In 1915, Joseph Fort Newton’s book, ‘The Builders: A Story and Study of Freemasonry’ was published.

It has become a Masonic classic in as much that it really does lay the foundations of knowledge for us to build upon.

Taking us back to the times of the ‘builders’ before the traditional history of the Craft, he explores not only the history of man’s quest to build – both literally and figuratively – but how it relates to the speculative work of the Freemason.

His insights and wisdom are as relevant today as they were over a hundred years ago.

Extracted from The Builders: A Story and Study of Freemasonry

Joseph Fort Newton

The Torch Press, Iowa, 1915

And so the Quest goes on. And the Quest, as it may be, ends in attainment—we know not where and when: so long as we can conceive of our separate existence, the quest goes on—an attainment continued henceforward. And ever shall the study of the ways which have been followed by those who have passed in front be a help on our own path.

It is well, it is of all things beautiful and perfect, holy and high of all, to be conscious of the path which does in fine lead thither where. we seek to go, namely, the goal which is in God. Taking nothing with us which does not belong to ourselves, leaving nothing behind us that is of our real selves, we shall find in the great attainment that the companions of our toil are with us. And the place is the Valley of Peace.

— ARTHUR EDWARD WAITE, The Secret Tradition.

Chapter 3 – The Drama of Faith

MAN does not live by bread alone; he lives by Faith, Hope, and Love, and the first of these was Faith.

Nothing in the human story is more striking than the persistent, passionate, profound protest of man against death.

Even in the earliest time we see him daring to stand erect at the gates of the grave, disputing its verdict, refusing to let it have the last word, and making argument in behalf of his soul.

For Emerson, as for Addison, that fact alone was proof enough of immortality, as revealing a universal intuition of eternal life.

Others may not be so easily convinced, but no man who has the heart of a man can fail to be impressed by the ancient, heroic faith of his race.

The Three Graces – Faith, Hope and Charity.

IMAGE LINKED: An Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry, Albert G. Mackey, Masonic History Company, Chicago, 1924

Nowhere has this faith ever been more vivid or victorious than among the old Egyptians. In the ancient Book of the Dead [aka The Book of Coming Forth by Day] —which is, indeed, a Book of Resurrection—occur the words: “The soul to heaven; the body to earth”; and that first faith is our faith today.

Of King Unas, who lived in the third millennium, it is written: “Behold, thou hast not gone as one dead, but as one living”.

Nor has any one in our day set forth this faith with more simple eloquence than the Hymn to Osiris, in the Papyrus of Hunefer.

So in the Pyramid Texts the dead are spoken of as Those Who Ascend, the Imperishable Ones who shine as stars, and the gods are invoked to witness the death of the King “Dawning as a Soul”.

The burial chamber of Unas’ pyramid at Saqqara, with spells from the Book of the Dead – King Unas (ninth\last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty) was the first pharaoh to have the Pyramid Texts depicted within his tomb. By Jon Bodsworth – egyptarchive.co.uk

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

There is deep prophecy, albeit touched with poignant pathos, in these broken exclamations written on the pyramid walls:

Thou diest not! Have ye said that he would die?

He diest not; this King Pepi lives forever! Live! Thou shalt not die! He has escaped his day of death! Thou livest, thou livest, raise thee up!

Thou diest not, stand up, raise thee up! Thou perishest not eternally! Thou diest not!

Nevertheless, nor poetry nor chant nor solemn ritual could make death other than death; and the pyramid Texts, while refusing to utter the fatal word, give wistful reminiscences of that blessed age “before death came forth.”

However high the faith of man, the masterful negation and collapse of the body was a fact, and it was to keep that daring faith alive and aglow that The Mysteries were instituted.

Beginning, it may be, in incantation, they rose to heights of influence and beauty, giving dramatic portrayal of the unconquerable faith of man.

Watching the sun rise from the tomb of night, and the spring return in glory after the death of winter, man reasoned from analogy—justifying a faith that held him as truly as he held it—that the race, sinking into the grave, would rise triumphant over death.

