Further to my article on the Workers’ Village at Deir el Medina that existed in ancient Egypt, I have been researching the use of identification marks and other possible parallels to medieval stonemasons and subsequently the Free-masons.

During this research I discovered that many of the Guilds and their members used ‘secret languages’, known as ‘argots’, ‘cants’, or the ‘bine’.

What fascinated me more was the origin of such languages, which include a broad smattering of dialects from across the globe.

Egypt’s ‘Place of Truth’ – The First Operative Stone Masons’ Guild?

Was ancient Egypt’s ‘village of the artisans’ the first operative stone masons’ guild? And was their use of ‘identity marks’ a forerunner of the Mason’s Marks of the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages? Read on for some possible answers…

more….

Linguistics – the scientific study of human language – is complex and involves a comprehensive, systematic, and precise study, encompassing the analysis of all aspects.

I recently began to study the linguistics of the dead ancient Egyptian language, of which the closest extant remains are to be found in Coptic.

Therefore, I understood just how complicated the process can be – taking into account stylistics, morphology, phonetics, syntax, rhetoric, utterance and translation.

The study of formal language began in India in the 6th century BC when grammarian Pāṇini formulated 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology.

Pāṇini’s systematic classification of the sounds of Sanskrit into consonants and vowels, and word classes, such as nouns and verbs. It was the first known instance of its kind.

In the Middle East, Sibawayh, a Persian, made a detailed description of Arabic in AD 760 in his monumental work, Al-kitab fii an-naħw (الكتاب في النحو, The Book on Grammar), the first known author to distinguish between sounds and phonology. [1]

A representational statue of Pāṇini at Panini Tapobhumi, Arghakhanchi District of Nepal

By Panini Khabar – https://twitter.com/paninikhabar

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Argots, Cants, and Jargons

So, where did the language of the Guilds originate? It appears that many of the Trade Guilds employed argots – it was a way of not only keeping the secrets of their trade from eavesdroppers or competing workmen but also as a way of making sure their employers didn’t understand what they were discussing.

Here are the definitions of ‘cant’, ‘argot’ and ‘jargon’:

A cant is the jargon or language of a group, often employed to exclude or mislead people outside the group.

An argot is a language used by various groups to prevent outsiders from understanding their conversations. The term ‘argot’ is also used to refer to the informal specialized vocabulary from a particular field of study, occupation, or hobby, in which sense it overlaps with jargon.

Jargon is the specialized terminology associated with a particular field or area of activity. Jargon is normally employed in a particular communicative context and may not be well understood outside that context. The context is usually a particular occupation (that is, a certain trade, profession, vernacular or academic field), but any ingroup can have jargon.

The main trait that distinguishes jargon from the rest of a language is special vocabulary—including some words specific to it and often different senses or meanings of words, that outgroups would tend to take in another sense—therefore misunderstanding that communication attempt.

Jargon is sometimes understood as a form of technical slang and then distinguished from the official terminology used in a particular field of activity.

– Source: Wikipedia

There are five known masons’ argots still in circulation; they are dying languages but are being preserved by a few historical groups, including the Stonemasons’ Guild of St Stephen and St George, based in the city of Norwich, England.

Their website offers a unique glimpse into the various argots, and was of huge use to me when researching this article.

Summa Inter Mediocria – The logo and motto of The Stonemasons’ Guild of St Stephen and St George

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The languages are:

Bearla Lagair Na Saor (Bearla Lagair) – a language used primarily by Irish stonemasons or those from the Low Countries

Bearlish – the argot used by the Guild Master and his contemporaries

Mourmé – the secret language of the masons of Samoëns

Latín dos canteiros or verbo dos arginas (‘Latin of the stonecutters’) – the argot of stone cutters/masons in Galicia, Spain.

Mastorika also known as Koudaritika – used by the stonemasons from Greece and Macedonia. Koudaritika was primarily used by the guild workers in the north-western region of Epirus.

There was also a secret language known as Boliarika, which was actively used until the 1960s by groups of professional tradesmen, or ‘Boliarides’, who were nomadic groups who earned their living by travelling across the mountainous area of Nafpaktia in Greece, practising their crafts.

