Robert Burns and James Hogg

An Oration delivered to the Annual Burns and Hogg Festival, at Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, Edinburgh, on 24 January 2018.

By: Bro. Kenneth C. Jack, FSAScot FPS, Past Master, Lodge St. Andrew, No. 814, Pitlochry.

Right Worshipful Master, Distinguished guests, Reigning and Past Masters, Worshipful Wardens, brethren all.

First of all, can I thank you Right Worshipful Master, your office-bearers and brethren, for the huge honour you have conferred on me this evening, by asking me to be your main speaker, at this your annual Burns and Hogg Festival.

It is a great pleasure and privilege to be here, and I hope that I can do justice to your choice.

I also wish to thank Bro. Stewart Donaldson, as I know that he had a hand in selecting the speaker for tonight.

Stewart and I have known each other for a few years, having been made acquainted primarily through our mutual interest in Masonic research and history, and I am a keen subscriber, and occasional contributor to his excellent Masonic e-zine which he distributes monthly throughout the Masonic season.

A few years ago, I invited Stewart to deliver the Immortal Memory at my Mother Royal Arch Chapter’s Burns Supper, so I guess Stewart is either returning the compliment or gaining his revenge!

When one is asked to present a talk at the home of one of the oldest Lodges in the world, there can really only be one answer, and of course when asked I quickly accepted.

After doing so, I then doubted the wisdom of my decision. Although I know a bit about Burns and Hogg, I am not an acknowledged expert by any means; neither am I a noted or talented orator.

However, my wife quickly reassured me by advising: “Kenny, don’t worry about being witty and clever – just be yourself.” So, brethren, for better or worse, I will take that advice, and hope that it will carry me through this evening.

Brethren, as I say, I do not profess to be an expert on either Burns or Hogg, and I do not consider what follows as a lecture. Far be it for me to lecture the brethren of this ancient Lodge on two of your greatest members and Poets Laureate.

My purpose this evening, I think, is to simply help in commemorating the immortal memory of both these great men and Masons, and if I can tell you anything about them that you do not know, then so much the better.

I will talk about the lives and work of both men, before moving on to their respective Masonic careers, and will finish off by describing the similarities and differences between the two men. Along the way, I will of course hopefully regale you with brief samples of their work.

ROBERT BURNS

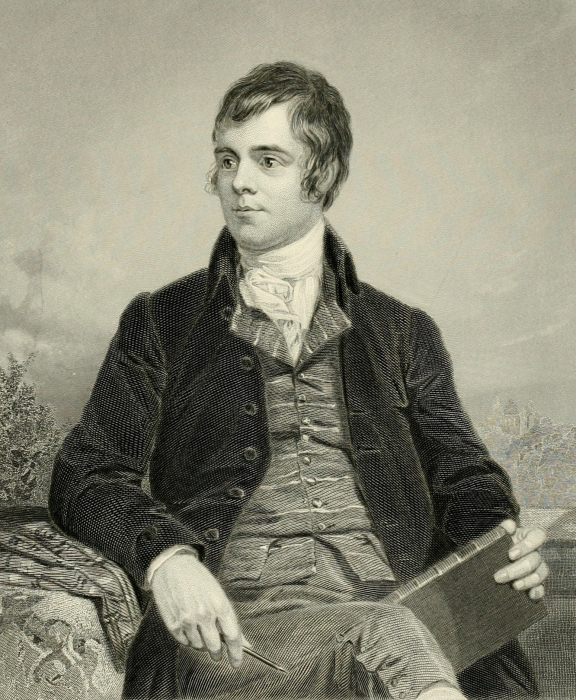

Robert Burns. Engraved version of the Alexander Nasmyth 1787 portrait.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Robert Burns was born on 25 January, 1759 at Alloway, Ayrshire, to William Burnes and Agnes Broun, the oldest of seven children, the others being Gilbert, Agnes, Annabella, William, John, and Isabella.

William Burnes was originally from Kincardineshire, and went by the surname Burness, which was later shortened to Burns.

The Burness family had for several generations been employed as farmers in that area, and father William was particularly skilled in that occupation.

The Burns’ Cottage, Alloway, Ayrshire. By DeFacto – Own work.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Due to a downturn in his fortunes William was compelled to move south to Ayrshire, via Edinburgh, where he pursued his occupation as gardener with various employers, before being taken on as a gardener/overseer with a Mr. Ferguson of Doonholm.

Here he built himself a small clay cottage with his own hands. It was whilst living and working there that he met and married Agnes Broune, the daughter of a Carrick farmer.

In 1766, when the poet was seven years old, the family moved to Mount Oliphant, a 70-acre farm, a few miles above the mouth of the River Doon.

They stayed there for ten years, before moving on to a larger farm, Lochlie, a little further north in the parish of Tarbolton.

Burns senior continued in this farm for another seven years, but a mix of poor seasons, and disputes with the landlord’s factor, all had an adverse effect on his health, and on 13 February 1784, the poet’s father passed away.