Kneeling Statuette of Pepy I, ca. 2338-2298 B.C.E. Greywacke, alabaster, obsidian, copper, 6 x 1 13/16 x 3 9/16 in. (15.2 x 4.6 x 9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 39.121.

IMAGE LINKED: Brooklyn Museum, Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

I

There were many variations on this theme as the drama of faith evolved, and as it passed from land to land; but the Motif was ever the same, and they all were derived, directly or indirectly, from the old Osirian passion-play in Egypt.

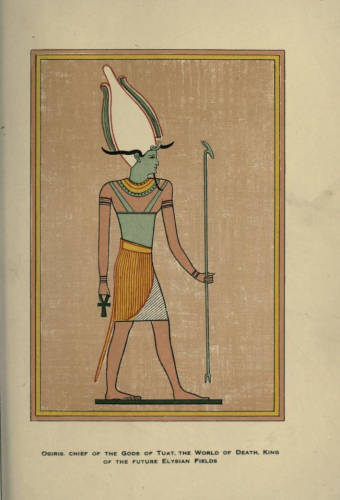

Against the back-ground of the ancient Solar religion, Osiris made his advent as Lord of the Nile and fecund Spirit of vegetable life—son of Nut the sky-goddess and Geb the earth-god; and nothing in the story of the Nile-dwellers is more appealing than his conquest of the hearts of the people against all odds.

Howbeit, that history need not detain us here, except to say that by the time his passion had become the drama of national faith, it had been bathed in all the tender hues of human life; though somewhat of its solar radiance still lingered in it.

Enough to say that of all the gods, called into being by the hopes and fears of men who dwelt in times of yore on the banks of the Nile, Osiris was the most beloved.

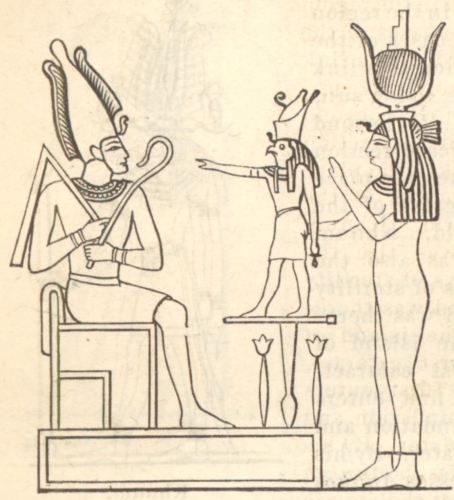

Osiris the benign father, Isis his sorrowful and faithful wife, and Horus whose filial piety and heroism shine like diamonds in a heap of stones—about this trinity were woven the ideals of Egyptian faith and family life.

Hear now the story of the oldest drama of the race, which for more than three thousand years held captive the hearts of men.

The ancient Egyptian mythological Trinity or Triad: Osiris, Horus and Isis.

Baedeker, Karl. Egypt, Handbook for Traveling, pt.1 Lower Egypt, with the Fayum and the peninsula of Sinai. K. Baedeker, Leipsic, 1885. p. 130.

IMAGE LINKED: Baedeker, Karl. Egypt, Handbook for Traveling

Osiris was Ruler of Eternity, but by reason of his visible shape seemed nearly akin to man—revealing a divine humanity.

His success was chiefly due, however, to the gracious speech of Isis, his sister-wife, whose charm men could neither reckon nor resist.

Together they labored for the good of man, teaching him to discern the plants fit for food, themselves pressing the grapes and drinking the first cup of wine.

They made known the veins of metal running through the earth, of which man was ignorant, and taught him to make weapons.

They initiated man into the intellectual and moral life, taught him ethics and religion, how to read the starry sky, song and dance and the rhythm of music.

Above all, they evoked in men a sense of immortality, of a destiny beyond the tomb. Nevertheless, they had enemies at once stupid and cunning, keen-witted but short-sighted—the dark force of evil which still weaves the fringe of crime on the borders of human life.