Dr Kakia Chatsiou from SOAS University, London has researched this declining language and her data demonstrates how the language is an amalgam of Greek, Bulgarian, Romanian, and Turkish – all dialects in the countries the Boliarides traded with. You can see her lecture from 2014, entitled ‘Adventures with Boliarika: documenting an endangered secret trade language of Central Greece‘

The Mason’s Argots

Bearla Lagair Na Saor (Bearla Lagair)

According to the Stonemasons’ Guild of St. Stephen and St. George :

‘Bearla Lagair Na Saor (shortened to Bearla Lagair) or Masons’ gibberish is a secret language (cant) used by stonemasons, mainly in Ireland and The Low Countries.

It was still in regular use in The UK and Ireland up until the 1980s although there are stonemasons who still hold and use the language today and The Guild has direct connections with some of these individuals.

Bearlish, the distinct argot spoken by the Guild Master and his contemporaries is rooted primarily in Bearla Lagair Na Saor.

Speakers of Bearla Lagair, as with Bearlish, do not use the name of the argot, referring to it instead as the ‘bine’ (masons’ talk or mason language).’

[via https://www.stonemasonsguild.org/bearla-lagair-na-saor]

Albert Thomas Sinclair was a lawyer from Boston, Massachusetts who had a fascination with the study of gypsies, their lifestyle, culture, and language.

He wrote several books on the subject and contributed to various Journals, and corresponded with Archduke Joseph Karl of Austria, who held a similar interest in the Romani language.

In a biography of Sinclair, there is mention that the Archduke sent him a copy of his work, ‘a large octavo volume handsomely bound.

It is a most important and valuable philological work comparing the gypsy words with Sanskrit, Hindustani Persian, etc’. [2]

Below is an extract from ‘The Secret Language of Masons and Tinkers’ by A. T. Sinclair, originally published in The Journal of American Folklore, 1909. [3]

On mentioning the subject to some old Irish masons here in Allston, I was surprised to find they could speak this language which they called “Bearla lagair na saor;” and what interested me, perhaps even more, was the fact that they had a mass of folk-tales and traditions connected with their craft and with Gobán Saor the bard mason, who, they say, founded this talk.

At first I was very incredulous, for I was well aware of the exuberance of the imaginations of many of the Celtic race; but I found that over a dozen of these masons, unacquainted with each other and questioned independently, all told exactly the same stories and full details.

In addition to this, a large number of other old Irishmen knew there was such a mason’s talk called “Bearla lagair,” and many of these same traditions and folk-tales.

It is clear that such was common knowledge among large numbers in Ireland.

This mason’s talk is a secret language spoken only by stone-masons, they all claim.

Apprentices obtained from a master-mason first papers, second papers, and finally a third paper, called an “indenture,” and an increase of wages with each paper.

No apprentice was entitled to his indenture until he could speak the “ Bearla lagair.”

They were forbidden to teach it to any one not a mason, even to a member of their own family.

No stone-mason would work on any job except with members of the order. This language identified them.

They also had secret signs, methods of handling their trowels, squares, and other tools, ways of pointing, and laying and smoothing mortar, which indicated a member, without a word being spoken.

Meetings were held, from which strangers were excluded by posted sentinels. Any member who had broken a rule of the craft could be tried and punished. Some of these rules were designed to protect the health; and the tradition is, that in olden times masons had the right to, and did, punish occasionally with the death penalty.

They were a powerful order, and at that time contained a large class of the most intelligent men of the time. The mason’s trade was perhaps the most important craft.

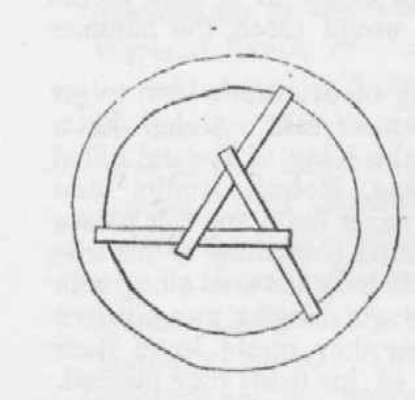

Sometimes a love of adventure led the Gobán Saor to wander incognito as a common workman.

His renown as an architect and artistic sculptor was widespread. One simple story which amuses these workingmen is this. The Gobán Saor once, in a foreign land, applied to the master- builder of a cathedral for work.

“What can you do?”asked the master. “Try me and see,” was the laconic reply.

Then the builder placed him in a work-shed alone by himself, and, pointing to a block of stone, said facetiously, “Carve from that a cat with two tails.”