The dispute with the factor was no doubt in Burns’ mind, when he penned the lines in his poem the “Twa Dogs”:

Poor tenant bodies, scant o’ cash,

How they maun thole a factor’s snash….

In his youth, Burns’ father served him well by employing a John Murdoch as a tutor, who encouraged the young Burns to study various subjects, which Burns himself accredited as providing him with the knowledge which later assisted him in writing his poetry.

His brother Gilbert had this to say about Murdoch:

With Murdoch, we learned to read English tolerably well, and to write a little. He taught us, too, the English Grammar. I was too young to profit much by his lessons in grammar, but Robert made some proficiency in it, a circumstance of considerable weight in the unfolding of his genius and character.

It has to be said, that for poor working-class boys the reading that Robert and Gilbert did under the tutelage of Murdoch was impressive, including the likes of Shakespeare, Locke’s “Essay on the Human Understanding”, Stackhouse’s “History of the Bible”, Taylor’s “Scripture Doctrine of Original Sin”, and other suchlike works.

It is hardly surprising that Burns was considered by some to be somewhat of a polymath.

It was probably during this period that Burns developed an interest in poetry, and by 1782, his interest in poetic composition was developing. A month after his father’s death, Burns moved with the family to Mossgiel Farm, about three miles from Lochlie, within the Parish of Mauchline.

Burns continued to farm, and one fateful November day in 1785, the “ploughman poet” was engaged with his plough on the farm, when he turned up the nest of a mouse. This left him with such feelings of remorse as caused him to pen one of his most famous verses: “To a Mouse”.

Wee sleekit, cowerin’ tim’rous beastie,

O’ what a panic’s in thy breastie,

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi bickering brattle,

I wad be laith to rin and chase thee,

Wi murderin’ pattle.”I’m truly sorry man’s dominion

Has broken nature’s social union,

That justifies that ill-opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An fellow mortal.

The second last verse of the poem contains the lines:

But Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o mice and men,

Gang aft agley,

An lea’e us nought but grief and pain,

For promis’d joy!

The famous American writer John Steinbeck, himself a Freemason, was a fan of Robert Burns, and owned books of his poetry. Steinbeck borrowed a line from this verse of the poem for his famous short novel “Of Mice and Men” which like Burns’ poem, deals with themes of thwarted endeavours and aspirations.

It was also in 1785 that Burns met Jean Armour, and in the September of that year he “attested” his marriage to her. Much has been said over the years concerning the “womanising” of Robert Burns, and I do not intend entering that particular debate here tonight, but it is sufficient to say that he had a fondness for “the lassies,” although Burns scholar Dr Catherine Smith contends that issue is rather overblown, and that because of his insufficient means, Burns often simply accepted any blame thrown at him in that connection, rather than go to the expense and trouble of fighting any claims of fatherhood.

On 1 September 1786, Burns first considered emigrating to Jamaica, to take up a post as a book-keeper on a plantation, a controversial move which has been pored over by historians over the years.

However, Burns’ literary career really started to take off around this period, and he began to receive backing from many influential people, particularly in Edinburgh; and by September of that year, he abandoned all notions of emigrating to the Caribbean and began considering a career as an excise man.

Having built up a considerable store of work; on 3 April 1786, proposals for the so-called Kilmarnock edition of poems were sent to the printers, and were published eleven days later, and Burns became a published author. In order to achieve this, his Masonic connections were key.

THE FREEMASONS’ POET LAUREATE

The Inauguration of Robert Burns as Poet Laureate of the Lodge 1846, William Stewart Watson

IMAGE LINKED: Via Lodge St Andrew http://www.standrew518.co.uk/BURNS/Poet_Laureate.php

Burns’ life and career is inextricably linked to Freemasonry.

His Masonic career commenced on 4 July 1781, when aged 23 years, he was initiated into St. David’s Lodge, No. 174, Tarbolton.

He was introduced to the fraternity by John Rankine of Adamhill, near Tarbolton, and he afterwards dedicated a number of poems to Rankine, including: ‘Epistle wrote to John Rankine’, and ‘Lines to John Rankine’.

Rankine appears to have been Burns’ proposer, and he was initiated by the Master of the Lodge, Alexander Wood, a local tailor.

In mid-July, Burns was spending a lot of time in Irvine, learning the trade of flax-dressing, and because of this, and as the Lodge Minutes record, “Robert Burns in Lochly” was Passed and Raised on 1 October that year.

Rankine apparently learned early on that an Elizabeth Paton was pregnant by Burns, and mercilessly ribbed him about it. By way of revenge, Burns in his “Epistle to John Rankine” wrote:

O rough, rude, ready-witted Rankine,

The wale o cocks for fun and drinkin!

There’s mony godly folks are thinkin’

Your dreams and tricks

Will send you, Korah-like, a sinkin’

Straught to auld nicks.