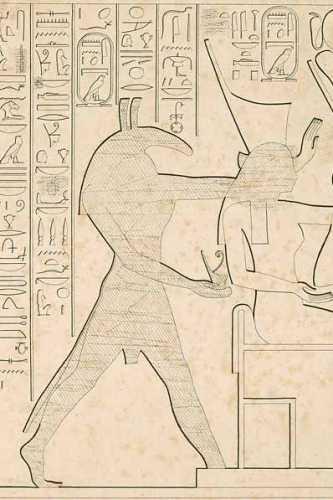

Closeup of a drawing of an ancient Egyptian relief depicting the god Seth praising the High priest of Amun Herihor Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84) – Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien – Abth. III, Band VIII, pl. 246.

IMAGE LINKED: Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien

Side by side with Osiris, lived the impious Set-Typhon, as Evil ever haunts the Good.

While Osiris was absent, [Set] Typhon—whose name means serpent—filled with envy and malice, sought to usurp his throne; but his plot was frustrated by Isis.

Whereupon he resolved to kill Osiris. This he did, having invited him to a feast, by persuading him to enter a chest, offering, as if in jest, to pre-sent the richly carved chest to any one of his guests who, lying down inside it, found he was of the same size.

When Osiris got in and stretched himself out, the conspirators closed the chest, and flung it into the Nile. Thus far, the gods had not known death.

They had grown old, with white hair and trembling limbs, but old age had not led to death.

As soon as Isis heard of this infernal treachery, she cut her hair, clad herself in a garb of mourning, ran thither and yon, a prey to the most cruel anguish, seeking the body.

Weeping and distracted, she never tarried, never tired in her sorrowful quest.

Mourning Isis, Ptolemaic Period 332-3-BC.

IMAGE LINKED: Met Museum Open Access Licence

Meanwhile, the waters carried the chest out to sea, as far as Byblos in Syria, the town of Adonis, where it lodged against a shrub of arica, or tamarisk—like an acacia tree.

Owing to the virtue of the body, the shrub, at its touch, shot up into a tree, growing around it, and protecting it, until the king of that country cut the tree which hid the chest in its bosom, and made from it a column for his palace.

At last Isis, led by a vision, came to Byblos, made herself known, and asked for the column.

Hence the picture of her weeping over a broken column torn from the palace, while Horus, god of Time, stands behind her pouring ambrosia on her hair.

She took the body back to Egypt, to the city of Bouto; but Typhon, hunting by moonlight, found the chest, and having recognized the body of Osiris, mangled it and scattered it beyond recognition.

Isis, embodiment of the old world-sorrow for the dead, continued her pathetic quest, gathering piece by piece the body of her dismembered husband, and giving him decent interment.

Such was the life and death of Osiris, but as his career pictured the cycle of nature, it could not of course end here.

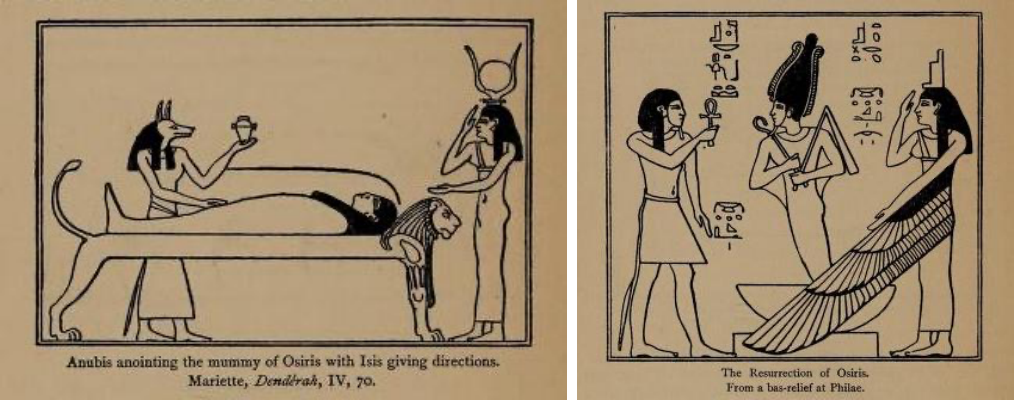

Osiris & the Egyptian Resurrection.

IMAGE LINKED: E. A. Wallis Budge, Warner, London, 1911. Public Domain.

