

| L’Immortalité | 1766 |

| Loge des Amis Reunis | 1774 |

| Loge Parfaite Égalité Lyonnese | 1774 |

| Loge L’Égalité | 1785 |

Footnotes

Research

1. R. Berman, ‘Foundations: New Light on the Formation and early Years of the Grand Lodge of England’, Ars Quatuor Coronatorum,129 (2016), pp 200-202.

2. The Library of Freemasonry, BE 68 (DES) WAD fol. ‘From Huguenot Refugee to third Grand master’/paper presented to the Stationers’ Company School Lodge No7460 by W.Bro. Dr. Nigel Victor Wade, Friday 11 December, 2009.

3. R.A. Berman, ‘John Theophilus Desaguliers: Homo Masonicus, in The Architect s of Eighteenth Century Freemasonry, 1720-1740,(Thesis: University of Exeter, 15 December, 2010), pp 70-110.

4. A. Carpenter, John Theophilu s Desaguliers: a Natural Philosopher, Engineer and Freemason in Newtonian England, (London, 2011).

5. R.A. Berman, ‘Charles Delafaye, loyalty personified’, in The Architects of Eighteenth Century Freemasonry, 1720-1740, (Thesis: University of Exeter, 15 December, 2010), pp 133.

6. M. Harris, A Study of the Origins of the Modern English Press, (Rutherford, N.J., June 1987), pp 44-45.

7. J.C. Sainty, ‘Delafaye, Charles’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/39578 [Accessed 26 July 2019].

8. R.A. Berman, ‘Charles Delafaye, loyalty personified’ ,The Architects of Eighteenth Century Freemasonry, 1720-1740, (Thesis: University of Exeter, 15 December 2010), pp 133-134.

9. ‘General Post Office’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Post_Office#Links_to_the_intelligence_services [Accessed 27 July 2019].

10. ‘Under Covers: Documenting Spies, The Atterbury Plot, www.lib.cam.ac.uk/exhibitions/Spies/Atterbury.html [Accessed 29 July 2019].

11. E. Cruikshanks, ‘Lord Cowper, Lord Orrery, the Duke of Wharton, and Jacobitism’, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 26(No 1) (1994), p 39.

12. R.A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), p.59.

13. J. Anderson, B.Franklin, P.Royster (Edit.), The Constitutions of the Free-Masons(1734).An Online Electronic Edition, (University of Nebraska, 2006), p.89.

14. ‘Engraving of John Coustos’, file:///D:/Documents%20and%20Settings/user/My%20Documents/John%20Coustos.htm[Accessed 1 August 2019].

15. A. Carpenter, John Theophilu s Desaguliers:a Natural Philosopher, Engineer and Freemason in Newtonian England, (London, 2011), reference No 55 to notes on pp 103-108, p279.

16. M. K.Suchard, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Secret Agent on Earth and in Heaven: Jacobites, Jews and Freemasons in Early Modern Sweden, (Boston, 2012), p 237.

17. R.A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), p 162.

18. ‘The History of Freemasonry in France’,

file:///D:/Documents%20and%20Settings/user/My%20Documents/History%20of%20Freemasonry%20in%20Fr

19. ibid.

20. R. A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), p 164.

21. ‘Andre Michael Ramsay’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Michael_Ramsay [Accessed 1 August 2019].

22. Ibid, Berman, p166.

23. Études Maçonnique by W. Bro. Alain Bernheim 33o- Ramsay and his Discours Revisited, http://www.freemasons-freemasonry.com/bernheim_ramsay02.html [Accessed 5 August 2019].

24. M.K. Suchard, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Secret Agent on Earth and in Heaven: Jacobites, Jews and Freemasons in Early Modern Sweden, (Boston, 2012), pp 237-238.

25. ‘The Papal Ban on Freemasonry’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papal_ban_of_Freemasonry#In_eminenti_apostolatus[Accessed 8 August 2019]

26. .A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), p 174.

27. ‘The Torture of John Coustos’, https://www.lodge76.co.uk/lectures/the_torture_of_john_coustos.htm

p. 2 [Accessed 19 August 2019]

28. Ibid.

29. A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), pp 182-184.

30. N. Wade, ‘Benjamin Franklin and a Master of the Stationers’ Company’, The Old Stationer, 84 (March 2017), pp 22-24.

31. Timeless Tokens DE, https://www.rubylane.com/item/1475848-H14002/Antique-Book-Sufferings-John-Coustos-for, [Accessed 19 August 2019].

32. P.S. Fritz, ‘The Anti-Jacobite Intelligence System of the English Ministers, 1715-1745’, The Historical Journal, 16(No.2), (June 1973), p 268.