One could be forgiven for thinking that John Rankine was one of the Masons referred to in Burns’ “Second Epistle to Davie”, (David Sillar) when he writes:

For me, I’m on Parnassus’ brink,

Rivin’ the words to gar them clink:

Whyles daez’t wi love, whyles daez’t wi drink,

Wi jauds or Masons:

Ah whyles, but ay owre late. I think

Braw sober lessons.

The famous 19th century Scottish writer and no mean poet himself Professor John Stuart Blackie wrote:

It will be observed in his second letter to Davie there is special mention made of “masons,” and there can be little doubt that not a few of the Masons in those days were not much better than the “jauds” with whom they are coupled.

Of course, there is a good side in Freemasonry; so far indeed as it means humanity and good fellowship and brotherly recognition, and kindly help in need, there cannot be a better thing: but in the latter part of the last century, in such a village as Tarbolton or Mauchline, it practically meant only a convivial meeting of jolly good fellows, which might often be without wit, but never could be without drink.

Into the mystical brotherhood at Tarbolton, the poet had flung himself with all the ardour of the social enjoyment, which, next to love, supplied the most potent steam of his soul.

I have been unable to confirm it, but there is some reason to believe that Professor Blackie was a Freemason himself, as he wrote a very positive poem regarding Freemasonry, extolling the universal and non-sectarian nature of the Craft.

If so, he clearly considered himself a more sober and sensible Mason than the Masons of Burns’ time. Blackie’s half-brother George Stodart Blackie was most certainly a very well respected and high-ranking Freemason of his day.

For Burns himself though, Freemasonry was a mixture of mysticism and conviviality. In his work, the symbolism and allegory of Craft ritual was certainly not lost on him, but the social side of fraternity was at least as equally important to him, and this found its way into his verses too of course.

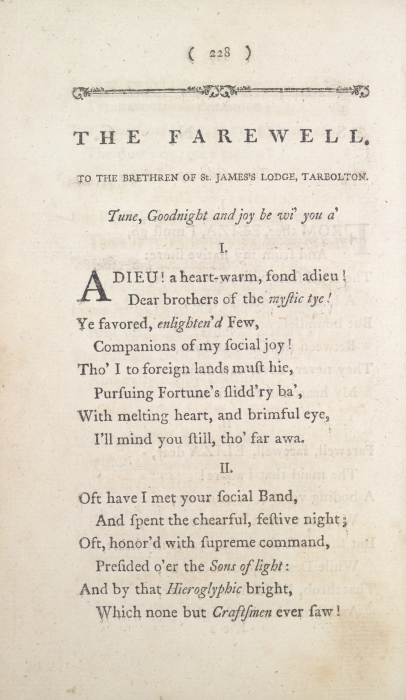

An example of this is to be found in his poem: “The Farewell to the Brethren of St. James Lodge, Tarbolton”, written it is believed for a meeting of the Lodge on 24 June 1786, at a time when Burn’s was still set to emigrate to Jamaica.

ADIEU! A heart-warm, fond adieu!

Dear brothers of the Mystic Tye!

Ye favour’d, enlighten’d Few,

Companions of my social joy!

Tho’ I to foreign lands must hie,

Pursuing fortune’s slidd’ry ba’

With melting heart, and brimful eye,

I’ll mind you still, tho’ far awa.

Oft have I met your social Band,

And spent the cheerful, festive night;

Oft honor’d with supreme command,

Presided o’er the Sons of light

And by that Hieroglyphic bright,

Which none but Craftsmen ever saw!

Strong Mem’ry on my heart shall write

Those happy scenes when far awa!

May Freedom, Harmony and Love

Unite you in the grand Design,

Beneath th’ Omniscient Eye above,

The glorious ARCHITECT Divine!

That you may keep the’ unerring line,

Still rising by the plummet’s law

Till Order bright completely shine,

Shall be my Prayer when far awa”.

And You, farewell! Whose merits claim,

Justly that highest badge to wear!

Heav’n bless your honour’d noble Name,

To MASONRY and SCOTIA dear!

A last request permit me here,

When yearly ye assemble a’,

One round I ask it with a tear,

To him, the Bard that’s far awa.

Burns rose through the offices in the Lodge and became Depute-Master on 27 July 1784.

In those days when landed gentry or members of the aristocracy held the honorary position of Master, the Depute-Master was effectively in charge of running the Lodge, and Burns appears to have fulfilled the office satisfactorily and was re-elected to the post in July 1786.

As his literary renown grew, Burns began to gain the acquaintance of certain members of the aristocracy, which appears to have been facilitated through his Masonic activities.

These acquaintances included the likes of Lord Torpichen, Lord Pitsligo, Lord Elcho, the Earl of Eglinton, and the Earl of Glencairn, and Burns acquired the latter’s patronage.

It also put him in contact with influential people such as Gavin Hamilton, and James Dalrymple.

Realising they had a potential star on their hands, Lodges began to assist Burns in getting his work into print, by encouraging subscribers to contribute towards the cost of printing and publishing books of his work, a sort of crowdfunding of its day.