Horus fought with Typhon, losing an eye in the battle, but finally overthrew him and took him prisoner.

There are several versions of his fate, but he seems to have been tried, sentenced, and executed—”cut in three pieces,” as the Pyramid Texts relate.

Thereupon the faithful son went in solemn procession to the grave of his father, opened it, and called upon Osiris to rise: “Stand up! Thou shalt not end, thou shalt not perish!” But death was deaf.

Here the Pyramid Texts recite the mortuary ritual, with its hymns and chants; but in vain.

At length Osiris awakes, weary and feeble, and by the aid of the strong grip of the lion-god he gains control of his body, and is lifted from death to life.

Thereafter, by virtue of his victory over death, Osiris becomes Lord of the Land of Death, his scepter and Ank [sic] Cross, his throne a Square.

The sacred books and early literature of the East; with an historical survey and descriptions.

IMAGE LINKED: Charles Francis Horne, Parke, New York, 1917. Public Domain.

II

Such, in brief, was the ancient allegory of eternal life, upon which there were many elaborations as the drama unfolded; but always, under whatever variation of local color, of national accent or emphasis, its central theme remained the same.

Often perverted and abused, it was everywhere a dramatic expression of the great human aspiration for triumph over death and union with God, and the belief in the ultimate victory of Good over Evil.

Not otherwise would this drama have held the hearts of men through long ages, and won the eulogiums of the most enlightened men of antiquity—of Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, Euripides, Plutarch, Pindar, Isocrates, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius.

Writing to his wife after the loss of their little girl, Plutarch commends to her the hope set forth in the mystic rites and symbols of this drama, as, elsewhere, he testifies that it kept him “as far from superstition as from atheism,” and helped him to approach the truth.

For deeper minds this drama had a double meaning, teaching not only immortality after death, but the awakening of man upon earth from animalism to a life of purity, justice, and honor.

How nobly this practical aspect was taught, and with what fineness of spiritual insight, may be seen in Secret Sermon on the Mountain in the Hermetic lore of Greece:

What may I say, my son? I can but tell thee this.

Whenever I see within myself the Simple Vision brought to birth out of God’s mercy, I have passed through myself into a Body that can never die.

Then I am not what I was before… They who are thus born are children of a Divine race.

This race, my son, is never taught; but when He willeth it, its memory is restored by God.

It is the “Way of Birth in God.” Withdraw into thyself and it will come. Will, and it comes to pass.

Isis herself is said to have established the first temple of the Mysteries, the oldest being those practiced at Memphis [Egypt].

Of these there were two orders, the Lesser to which the many were eligible, and which consisted of dialogue and ritual, with certain signs, tokens, grips, passwords; and the Greater, reserved for the few who approved themselves worthy of being entrusted with the highest secrets of science, philosophy, and religion.

For these the candidate had to undergo trial, purification, danger, austere asceticism, and, at last, regeneration through dramatic death amid rejoicing.

Such as endured the ordeal with valor were then taught, orally and by symbol, the highest wisdom to which man had attained, including geometry, astronomy, the fine arts, the laws of nature, as well as the truths of faith.

Awful oaths of secrecy were exacted, and Plutarch describes a man kneeling, his hands bound, a cord round his body, and a knife at his throat—death being the penalty of violating the obligation.

Even then, Pythagoras had to wait almost twenty years to learn the hidden wisdom of Egypt, so cautious were they of candidates, especially of foreigners.

But he made noble use of it when, later, he founded a secret order of his own at Crotona, in Greece, in which, among other things, he taught geometry, using numbers as symbols of spiritual truth.

Worshipping of the sarcophagus of Osiris – a depiction on a fresco in the Temple of Isis at Pompeii, 1 AD. Unknown artist.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

From Egypt the Mysteries passed with little change to Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome, the names of local gods being substituted for those of Osiris and Isis.

The Grecian or Eleusinian Mysteries, established 1800 B. C., represented Demeter and Persephone, and depicted the death of Dionysius with stately ritual which led the neophyte from death into life and immortality.

They taught the unity of God, the immutable necessity of morality, and a life after death, investing initiates with signs and passwords by which they could know each other in the dark as well as in the light.