The shed was fasttened at night, and the next morning Gobán had disappeared.

When the master unfastened the shed and looked in, he found that the block of stone had been most beautifully carved into a cat with two tails.

With an exclamation of surprise, he ejaculated, “It was the Gobán Saor himself! No other human being could do such superb work, or so quickly.”

The mason’s mark or symbol, associated with An Gobán Saor; the cat with two tails. Via kildarenow.com

Professor Meyer and Mr. Sampson have abundantly shown that Shelta, the tinker’s jargon, is mostly an artificial language formed from very old Irish.

Some of it is back slang; also syllables are prefixed, added, inserted in a word, and various other artifices are resorted to.

The Bearla lagair, or mason’s talk, is plainly founded on the same Old-Irish, but has a very large number of its words not disguised.

The number of words for one thing is often very large. My conclusion is that both talks are the same, except that the masons use a very much larger proportion of undisguised Old-Irish words in their ordinary conversation.

Some words used by Shakespeare, and marked in the Century Dictionary as “origin unknown,” are found in Shelta, or mason’s talk.

Leland remarks, “Shakespeare, who knew everything, makes Prince Hal declare that he could drink with a tinker in his own language.

Bearlish

This was the argot spoken by the Guild Master and his contemporaries and is rooted primarily in Bearla Lagair, it appears more cosmopolitan since it was developed around London.

According to the Stonemason’s Guild of St Stephen and St George, ‘it is not an argot used by rural rough masons but rather by Free or Court Masons.

Although the argot name is not used, and it is instead always referred to as the ‘bine’ (masons’ talk or mason language)’ and for all purposes they call it ‘Bearlish’.

The roots of the language are far reaching and include (not exhaustive) those dialects from the French Regional, Brittonic (Breton, Cornish, Welsh), Goidelic (Irish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic), Shelta, Bungee, Old Saxon, German, Norse, Anglo-French, Eastern (Thug, Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Turkish, Romani) and African (Berber, Zulu etc.)

The Guild states that Bearlish is primarily an oral traditional language and should not be written down, but they have the full lexicon on their page, which is fascinating, you can access it here: [https://www.stonemasonsguild.org/bearlish]

To learn how to count 1-10 in Bearlish, click on the link [https://www.stonemasonsguild.org/counting-in-bearlish]

Mourmé

A general view of Samoëns. By Christophe Martin – own canon camera, Public Domain,

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Another argot used by the stone masons in Samoëns, a commune from the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of France was known as Mourmé:

Stone has long been a traditional feature of the Upper Giffre Valley which is dotted with limestone quarries (hardness coefficient, 13). To supplement their income from farming, the men in the region used to work stone.

In 1659, there were so many frahans (the local name for stone cutters and masons) in Samoëns and their expertise was so well known that they set up a very famous brotherhood. It engaged in charity work, taking care of the sick and training young apprentices in its own school of draughtsmen, which had an extensive library.

The members of the brotherhood of masons and stone cutters in Samoëns were contacted for leading construction projects. They worked with Vauban on his fortifications, were commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte to build canals in Saint-Quentin, and worked in Givors and even further afield, in Poland, Louisiana and Australia. To ensure that they were not understood by outsiders when talking to each other, they used their own dialect, called Mourmé.

– Source: Wikipedia

Latín Dos Canteiros

Morrón: pra cubicar muriar xidavante da argina xeres interbar o verbo das arginas xejorrumeando explicas es deeglase dadellastadaria e xeras enenvestar moxe xido…

Boy, if you want to practise the job as a stone breaker well you have to know the language in which the laws of how to cut stone are explained…

Latín dos canteiros (“Latin of the stonecutters”) or verbo dos arginas is the argot based on the Galician language, which was employed by Spanish stonemasons in Galicia, particularly in the area of Pontevedra. They handed down their knowledge by means of the secret language to the next generation.

– Source: Wikipedia

Javier Fdez-Catuxo on his blog Supraterram, has a fascinating article about the ‘Latin of the Stonecutters’ and their history:

Galician stonemasons, masters in the art of working stone, have long moved throughout the north of the peninsula in small groups that toured the towns, offering to build and carry out all kinds of works.

They spent long periods in each area, living full board (a mantido) in the clients’ houses and moving from town to town.

The use of the Latin dos canteiros in the Galician areas where this language originated is more than well known, but in the limits of Asturias and Galicia, it had not been documented until now.