Gavin Hamilton, a brother Mason, helped persuade the brethren of St James Lodge to club together, and this resulted in the publication of Burns’ first book: “Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect”.

The book was priced at three shillings. (1786). Burns dedicated the book to Hamilton, his “friend and brother,” further adding: “the poor man’s friend in need, the gentleman, in word and deed.”

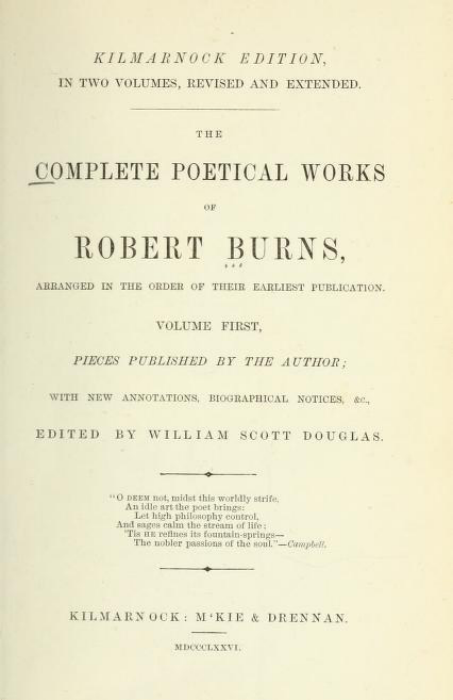

Title page of the “Kilmarnock” edition of Robert Burns’ poems, Kilmarnock: McKie and Drennan (1876)

The book was published in Kilmarnock, where Burns was admitted into St. John’s Lodge, on 26 October 1786.

This was apparently the first time that Burns was acknowledged as a “poet,” as the Lodge Minutes refer to him as such.

The brethren of this Lodge acquired 350 copies of Burns’ book, and the book therefore became known as the “Kilmarnock” edition.

The Master of the Lodge subscribed to 35 copies, and another brother, 75 copies.

Unfortunately, sales from the book were insufficient to provide Burns with financial stability, and another edition had to be forthcoming.

The second edition was also produced under Masonic patronage in 1787, the printer being a fellow Mason, William Smellie; and engraver, another fellow Mason called Alexander Naesmith.

The publisher was William Creech, who Burns also apparently met at a Masonic gathering. This was effectively a reprint of the Kilmarnock edition, but with a hundred more pages, and twenty-two additional poems.

The book became known as the Edinburgh Edition. Apparently Burns earned five hundred pounds from the book, but in the process forfeited copyright to Creech, selling it for one hundred guineas.

Burns Masonic connections were further enhanced when he was admitted into this ancient Lodge in 1787.

On 6 February that year, the Prince of Wales was initiated into Freemasonry in the Star and Garter Lodge in London.

Canongate Kilwinning apparently responded to this by calling a meeting with a view to discussing the question of sending their congratulations.

According to tradition, it was at this same meeting that the Master of the Lodge, Ferguson of Craigdarroch, decided to confer upon Burns the title of “Poet-Laureate of the Lodge”.

Burns had already referred to himself as “Laureate” in a piece he wrote on 3 May 1786 in which he wrote:

To phrase you, an” praise you,

Ye ken your LAUREATE scorns:

The Pray’r still, you share still,

Of grateful Minstrel; Burns.

In January 1787, two months before Burns’ inauguration into this Lodge, the Grand Master Mason of Scotland, while attending a Masonic gathering at which Burns was present, proposed a toast to “Caledonia, and “Caledonia’s Bard, Brother Robert Burns.”

Burns’ reaction to this is recorded in a letter to his friend John Ballantine:

As I had no idea such a thing would happen, I was downright thunderstruck, and trembling in every nerve, made the best return in my power.

Just as I had finished, some of the Grand Officers said so loud as I could hear, with a most comforting accent, “Very well indeed!” which set me something to rights again.

Tradition informs us that Burns was subsequently inaugurated as Poet-Laureate of Canongate Kilwinning Lodge, No. 2, on 1 March 1787, an event commemorated in Brother Stewart Watson’s famous painting.

Historians have argued over this point for many years, but that is hardly our concern this evening.

Twenty years later, another working-class poet was to have the same honour bestowed upon him, a title which as the Lodge Minutes apparently record had been in abeyance since the death of the famous Robert Burns.

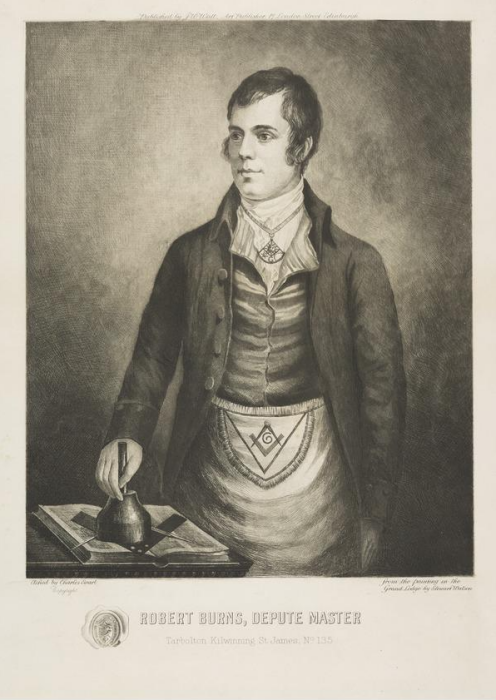

Robert Burns, Depute Master Tarbolton Kilwinning St James No. 135. National Galleries Scotland.