The Mithraic or Persian Mysteries celebrated the eclipse of the Sun-god, using the signs of the zodiac, the processions of the seasons, the death of nature, and the birth of spring.

The Adoniac or Syrian cults were similar, Adonis being killed, but revived to point to life through death. In the Cabirie [Cabeiri] Mysteries on the island of Samothrace, Atys the Sun was killed by his brothers the Seasons, and at the vernal equinox was restored to life.

An imaginative illustration of a ‘An Arch Druid in His Judicial Habit’ from The Costume of the Original Inhabitants of the British Islands by S.R. Meyrick and C.H. Smith (1815).

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

So, also, the Druids, as far north as England, taught of one God the tragedy of winter and summer, and conducted the initiate through the valley of death to life everlasting.

Shortly before the Christian era, when faith was failing and the world seemed reeling to its ruin, there was a great revival of the Mystery-religions. Imperial edict was powerless to stay it, much less stop it.

From Egypt, from the far East, they came rushing in like a tide, Isis “of the myriad names” vying with Mithra, the patron saint of the soldier, for the homage of the multitude.

If we ask the secret reason for this influx of mysticism, no single answer can be given to the question. What influence the reigning mystery-cults had upon the new, uprising Christianity is also hard to know, and the issue is still in debate.

That they did influence the early Church is evident from the writings of the Fathers, and some go so far as to say that the Mysteries died at last only to live again in the ritual of the Church. St. Paul in his missionary journeys came in contact with the Mysteries, and even makes use of some of their technical terms in his epistles but he condemned them on the ground that what they sought to teach in drama can be known only by spiritual experience—a sound insight, though surely drama may assist to that experience, else public worship might also come under ban.

III

Toward the end of their power, the Mysteries fell into the mire and became corrupt, as all things human are apt to do: even the Church itself being no exception.

But that at their highest and best they were not only lofty and noble, but elevating and refining, there can be no doubt, and that they served a high purpose is equally clear.

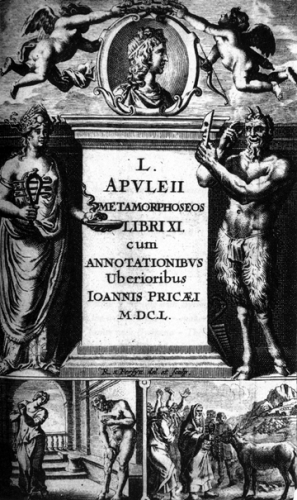

No one, who has read in the Metamorphoses of Apuleius the initiation of Lucius into the Mysteries of Isis, can doubt that the effect on the votary was profound and purifying. He tells us that the ceremony of initiation “is, as it were, to suffer death”, and that he stood in the presence of the gods, “ay, stood near and worshiped”.

Far hence ye profane, and all who are polluted by sin, was the motto of the Mysteries, and Cicero testifies that what a man learned in the house of the hidden place made him want to live nobly, and gave him happy hopes for the hour of death.

Title page from John Price’s Latin edition of Apuleius’ novel “Metamorphoses, or the Golden Ass” (Gouda, Netherlands, 1650).

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Indeed, the Mysteries, as Plato said were established by men of great genius who, in the early ages, strove to teach purity, to ameliorate the cruelty of the race, to refine its manners and morals, and to restrain society by stronger bonds than those which human laws impose.

No mystery any longer attaches to what they taught, but only as to the particular rites, dramas, and symbols used in their teaching.

They taught faith in the unity and spirituality of God, the sovereign authority of the moral law, heroic purity of soul, austere discipline of character, and the hope of a life beyond the tomb.

Thus, in ages of darkness, of complexity, of conflicting peoples, tongues, and faiths, these great orders toiled on behalf of friendship, bringing men together under a banner of faith, and training them for a nobler moral life.

Tender and tolerant of all faiths, they formed an all-embracing moral and spiritual fellowship which rose above barriers of nation, race, and creed, satisfying the craving of men for unity, while evoking in them a sense of that eternal mysticism out of which all religions were born.

Their ceremonies, so far as we know them, were stately dramas of the moral life and the fate of the soul.