In these areas, the oldest remember with grace and strangeness the Galician stonemasons speaking in their particular jargon, which they sometimes referred to as falar en xefra.

Below is a sample of text from linguist Julio Ballesteros Curiel’s work ‘Verbo das arginas. Jerga-latín de los canteros’:

In latín dos canteiros |

English translation |

|---|---|

Morrón: pra cubicar muriar xidavante da argina, |

Boy, if you want to practise the job as a stone breaker well, |

xeres interbar o verbo das arginas xejorrumeando explicas es deeglase dadellastadaria e xeras enenvestar moxe xido. |

you have to know the language in which the laws of how to cut stone are explained […]. |

Cando anisques solóte polo deundo a murriar como artina, |

When you go out into the world alone to work as a stone breaker, |

xera jalrruar toi compinches o nobis verbo |

you will talk to your job comrades in our language, |

si xeres te ormeando aprecio os do gichoficienes |

if you want to be esteemed by them |

e nente de xerian perreamente os lapingos e buxos. |

and not be treated badly by the masters and misters. |

Xilón, nexo agiote; |

Boy, you will not be a thief, |

xilón, nexo chumar; |

boy, you will not be a drinker, |

xilón, nexo esqueirar; |

boy, you will not be a liar; |

xilón, xido cabancar; |

boy, you will be well doing; |

xilón, xido entileger; |

boy, you will be taught; |

xilón, xido vay; |

boy, you will be true. |

xilón, xido murriar. |

boy, you will be a worker.” |

– Source: Wikipedia

Stone monument from Beariz with a poem by Xesús Antonio Gulías Lamas in the cant. By Martinho12 – Feito por min, GFDL,

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Mastorika

Vouzios mi xyflias, touliz ‘ou baros= Silence, do not speak, the boss is listening

Mastorika – or Koudaritika – was the distinctive argot used by the stonemasons from Greece and Macedonia. Koudaritika was primarily used by the guild workers in the north-western region of Epirus.

Some of the villages, particularly Kastanea, Pyrsoyianni and Drosopigi, have retained their traditional character created in the past via the master craftsmen of the region, including stonemasons, the artists and iconographers of Hioniades and the sculptors of Playia.

Speaking their own dialect, Koudaritika, and governed by a strict hierarchy, they once traveled all over the Balkans and mainland Greece building schools, monasteries, hammams, mosques, manor houses, lighthouses and mills.

The stone bridges, some of which are over 100 years old, are perhaps the most impressive monuments to a craft that has now died out.

Emigration that began at the end of the 18th century and peaked during wartime took the craftsmen away to the far ends of the earth in search of a better future.

– Source: https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/49095/retaining-tradition-only-hope-for-future/

Ronald Walkey, in ‘A Lesson in Continuity: The Legacy of the Builders’ Guild in Northern Greece’ (Dwelling, Seeing and Designing, 1993, p.40) gives an insight into the purposes of the argot:

The inner cohesion of the bouloukia and the isnaf was reinforced by the fact that they had developed an argot.

This secret language of the builders, mastorika or koudarika in Greek, served several purposes. It immediately set the group apart and claim edits members’ allegiance, almost like a uniform.

It also enabled each boulouki to protect its craft secrets. As other non-building villages gained wealth and had the means to initiate their own local building industry, it was important that the house-building skills be held within the guild to protect their livelihood.

Finally, this secrecy was important for self-defence. Sometimes builders were targets of local extortion, or they would be working so far from home that some animosity might arise with the local villagers.

It therefore was very useful to be able to converse in a protected way. [5]

Many of these argots have been consigned to the history books or are a dying oral tradition.

Perhaps one of the most poignant instances of modern recognition, not only of the language but also the masons as companions, is noted in Spyros Tsoutoumpis’ work ‘A History of the Greek Resistance in the Second World War’, whereby he documents the recruitment of a gang of stonemasons in an ELAS group (Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós) which was the military arm of the National Liberation Front (EAM) during the Greek resistance in the Second World War.

This pattern of recruitment was no less common outside Crete.

The first ELAS group in the area of Grevena, named Astrapi [lightning], consisted of nine men, five of whom hailed from the village of Kidonies with the remainder coming from two adjoining villages.

It is indicative that these men not only shared a common place of origin and family ties but also belonged to a similar occupational and linguistic subculture.