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

I will now put Robert Burns to one side for the time being, and concentrate, on our other subject for the evening: James Hogg, otherwise known as “The Ettrick Shepherd”.

JAMES HOGG

James Hogg, Scottish Poet By Charles Rogers – Project Gutenberg’s The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volumes I-VI., by Various – http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22515/22515-h/vol_ii.html

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

James Hogg was born in 1770 in a small farmhouse at Ettrick Hall, Selkirkshire, in the Scottish Borders, to Robert Hogg, a farmer, and his wife Margaret (nee Laidlaw). He was baptised on 9 December.

The farmhouse was situated in a remote spot, between the hills of a sheep farming district. Hogg would later become a great fan of Robert Burns, and as such claimed that he shared the same birthdate, 25 January, as the great Bard.

However, available evidence suggests he was born in late November of 1770. Hogg’s ancestors had been sheep farmers and tenant farmers in the area for generations, and therefore his background ideally placed him in a position to make the struggles of the working class a recurring theme in his later works.

Hogg’s early life was therefore quite a closed one, consisting as it did of witnessing his parents’ routine daily grind alongside his siblings. Hogg later recalled that he believed the area was “the very centre of the world,” and in his poem ‘Farewell to Ettrick,’ wrote:

I thought the hills were sharp as knives,

An’ the braed lift lay whomel’d on them,

An glowr’d wi” wonder at the wives

That spak o’ ither hills ayon’ them.

Much like Burns, Hogg’s schooling was less than formal on occasions. Hogg and his older brother did attend school, usually in the winter months, but when summer arrived, the boys were expected to do their bit on the farm: herding cows, running errands for the harvesters, and generally assisting the regular farm workers in their duties.

The boys learned to read by using the easier parts of various religious texts contained within the family home.

However, the outdoor life was certainly a healthy one, and Hogg and his siblings did not want for food. He had a good close family life, which provided emotional security, and he had the freedom to wander the countryside exercising his imagination, which would be put to later good use.

He and his brother William clearly enjoyed their wild sojourns in the countryside as Hogg’s later poem: “A Boy’s Song”, clearly shows:

Where the pools are bright and deep,

Where the gray trout lies asleep,

Up the river and o’er the lea,

That’s the way for Billy and Me.”

Where the blackbird sings the latest,

Where the hawthorn blooms the sweetest,

Where the nestlings chirp and flee,

That’s the way for Billy and me.

Where the mowers mow the cleanest

Where the hay lies thick and greenest,

There to trace the homeward bee,

That’s the way for Billy and me.

Where the hazel bank is steepest,

Where the shadow falls the deepest,

Where the clustering nuts fall free,

That’s the way for Billy and me.

Why the boys should drive away,

Little sweet maidens from the lay,

Or love to banter and fight so well,

That’s the thing I never could tell

“But this I know, I love to play,

Through the meadow, among the hay;

Up the water and o’er the lea,

That’s the way for Billy and me.

Hogg’s father dealt in sheep, reared large numbers, and drove them to market in Scotland and England.

However, in around 1776, due to a drop in the market price of sheep, and his principal debtor absconding, he fell into financial ruin, and was declared bankrupt. The family lost their home, and their belongings were sold off at auction.

Hogg was only six years old at the time, and it is believed that this nurtured in him strong sympathies for the poor and dispossessed, which themes would later feature in his work.

However, the family were not homeless for long, as a Walter Bryden of Crosslee rented the farmhouse at Ettrick himself, and employed Robert Hogg as his shepherd.

Due to the family’s strickened circumstances, the children were sent out to work, and at the very tender age of seven years, young Hogg was being employed to herd cows, his wages for doing so being a “ewe lamb, and a new pair of shoes.”

At times Hogg was treated very harshly by his employers and he stated: “From some of my masters, I received very hard usage: in particular, while with one shepherd, I was often nearly exhausted with hunger and fatigue.”

The poetical works of the Ettrick Shepherd, Blackie & Son., Edinburgh, 1838-1840

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Despite his harsh existence, Hogg became interested in music, and at the age of sixteen years, saved up five shillings to buy a violin.

He practiced playing in the cowhouse of the farm, or the stable, where he also had his bed. There he was able to practice all his favourite tunes without disturbing anyone.