Mystery and secrecy added impressiveness, and fable and enigma disguised in imposing spectacle the laws of justice, piety, and the hope of immortality.

A depiction of a Phoenix – symbolic of immortality and resurrection. From an engraving by Friedrich Justin Bertuch, 1806

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Masonry stands in this tradition; and if we may not say that it is historically related to the great ancient orders, it is their spiritual descendant, and renders much the same ministry to our age which the Mysteries rendered to the olden world.

It is, indeed, the same stream of sweetness and light flowing in our day—like the fabled river Alpheus which, gathering the waters of a hundred rills along the hillsides of Arcadia, sank, lost to sight, in a chasm in the earth, only to reappear in the fountain of Arethusa.

This at least is true: the Greater Ancient Mysteries were prophetic of Masonry whose drama is an epitome of universal initiation, and whose simple symbols are the depositaries of the noblest wisdom of mankind.

As such, it brings men together at the altar of prayer, keeps alive the truths that make us men, seeking, by every resource of art, to make tangible the power of love, the worth of beauty, and the reality of the ideal.

Article by: Joseph Fort Newton

Rev. Newton (1880–1950) , was an American Baptist minister, authored a number of masonic books, including his best-known works, The Builders, published in 1914, and The Men’s House, published in 1923.

He received the third degree of Freemasonry on May 28, 1902 in Friendship Lodge No. 7, Dixon, Illinois, later affiliating with Mt. Hermon Lodge No. 263, Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

He also served as Grand Chaplain of the Grand Lodge of Iowa from 1911 to 1913 and Grand Prelate of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar.

The Builders has been called "an outstanding classic in Masonic literature offering the early history of Freemasonry."

The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts

By: James. P. Allen

James P. Allen provides a translation of the oldest corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts from the six royal pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties (ca. 2350-2150 BCE). Allen s revisions take into account recent advances in the understanding of Egyptian grammar.

Features:

• Sequential translations based on all available sources, including texts newly discovered in the last decade

• Texts numbered according to the most widely used numbering system with new numbers from the latest 2013 concordance

• Translations reflect the primarily atemporal verbal system of Old Egyptian, which conveys the timeless quality that the text s authors understood the texts to have

The Egyptian Book of the Dead

By: Wallace Budge (Translator, Commentary), John Romer (Introduction)

Consisting of spells, prayers and incantations, each section contains the words of power to overcome obstacles in the afterlife.

The papyruses were often left in sarcophagi for the dead to use as passports on their journey from burial, and were full of advice about the ferrymen, gods and kings they would meet on the way.

Offering valuable insights into ancient Egypt, The Book of the Dead has also inspired fascination with the occult and the afterlife in recent years.

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,700 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines.

Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

On Isis and Osiris

By: Plutarch (Author)

The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences.

Osiris’s murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris’s wife Isis restores her husband’s body, allowing him to posthumously conceive a son with her. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set’s rival for the throne.

Their often violent conflict ends with Horus’s triumph, which restores order to Egypt after Set’s unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris’s resurrection. The myth, with its complex symbolism, is integral to the Egyptian conceptions of kingship and succession, conflict between order and disorder, and especially death and the afterlife.

It also expresses the essential character of each of the four deities at its center, and many elements of their worship in ancient Egyptian religion were derived from the myth. The Osiris myth reached its basic form in or before the 24th century BCE.

Many of its elements originated in religious ideas, but the struggle between Horus and Set may have been partly inspired by a regional conflict in Egypt’s early history or prehistory. Scholars have tried to discern the exact nature of the events that gave rise to the story, but they have reached no definitive conclusions. Parts of the myth appear in a wide variety of Egyptian texts, from funerary texts and magical spells to short stories.

The story is, therefore, more detailed and more cohesive than any other ancient Egyptian myth. Yet no Egyptian source gives a full account of the myth, and the sources vary widely in their versions of events. Greek and Roman writings, particularly De Iside et Osiride by Plutarch, provide more information but may not always accurately reflect Egyptian beliefs.

Through these writings, the Osiris myth persisted after knowledge of most ancient Egyptian beliefs was lost, and it is still well known today.