They were all stonemasons, a semi-nomadic social group who shared a cryptic language known as Koudaritika that was spoken in parts of Epirus and western Macedonia.

– Spyros Tsoutoumpis, A History of the Greek Resistance in the Second World War [6]

The Stonemasons’ Guild of St Stephen and St George once again triumph with some other common words and phrases in Mastorika translated into English:

Mob = Members of gang

Kaudas = Master

Kalfas = foreman, second in command

Pelekanoi = stone hewers

Kleidosades = lower masons

Paragioi = apprentice masters

Tsirakia = apprentices

Ntamartzides = Quarrymen

Laspitzis = Plasters (makers of plaster)

Kourasani = pointers (making watertight and concerned the jointing of the bridges)

Tagiadorosa = carpenter/woodcarver

Mastoropoula = labourers or minions

In the next article in our series on the stonemasons, their work, and connections to the Freemasons, we look at the use of identification or masons’ marks – from Egypt to England.

The Stonemasons’ Guild of St. Stephen And St. George

Guild procession in Norwich 2017

Footnotes

Resources

[1] Wikipedia under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 3.0

[2] Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archduke_Joseph_Karl_of_Austria. Cited in John Perkins and Cushing Winship, Historical Brighton, Vol. 2, pp. 46-7 (1902).

[3] A. T. Sinclair – The Secret Language of Masons and Tinkers. The Journal of American Folklore, Oct. – Dec. 1909, Vol. 22, No. 86 (Oct. – Dec. 1909), pp. 353-364.

[4] Ballesteros Curiel, Julio. Verbo dos Arginas: jerga-latin de los canteros. Spain, n.p, 1930.

[5] Ronald Walkey, in ‘A Lesson in Continuity: The Legacy of the Builders’ Guild in Northern Greece’ p. 140 in Dwelling, seeing, and designing: Toward a phenomenological ecology. David Seamon, Ed. State Univ of New York Pr. 1993.

[6] Spyros Tsoutoumpis, ‘A History of the Greek Resistance in the Second World War: The People’s Armies’, Manchester University Press, 2016.

J. Desormaux, “Mélanges savoisiens, VIII. L’argot des ramoneurs”, (1912) 26 Revue de philologie française et de littérature p 77 (ISSN 1245-5733), Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Littérature et art, 8-X-4072, 2011 accessed 7 January 2013.

“Le mourmé, parlé à Samoëns, comme le mènedigne ou mannedigne, en usage à Morzine et à Montriond, est l’argot propre aus frahans, tailleurs de pierre et maçons de ces localités du Chablais.” (mourmé, spoken at Samoëns, as with mènedigne or mannedigne, in use at Morzine and at Montriond, is the argot of the frahans, stonecutters and masons of these places in Chablais district.)

Further Reading

‘The Verb Two Arginas’, Manuel Pintado

https://cvc.cervantes.es/el_rinconete/anteriores/mayo_98/25051998_02.htm

‘Latin two stonemasons’

https://supraterram.wordpress.com/tag/verbo-dos-arginas/

Article by: Philippa Lee. Editor

Philippa Lee (writes as Philippa Faulks) is the author of eight books, an editor and researcher.

Philippa was initiated into the Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons (HFAF) in 2014.

Her specialism is ancient Egypt, Freemasonry, comparative religions and social history. She has several books in progress on the subject of ancient and modern Egypt. Selection of Books Online at Amazon

The Art of the Stonemason

By: Ian Cramb (Author)

Author Ian Cramb was a fifth-generation stonemason who relied on traditional methods to create and restore beautiful stone structures.

In this do-it-yourself manual for homeowners, masonry contractors, and restoration specialists, Cramb drew on his fifty years of life experience in the craft to cover restoration techniques for historic structures in the U.S. and Britain.

The book covers various types of stone, stone-cutting, and traditional mortar mixes for walls, foundations, and buildings.

American Gypsies

By: T. Sinclair

As a rule Gypsies are unwilling to teach a stranger their language. It’ was therefore only by liberal presents of cigars and tobacco to the men and bright silk handkerchiefs to the women and girls that I induced this band to teach me.

Again, Gypsies seldom can read or write, and it is not easy to learn a language accurately from ignorant people. For instance, I asked how they said in Gypsy Will you have a cigar? They said Will tuti lella tav. Later, however, I discovered this phrase meant Will you have a smoke, not Will you have a cigar.