He continued in employment as a shepherd for several “masters” over a period of years. Hogg’s love of music is demonstrated in the aptly titled: “The Shepherd Boy’s Song”:

Music has power to still the waves-

To break the cloud, an’ bend the willow-

To wake the dead out o’ their graves,

An’ bang frae ‘neath the stormy billow:

To make the fays o’ glen and grove

Skip wildly o’er their velvet flooring:

But when it pours from lips we love,

Oh! ‘tis sae sweet, ‘tis past enduring.

At eighteen years of age, Hogg was working for Mr. Laidlaw at Willenslee. He was now a man, pursuing his proper occupation as a shepherd. Here he had more leisure time and took to reading more.

It was here that he first read, “The Adventures of William Wallace”, by Blind Harry, and Ramsay’s “The Gentle Shepherd”.

These were both poetical works, and despite his later interest in poetry, he found them difficult to follow and lamented the fact they were not available in prose.

By the age of nineteen years, Hogg is said to have been attractive to women, and said of himself that he possessed an “ardent disposition”.

He was apparently highly-sexed and wrote up a number of the more amorous adventures of his youth, in his story “Love Adventures of Mr. George Cochrane”.

In this story, a young man lies all day in the heather waiting to meet up in the evening with a farmer’s daughter in order to have a dalliance with her, a liaison which he knows would not be approved by her father.

He later leaves the father’s house by way of an upstairs window. In addition to literary considerations, we can see here similarities with his hero Robert Burns.

In 1790 Hogg moved to Blackhouse Farm, where the Master’s son was the poet William Laidlaw, who became his closest friend.

It was here that Hogg’s ability as a writer and poet was nurtured, and his Master James Laidlaw proved to be more of a father figure than an employer.

William Laidlaw is believed to have introduced Hogg to a circulating library run by an Alexander Elder in Peebles, where he might have read the poetry of Pope and Goldsmith, as well as some of the more classic works.

Hogg remained for ten years at Blackhouse during which time he made significant literary progress. It is believed his earliest literary efforts were made in 1793 or 1794, as his first published poem: “The Mistakes of a Night”, appeared in the Scots Magazine in October 1794.

He wrote songs some of which were sung by girls in a local choir, and he gained the local epithet: “Jamie the poeter”. But apart from these less formal songs, he also wrote classier poems based on his reading of the standard eighteenth century works.

During his years at Blackhouse, Hogg built up a portfolio of his work. In the winter months, his flocks of sheep required constant attention, but he carried sheets of paper stitched together while he was on the hillside and noted down words as they entered his head.

In 1800 Hogg returned to Ettrickhouse, where he took over the running of the farm for his father.

It was around this time that Hogg made the acquaintance, of the writer Walter Scott, who was not yet as famous as he would later become, and Hogg contributed some ballads to his Minstrelsly of the Scottish Borders.

Scott published a third volume of this work in May 1803, and Hogg contributed a number of his poems and ballads to it.

Hogg later penned a poem: “Lines to Sir Walter Scott Bart”:

Ah! could I dream when first we met,

When by the scanty ingle set,

Beyond the moors where curlews set,

In Ettrick’s bleakest, loneliest sheil,

Conning old songs of other times,

Most uncouth chants, and crabbed rhymes:

Could I e’er dream that wayward wight,

Of roguish joke, and heart so light,

In whose oft changing eye I gazed,

Not without dread the head was crazed,

Should e’er, by genius force alone, Skim o’er an ocean sailed by none,

All the hid shoals of envy miss,

And gain such noble port as this?

In 1807, a book of Hogg’s poems: “The Mountain Bard”, and his article on the care of sheep: “The Shepherd’s Guide”, were published by printer Archibald Constable.

In the same year, he acquired two Dumfriesshire farms, Corfardin, and Locherben, which failed, and he was declared bankrupt. He had love affairs with two Borders’ girls, which resulted in two daughters being born.

The kirk session took notice of this, what they called uncleanness, and he was called to receive a rebuke. Again, we can see similarities with his hero Robert Burns.

In 1810 Hogg moved to Edinburgh for several years where he started a literary magazine which he entitled The Spy, which he used to test literary themes which would preoccupy him throughout his career, which included attention to matters of a sexual nature which affronted some of his readers.

Perhaps a parallel could be drawn between this and Burns’ collection of verse: “The Merry Muses”, in which was collected a number of verses of a bawdier character.

About seven years later Hogg began contributing his work to the Tory publisher William Blackwood and continued to do so for the remainder of his life.

Blackwood had launched his: Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in October 1817.

On 28 April 1820, Hogg married Margaret Phillips, who came from a wealthy south-west farming family, and she bore him a son and four daughters.