33. Ibid p 270.

34. R. A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), pp108-109.

35. L.G. Layton, ‘James Payzant (1657-1757), French refugee, British civil servant and centenarian’, The Huguenot Society Journal, 30 (No2) (Autumn 2014), p 231.

36. Ibid. pp 223-224.

37. Ibid. p 229.

38. Private communication. The assistant Librarian, Freemason’s Hall, Queen Street London.

39. A. Berman, ‘Spymaster General’, in Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017),pp 264-5.

40. A.M. La Touche, ‘Some Records of the Family of Digues de La Touche’, Huguenot Society Proceedings, (No 2), (1916), p 227.

41. G Le Mauff, ‘The domain of La Touche in the Blésois’, Huguenot Society Journal, 32, (2019), pp 55-61.

42. C.F.A. ’The Chelsea Pensioner & the Chaplain: The Two Jacques Duplessis, Proc. Huguenot. Society., 23 (No. 1), 1977, p.46.

43. J Evans, Huguenot Goldsmiths in England and Ireland , Proc.Hug. Soc., 14(No.4), 1932-3,p 529.

44. J.M. Shaftesley & M. Rosenbaum, Jews in English Regular Freemasonry 1717-1860, Trans. & Misc.(Jewish Historical Society, 25, 1973-75, p174.

45. T. Murdoch, Second Generation Huguenot Craftsmen in London: from the ‘Warning Carrier Walks’, Proc. Hug. Soc. 26 (No.2), 1995, p242.

46. W. Minet & S. Minet, Register of the Tabernacle at Glasshouse Street & Leicester Fields: 1688-1783, Quarto Series Hug. Soc.29, 1926, p.35.

47. James Parmentier, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Parmentier, [accessed 20 December 2019].

48. C.Labelye, A short account of the methods made use of in laying t he foundation piers of Westminster Bridge…, RA collection (No.03/2633),Printed by A. Parker for the author, London, 1739.

49. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thuret_family, [accessed 14 January 2020].

50. W. J. Songhurst (Edit.), ‘The Minutes of the Grand Lodgeof Freemasons of England, 1723-1739’, Quatuor Coronatorum Antigraphica, 10, (1913), pp 33-34.

51. ‘Office-Holders in Modern Britain: Volume 2, Officials of the Secretaries of State 1660-1782, ed. J.C. Sainty (London, 1973), pp. 22-58. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol2/pp22-58 [Accessed 15 January 2020].

52. R. Berman, Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), p. 270.

53. A. Davison, The Oxford Companion to Food, 3rd ed, (Oxford, 2014), p. 350.

54 ‘The Royal Society-Fellows Details’, https://collections.royalsociety.org/DServe.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqDb=Persons&dsqSearch=Code==%27NA5253%27&dsqCmd=Show.tcl, [Accessed 16 January 2020].

55 ‘London Metropolitan Archives’, https://search.lma.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll?logon&application=UNION_VIEW&language=144&file=[WWW_LMA]home.html, [accessed 20 January 2020 ].

56 J. Chamberlayne, Magnae Britaniae Notitia, Or the Present State of Great Britain, (London , 1716), p.682.

57 R. Berman, Espionage, Diplomacy & The Lodge, (Oxfordshire, 2017), pp. 93-99.

58 W.J. Songhurst (Edit.), ‘The Minutes of the Grand Lodge of Freemasons of England, 1723-1739’, Quatuor Coronatorum Antigraphica, 10, (1913), pp 159-160.

59 ‘Huguenot Wills and Administrations in England and Ireland 1617-1849’, The Huguenot Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 60(2007), p 360.

60 ‘Register of the French Church at West Street’, The Huguenot Society of London, 32 (1929), p32.

61 ‘Supplement to Dr W.A Shaw’s Letters of Denization and Acts of Naturalization’, Quarto Series ,The Huguenot Society of London, 35 (1932), p15.

62 M. Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth Century Britain,(Oxford, 2007), p. 275.

63 W. Minet and S. Minet,(Edits.), ‘Register of the Church of Rider Court, London’, The Huguenot Society of London, 30 (1927), p.43.

64 W.Minet and S. Minet (Edits.), ‘Register of the Church of Le Carré and Berwick St’, The Huguenot Society of London, 25 (1921), p.9.

65 W. Minet and S. Minet (Edits.), ‘Registres des Quatres Eglises du Petit Charenton de West Street de Pearl Street et de Crispin Street’, The Huguenot Society of London, 32 (1929), pp. xvi-xvii.

66 W.Minet and S. Minet (Edits.), ‘Register of the Church at Rider Court 1700-1738’, The Huguenot Society of London, 30 (1927), p. xi.