Ignorant people also soon tire when teaching you, and mislead by their answers, saying yes often when they should say no, simply because that happens to make it easier for them.

Frequently their replies are very amusing, and it is difficult to get an answer to your question.

Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece

By: Patrick Leigh Fermor

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Mani compellingly revealed a hidden world of Southern Greece and its past. Its northern counterpart takes the reader among Sarakatsan shepherds, the monasteries of Meteora and the villages of Krakora, among itinerant pedlars and beggars, and even tracks down at Missolonghi a pair of Byron’s slippers.

Roumeli is not on modern maps: it is the ancient name for the lands from the Bosphorus to the Adriatic and from Macedonia to the Gulf of Corinth.

But it is the perfect, evocative name for the Greece that Fermor captures in writing that carries throughout his trademark vividness of description.

But what is more, the pictures of people, traditions and landscapes that he creates on the page are imbued with an intimate understanding of Greece and its history.

Recent Articles: symbolism

Legends and Symbols in Masonic Instruction Explore the significance of Masonic legends and symbols in this insightful post. Discover how Freemasonry imparts wisdom through allegorical narratives and emblematic imagery, revealing profound moral and philosophical lessons. Unveil the deep connections between Masonic teachings and the broader quest for understanding life’s fundamental questions. |

Discover the mystical significance of the number 33. From its mathematical marvels and artistic influence in numerology to its esteemed place in Freemasonry, delve into the history and power of this master number. Explore why 33 holds such profound meaning in various spiritual and philosophical traditions. |

The Practice of Freemasonry - P1 Embark on a transformative journey with Freemasonry, where the exploration of your Center unlocks the Perfect Ashlar within. Through the practices of Brotherly Love, Relief, Truth, and Cardinal Virtues, discover a path of enlightenment and self-improvement. Embrace the universal creed that binds us in the pursuit of our true essence. |

Discover the fascinating history and significance of the Warrant of Constitution within Freemasonry. Unveil the evolution of this crucial authorization, its role in legitimizing Lodges, and its lasting impact on the global brotherhood of Freemasons. Explore the intricate link it provides between tradition and modern practice. |

Freemasonry: Unravelling the Complexity of an Influential Organization Mysterious and captivating, Freemasonry has piqued the interest of seekers and skeptics alike. With its intricate blend of politics, esotericism, science, and religion, this enigmatic organization has left an indelible mark on society. Prepare to delve into the secrets of Freemasonry and unlock its hidden depths. |

Unlocking the Mysteries of Freemasonry: In the hallowed halls of Freemasonry, a powerful symbol lies at the heart of ancient rituals and teachings—the Volume of the Sacred Law. This sacred book not only guides the spiritual and moral journey of Freemasons but also serves as a beacon of universal wisdom and enlightenment. |

The Ancient Liberal Arts in Freemasonry Embark on a journey of self-improvement and wisdom with Freemasonry's guiding principles. Ascend the winding stairs of moral cultivation, analytical reasoning, and philosophical understanding. Embrace arithmetic's mystical properties and geometry's universal truths. Let the harmony of the universe inspire unity and growth. Discover the profound, hidden knowledge in Freemasonry's path to enlightenment. |

Initiation rituals around the world are filled with fascinating elements and different images. One of them is that of darkness. When societies speak of darkness, they often mean a lack of knowledge, a lack of choice, or a symbol of evil. During initiation rituals, darkness is used to represent the initiate's lack of knowledge about the world, society, and initiation in general. It can also represent the initiate's inability to make a choice or endure a situation. Whether you have participated in an initiation rite or not, the meaning of darkness remains an intriguing concept worth exploring. Initiation rituals around the world are filled with fascinating elements and different images. One of them is that of darkness. When societies speak of darkness, they often mean a lack of knowledge, a lack of choice, or a symbol of evil. During initiation rituals, darkness is used to represent the initiate's lack of knowledge about the world, society, and initiation in general. It can also represent the initiate's inability to make a choice or endure a situation. Whether you have participated in an initiation rite or not, the meaning of darkness remains an intriguing concept worth exploring. |