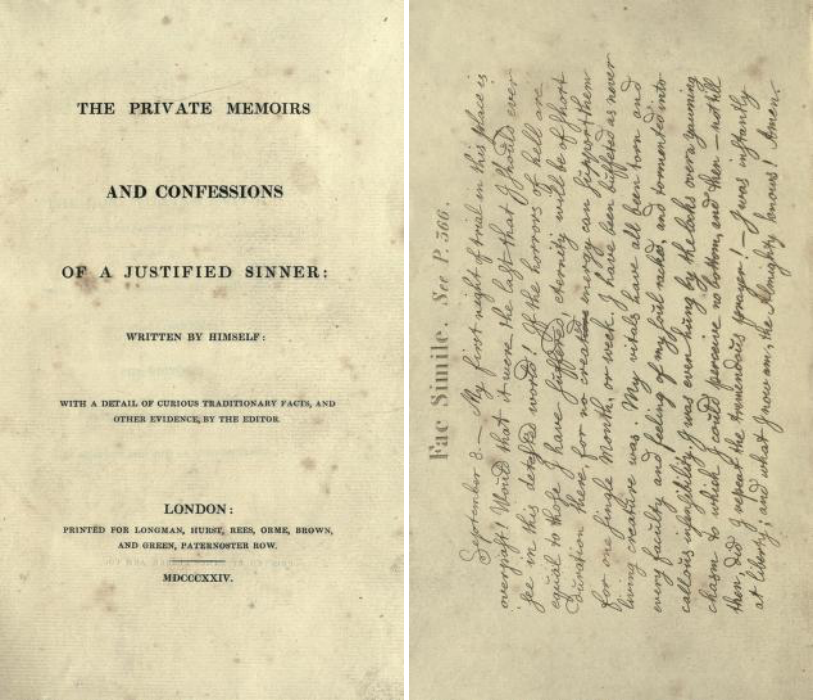

In 1823, he wrote a book, published in 1824, which is now considered to be his most accomplished work of prose: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner.

The novel is set in Edinburgh, and primarily concerns a character by the name of Robert Wringhim, who is the son of a Calvinistic predestinarian Minister, possibly born out of wedlock, whilst Robert’s mother was married to her previous husband.

Robert has been brought up to believe in predestination, a doctrine which suggests that God had pre-ordained a person’s destiny, and that person will be saved regardless of what happens to them or whatever they may do. The chosen few so to speak.

Robert meets an apparent demon by the name of Gil-Martin, but who Robert actually believes to be Peter the Great of Russia.

Gil-Martin encourages Robert in the “holy work” of purifying the world and ridding it of evil. In the course of this he kills his brother and his mother.

The book deals with a number of themes, including religious fanaticism, the battle between good and evil, and mental illness.

One comes away from the novel thinking that Robert must suffer from paranoid schizophrenia or some form of split personality disorder, possibly hereditary, but exacerbated by his strict religious upbringing.

It is believed by some to be one of the first crime novels and is also believed to have influenced Robert Louis Stephenson to write his famous novel: “Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde”.

One of the most profound parts of the novel, not to mention humorous is when the Rev. Wringhim, challenges his Beadle, John Barnet, for apparently spreading rumours about the Rev. being Robert’s true father:

So, then John, you positively think, from a casual likeness, that this boy is my son?

Man’s thoughts are vanity, sir; they come unasked, an’ gang away without a dismissal, an’ he canna help them. I’m neither gaun to say that I think he’s your son, nor that I think he’s no your son: sae ye needna pose me nae mair about it.

Hear then my determination, John: If you do not promise to me, in faith and honour, that you never will say, or insinuate such a thing again in your life, as that that boy is my natural son, I will take the keys of the church from you, and dismiss you my service.

John pulled out the keys, and dashed them on the gravel at the reverend minister’s feet.

There are the keys o’ your kirk, sir! I hae never had muckle mense o’ them sin ye entered the door o’t. I hae carried them this three and thirty year, but they hae aye been like to burn a hole I’ my pouch sin’ ever they were turned for your admittance.

Tak them again, an’ gie them to wha you will, and muckle gude may he get o’ them. Auld John may dee a beggar in a hay barn, or at the back of a dike, but he sall aye be master o’ is ain thoughts, an’ gie them vent or no, as he likes.

As indicated, Hogg continued to write for the remainder of his life and left a huge amount of work behind.

Although both he and Burns achieved minor celebrity in their day, it is nothing compared to the high regard and respect that they have nowadays.

HOGG THE FREEMASON

Throughout his career, Hogg was in contact with a number of Freemasons, including John Wilson, the Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh, who under the pseudonym “Christopher North” created the “Noctes Ambrosianae”, which appeared in Blackwood’s magazine, and consisted of a collection of conversations between different characters, including a semi-fictional “Ettrick Shepherd,” based on Hogg himself.

Hogg occasionally contributed to the series, and it helped his popularity as a poet. Wilson was initiated in Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, in 1830, and served as Depute-Master in 1837/38.

In 1835, Hogg was becoming rather frail, but on 16 January that year Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, decided to ask him if he would become their Poet Laureate, succeeding Robert Burns.

The Lodge decided to ask him to attend their meeting on 6 February 1835, at which point he would be initiated into Freemasonry, and installed as their Poet Laureate.

John Forbes, a lawyer, and personal friend of Hogg was asked to write him with this proposal which he did on 17 January 1835.

This prompted a response from Hogg, dated 25 January:

I am sixty-five years of age this night.