67 W.H. Mancheé , ‘Huguenot Clergy’, Proc Huguenot Society of London., 11(No.2) (1915), p.272.

68 J. Southerden Burn, The History of the French, Walloon, Dutch and Other Foreign Refugees Settled in England, (London, 1846), p. 137.

69 ‘List of Fellows of The Royal Society, S,T,U,V’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fellows_of_the_Royal_Society_S,_T,_U,_V#S, [accessed 17 February 2020 ].

70 ‘Daniel Cornelius de Beaufort’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Cornelius_de_Beaufort , [accessed 18 February 2020].

71 Anon., ‘Pedigree of Duval’, Proc. Huguenot Society of London, 9(No1) (1909-1911), pp. 117-119.

72 H. Wagner, ‘Directors of the French Hospital at La Providence’, Proc. Huguenot Society of London’, 10 (1912-1914), p. 145.

73 W. Minet and S. Minet (Edits.), ‘Registers of the Chapel Royal of St James( 1700-1756), and Swallow Street (1690-1709)’, Quarto Series ,The Huguenot Society of London, 28 (1924), p.2.

74 W. Minet and S. Minet (Edits.), ‘Registers of La Patente de Soho, Wheeler Street, Swanfields, Hoxton and The Repetoire Generale’, Quarto Series, The Huguenot Society of London, 45 (1956), p.34.

75 W. M. Beaufort (Secty.), ‘Records of the French Protestant School’, Proc. Huguenot Society of London, 4(Issue4) (1891-1892), p.424.

76 ibid, p.464

77 Dictionary of English Furniture Makers: 1660-1840, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/dict-english-furniture-makers/d, [accessed 23 February 2020].

78 Advertisment, London Gazette 5 September 1719, p.2.

79 Registers of the Church of the Savoy at Spring Gardens, Quarto Series, Publications of the Huguenot Society of London, 26 (1922), p. 73.

80 L.G. Mathews, ‘Immigrant Apothecaries, 1600-1800’, Cambridge Journal of Medical History, 18 (No 3) (July 1974), pp.262-274.

81 W.J.C. Moens, Registers of the French Church, Threadneedle Street, 2, Quarto Series, Publications of The Huguenot Society of London, 13 (1899).

82 Letters of Denization and Naturalization for Aliens in England and Ireland, 1701-1800, Th Publications of The Huguenot Society of London, 27 (1923), p.116.

83 C.F.A. Marmoy, ‘ Extracts from the Archives of La Providence, 1718-1957 and 1745-1901 Vol. 1: Entries A-K’, Quarto Series,52, The Huguenot Society of London, (1977), Entry under BLANCHARD, Anne (1).

84 W.Minet and S. Minet (Edits.), Register of the Church at Hungerford Market, Quarto Series, Publications of The Huguenot Society of London, 31 (1928), p.49.

85 C.F.A. Marmoy, ‘Extracts from The Archives of La Providence 1718-1957 and 1745-1901 vol. II: Entries L-Z’, Quarto Series,53, The Huguenot Society of London (1977) p.13.

86 W. Minet and S. Minet (Edits), Registers of The Churches of The tabernacle Glasshouse Street and Leicester Fields 1688-1783, The Publications of The Huguenot Society of London, 29 (1925), p.161.

87 A.T. Carpenter, ‘J.T Desaguliers: An 18th Century Experimental Philosopher and Freemason’, The Huguenot Society Journal, 30 (No 4) (2016), 509.

88 P.M. Rambaut, ‘The Rambaut Family: astronomy and astronautics’, Proceedings of The Huguenot Society, 27 (No. 1) (1998), pp. 112-113.

Article by: Nigel Wade

Educated at The Stationers’ Company's School, and the University of London.

A regular writer for the school magazine and ‘The Old Stationer’; member of the Brentwood Writers’ Circle.

Nigel has written one children's book ‘City Fox’, and various articles for ‘The Square Magazine’.

Recent Articles: by Nigel Wade

Aleister Crowley - a very irregular Freemason Aleister Crowley, although made a Freemason in France, held a desire to be recognised as a 'regular' Freemason within the jurisdiction of UGLE – a goal that was never achieved. |

Sir Joseph Banks – The botanical Freemason Banks was also the first Freemason to set foot in Australia, who was at the time, on a combined Royal Navy & Royal Society scientific expedition to the South Pacific Ocean on HMS Endeavour led by Captain James Cook. |

Sir Arthur Sullivan - A Masonic Composer We are all familiar with the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, but did you know Sullivan was a Freemason, lets find out more…. |

The Much-Maligned Dr John Misaubin The reputation of the Huguenot Freemason, has been buffeted by waves of criticism for the best part of three hundred years. |

Who was Philip, Duke of Wharton and was he Freemasonry’s Loose Cannon Ball ? |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device