Masonic Deacon rods potentially trace their origins to Greek antiquity, symbolically linked to Hermes' caduceus. As Hermes bridged gods and mortals with messages, so do Masonic Deacons within the lodge, reinforcing their roles through ancient emblems. This connection underscores a profound narrative, weaving the fabric of Masonic rites with the threads of mythological heritage, suggesting the rods are not mere tools but bearers of deeper, sacred meanings that resonate with the guardianship and communicative essence of their divine counterpart, Hermes, reflecting a timeless lineage from myth to Masonic tradition. |

The biblical pillars erected by Solomon at the Temple's porch, hold a profound place in history. These brass behemoths are not mere decorations; they are symbols of strength, establishment, and divine guidance. Explore their fascinating construction, dimensions, and the deep meanings they carry in both biblical and Masonic contexts. |

Unlocking the Mind's Potential: Dive deep into ground breaking research revealing how simple daily habits can supercharge cognitive abilities. Discover the untapped power within and redefine your limits. Join us on this enlightening journey and transform your world! |

Dive deep into the symbolic importance of the trowel in Masonry, representing unity and brotherly love. From its historical roots in operative masonry to its significance in speculative masonry, this article explores the trowel's multifaceted role. Discover its connection to the sword, the story of Nehemiah, and the Society of the Trowel in Renaissance Florence. Unravel the layers of meaning behind this enduring Masonic symbol. |

Symbolism of The Builder's Jewel Batty Langley's "The Builder’s Jewel" (1741) is a visual masterpiece of Masonic symbolism, showcasing Langley's deep understanding of Freemasonry. The frontispiece highlights key symbols like the three pillars and the legend of Hiram Abiff, emphasizing Langley's dedication to Masonic traditions and teachings. |

Unveil the mystique of the colour blue in Masonic symbolism. A hue evoking universal friendship and benevolence, its roots span ancient cultures, infusing Freemasonry's core values. This article explores blue's profound significance, guiding Freemasons towards wisdom and spiritual enlightenment. Discover the fascinating journey of this universal symbol. |

Discover the intriguing world of the plumb in Masonic symbolism with our in-depth analysis. Uncover its rich history, moral teachings, and significance in Freemasonry, guiding members on their path to truth, integrity, and justice. Immerse yourself in the captivating power of this symbol that shapes lives within the brotherhood. |

Unlock the mysteries of Freemasonry with 'The Key,' a profound Masonic symbol. This seemingly simple instrument holds a deeper meaning, teaching virtues of silence and integrity. Explore its ancient roots, from Sophocles to the mysteries of Isis, and discover how it symbolizes the opening of the heart for judgment. |

Unlock the secrets of the Freemasonry with The Blazing Star - a symbol that holds immense significance in their rituals and practices. Delve into its history, meaning and role in the different degrees of Freemasonry with expert insights from the Encyclopedia of Freemasonry by Albert Mackey. Discover the mystique of The Blazing Star today! |

There is no symbol more significant in its meaning, more versatile in its application, or more pervasive throughout the entire Freemasonry system than the triangle. Therefore, an examination of it cannot fail to be interesting to a Masonic student. Extract from Encyclopedia of Freemasonry by Albert Mackey |

The Hiramic Legend and the Myth of Osiris Hiram Abiff, the chief architect of Solomon’s Temple, is a figure of great importance to Craft Freemasonry, as its legend serves as the foundation of the Third Degree or that of a Master Mason. He is the central figure of an allegory that has the role of teaching the Initiate valuable alchemical lessons. Although his legend is anchored in biblical times, it may have much older roots. |

This rite of investiture, or the placing upon the aspirant some garment, as an indication of his appropriate preparation for the ceremonies in which he was about to engage, prevailed in all the ancient initiations. Extract from The Symbolism of Freemasonry by Albert G. Mackey |

The All-Seeing Eye of God, also known as the Eye of Providence, is a representation of the divine providence in which the eye of God watches over humanity. It frequently portrays an eye that is enclosed in a triangle and surrounded by rays of light or splendour. |

What's in a Word, Sign or Token? Why do Freemasons use passwords, signs, and tokens? As Freemasons we know and understand the passwords, signs and tokens (including grips), which are all used a mode of recognition between members of the fraternity. |

A Temple of Living Stones: Examining the Concept of a Chain of Union What are the origins of the Chain of Union? And how did they come about ? The answers may surprise some members as W Brother Andrew Hammer investigates, author of Observing the Craft: The Pursuit of Excellence in Masonic Labour and Observance. |