The Secret Teachings of All Ages: An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy

By: Manly P. Hall

This key to the world’s esoteric traditions unlocks some of the most fascinating and closely held secrets of myth, religion, and philosophy. Unrivaled in its beauty and completeness, it distills ancient and modern teachings of nearly 600 experts.

Compelling themes range from the riddle of the Sphinx and the tenets of Pythagorean astronomy to the symbolism of the pentagram, the significance of the Ark of the Covenant, and the design of the American flag.

Acclaimed by Publishers Weekly as “a classic reference, dizzying in its breadth,” this remarkable resource was compiled by the founder of the Philosophical Research Society. Author Manly P. Hall examines the secrets of Isis along with arcane aspects of mystic Christianity and other religions.

Fascinating surveys cover topics as diverse as Kabbalah, alchemy, cryptology, and Tarot, along with Masonry, gemology, and the identity of William Shakespeare. Sixteen pages of color plates and 100 black-and-white images by the celebrated illustrator J. Augustus Knapp illuminate this vast and indispensable encyclopedia of the occult.

Recent Articles: The Builders by Joseph Fort Newton

The Builders – 1 The Foundations Chapter 1. The Foundations Explore an outstanding classic in Masonic literature - an exposition of the early history and symbolism of Freemasonry – from the foundations upwards. |

The Builders – 2 The Working Tools Chapter 2. The Working Tools - Explore an outstanding classic in Masonic literature - an exposition of the early history and symbolism of Freemasonry – from the foundations upwards. |

The Builders – 3 The Drama of Faith Chapter 3. The Drama of Faith - Explore an outstanding classic in Masonic literature - an exposition of the early history and symbolism of Freemasonry – from the foundations upwards. |

The Builders – 4 The Secret Doctrine Chapter 4. The Secret Doctrine - Explore an outstanding classic in Masonic literature - an exposition of the early history and symbolism of Freemasonry – from the foundations upwards. By Joseph Fort Newton |

Chapter 5. The Collegia - If the laws of building were secrets known only to initiates, there must have been a secret Order of architects who built the temple of Solomon. Who were they? |

The Builders – 6 The Free-Masons Chapter 6. the Free-Masons - an examination into the history of the medieval guilds, their charges and regulations that form the base for the allegories and symbols in our modern versions of masonic craft ritual. By Joseph Fort Newton |

Chapter 7. the Fellowcrafts - an examination into the history of the medieval guilds, their charges and regulations that form the base for the allegories and symbols in our modern versions of masonic craft ritual. By Joseph Fort Newton |

The Builders – 8 Accepted Masons Chapter 8. Accepted Masons - an examination into the history of accepted masons, and why did soldiers, scholars, antiquarians, clergymen, lawyers, and even the nobility ask to be accepted as members of the order of Free-masons? By Joseph Fort Newton |

The Builders – 9 Grand Lodge of England Chapter 9. Grand Lodge of England - From every point of view, the organization of the Grand Lodge of England, in 1717, was a significant and far-reaching event. By Joseph Fort Newton |

The Builders – 10 Universal Masonry Chapter 10. Universal Masonry - Henceforth, the Masons of England were no longer a society of handicraftsmen, but an association of men of all orders and every vocation, as also of almost every creed, |

The Builders – 11 What is Masonry Chapter 11 "Masonry is the activity of closely united men who, employing symbolical forms borrowed principally from the mason's trade and from architecture, work for the welfare of mankind, striving morally to ennoble themselves and others, and thereby to bring about a universal league of mankind, which they aspire to exhibit even now on a small scale." |

The Builders – 12 The Masonic Philosophy Chapter 12 When we look at Masonry in this large and mellow light, it is like a stately old cathedral, gray with age, rich in associations, its steps worn by innumerable feet of the living and the dead—not piteous, but strong and enduring. By Joseph Fort Newton |

The Builders – 13 The Spirit of Masonry Chapter 13 Masonry is Friendship—friendship, first, with the great Companion, of whom our own hearts tell us, who is always nearer to us than we are to our-selves, and whose inspiration and help is the greatest fact of human experience. |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device