One of the best loved stories for the festive season is ‘A Christmas Carol’. A traditional ghost story for retelling around the fire on a cold Christmas Eve, it is a timeless classic beloved by those from all walks of life. Philippa explores the masonic allegory connections… |

The Trowel - Working Tool of the Master Mason The Trowel is the symbol of that which has power to bind men together – the cement is brotherhood and fellowship. |

Two Perpendicular Parallel Lines The point within a circle embordered by two perpendicular parallel lines, with the Holy Bible resting on the circle, is one of the most recognizable symbols in Freemasonry. It is also one which always raises a question. How can two lines be both perpendicular and parallel? |

"The first great duty, not only of every lodge, but of every Mason, is to see that the landmarks of the Order shall never be impaired." — Albert Mackey (1856) |

It is common knowledge that the ancient wages of a Fellowcraft Mason consisted of corn, wine, and oil. |

“Do not come any closer,” God said. “Take off your sandals, for the place where you are standing is holy ground.” Exodus 3:5 |

The Secret Language of the Stone Masons We know of Masons' Marks but lesser known are the 'argots' used by the artisans - in part 2 of a series on the social history of the Operative Masons we learn how the use of secret languages added to the mystery of the Guilds. |

The phrase appears in the Regius Poem. It is customary in contemporary English to end prayers with a hearty “Amen,” a word meaning “So be it.” It is a Latin word derived from the Hebrew word - Short Talk Bulletin - Vol. V June, 1927, No.6 |

Egypt's 'Place of Truth' - The First Operative Stone Masons' Guild? Was ancient Egypt's 'village of the artisans' the first operative stone masons' guild? And was their use of 'identity marks' a forerunner of the Mason's Marks of the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages? Read on for some possible answers… |

The Pieces of Architecture and the Origin of Masonic Study Discover the journey of the Apprentice – from Operative to Speculative. This journey has been carried out since the times of operative Freemasonry but today the initiate works in the construction of his inner temple. |

The Builders' Rites - laying the foundations operatively and speculatively The cornerstone (also ‘foundation’ or ‘setting’ stone) is the first stone to be set in the construction of the foundations of a building; every other stone is set in reference to this. |

Applying the working tools to achieve our peculiar system of morality. |

We take an in-depth look at the 47th Proposition of the 1st Book of Euclid as part of the jewel of the Past Master. |

The Cable Tow: Its Origins, Symbolism, & Significance for Freemasons - Unbinding the significance of the cable tow. |

We examine at one of the most impressive moments of the initiatory ceremony, a certain rite known as Circumambulation, and ask what is its meaning and purpose ? |

So, what is the Level? And why do we use it in Freemasonry? |

What is the mysterious pigpen or Masonic cipher that has been used for centuries to hide secrets and rituals? |

The Story of the Royal Arch - The Mark Degree Extracted from William Harvey's 'The Story of the Royal Arch' - Part 1 describes the Mark Degree, including the Working Tools. |

Ashlars - Rough, Smooth - Story of a Stone How we can apply the rough and smooth Ashlars with-in a masonic context |

A detailed look at the Chamber of Reflection: A Revitalized and Misunderstood Masonic Practice. |

Exploring the origin and symbolism of Faith, Hope and Charity |

The Noachite Legend and the Craft What is it to be a true Noachidae, and what is the Noachite Legend and the Craft ? |

In Masonic rituals, Jacob’s ladder is understood as a stairway, a passage from this world to the Heavens. |

What is the meaning of the Acacia and where did it originate ? |

What is the connection with the Feasts of St John and Freemasonry |

The Forget-Me-Not and the Poppy - two symbols to remind us to 'never forget' those who died during the two World Wars. |

Biblical history surrounding the two pillars that stood at the entrance to King Solomon's Temple |

Is there a direct link between Judaism and Freemasonry? |

The symbolism of the beehive in Masonry and its association with omphalos stones and the sacred feminine. |

The Wages of an Entered Apprentice |

An explanation of the North East corner charge which explores beyond one meaning Charity - |

A brief look at the origins of the two headed eagle, probably the most ornamental and most ostentatious feature of the Supreme Council 33rd Degree Ancient and Accepted (Scottish ) Rite |

A Muslim is reminded of his universal duties just as a Freemason. A Masonic Interpretation of the Quran's First Two Chapters |

The three Latin words -{Listen, Observe, Be Silent}. A good moto for the wise freemason |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device