I am not a Mason, and never have been, having uniformly resisted the entreaties of my most influential friends to become one.

I am, however, intensely sensible of the high honour intended me, which coming to my hand on the morning of my birthday, has I feel, added a new charm to the old shepherd’s life.

My kindest respects to the Hon. Master and Members of the Lodge, and say that I cannot join them, nor be initiated into the mysteries of the art, for I know I should infallibly**** And alas! My dear John.

I am long past the age of enjoying Masonic revels. I shall, however, be most proud to become nominally the Poet Laureate of the Lodge, to have my name enrolled as such, and shall endeavour to contribute some poetic trifle annually.

In light of this, on 1 May, 1835, the Lodge further resolved to travel to Hogg to initiate him, and this time Brother Adam Wilson wrote to Hogg inviting him to meet with the Lodge members at Innerleithen and be “father of the feast”, adding that “I will leave you to guess what further honours may be intended for you, as Masons never travel without a purpose.”

A week later, two members of the Lodge went to Hogg’s home to accompany him to a meeting of the Lodge.

They spent the morning fishing, before repairing to St. Ronan’s where a Lodge was formed; Lodge paraphernalia having been brought especially from Edinburgh.

The Lodge was properly constituted, and Hogg was initiated, passed, and raised, and inaugurated Poet Laureate of the Lodge.

The brethren then held a harmony where normal toasts were drunk, including one of course for the newly initiated Bro. James Hogg.

Hogg replied:

The first time it ever entered my head to court the Muses was upon the occasion of my having heard recited “The Cottar’s Saturday Night”.

I learned it by heart, and I thought I would try if I could do something like it.

I have experienced great kindness from my literary friends; indeed, I will do Burns the justice to say that he had to struggle through far greater difficulty than myself, and consequently is entitled to higher praise.

Celebrations continued well into the night, with Hogg regaling the brethren by singing some of his own songs.

Some sceptics have argued that Hogg’s late interest in Freemasonry was prompted by a belief that joining Burns as a Poet Laureate of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, would do sales of his own work no harm at all.

Certainly, he had little or no engagement with Freemasonry in the few months more he had to live, and unlike Robert Burns, he does not appear to have been as committed to it.

BURNS & HOGG COMPARISONS

When one comes to making comparisons between Burns and Hogg, one has to accept the fact that Hogg was the more prodigious writer. This may simply be because Burns lived a much shorter life than Hogg.

Burns died on 21 July 1796, at the tender age of 37 years. Hogg died on 21 November 1835, at the comparatively ripe old age of 65 years. What Burns may have achieved had he lived longer we can only guess at.

Burns’ work was largely confined to poems and songs, but Hogg was active in a whole range of other genres: a periodical; novels; short stories: songs: literary essays; a travel narrative; dramatic tales; and a memoir.

This effectively meant that Hogg not only carried on Burns’ tradition, but expanded it for future working-class writers, who no longer felt restricted to so-called working-class themes, but could in fact write what they wanted to.

Both Burns and Hogg were from poor working-class backgrounds and grew up in harsh rural environments where working conditions were extremely difficult.

Both had a limited education; Burns having the advantage of being educated at times by tutors, Hogg being largely self-taught.

Both were also raised on the fairy tales, myths, and legends of their respective communities, which would have a distinct impact on their later prose and poetry.

Both were voracious readers at an early age, and devoured a wide variety of literature, which included poetry and the more classical works of literature.

They also drew out the Scottish tradition of poetry and song, and they contributed a large number of songs, in the process helping to keep that tradition alive.

In order to get their work noticed, both had to move to Edinburgh, where they enjoyed the patronage of prominent, wealthy, and influential men; many of whom were Freemasons.

As indicated earlier, both were harsh critics of religious fanaticism, and hypocrisy; particularly of the Kirk, Burns most notably in “Holy Willie’s Prayer”, and Hogg in his “Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner”.

At various points in their lives, both embarked on tours of Scotland; and carrying with them ink and paper, wrote down their thought on the sights and characters which they came across during their travels.

And of course, we cannot overlook their fondness for the lasses, which resulted in them falling foul of the kirk authorities and the lasses’ fathers.

Neither man was very capable with money, which they had in any amount only sporadically.

Neither of them became rich, and they only achieved minor celebrity in their own time.

However, in later years, both men acquired a greater appreciation, and fame, and their works became recognised for their genius.

And so, we are here this evening brethren, to celebrate the lives and works of both these great men, whose names and legend will endure for all eternity.

As William Harvey said of Burns: “In his best and most serious writings, in the highest flights of his genius, the spirit of Masonry, is ever present, leading, directing, dictating, inspiring.”

In his biography of Hogg, the Reverend Thomas Thomson wrote something which might well be applied to both great men. Of the Shepherd, he wrote:

Here the learned and the talented in their pilgrimage, will be reminded of the untaught one whose genius made him all that they seek to be.

Here the poet will muse until his emulation is kindled with somewhat of the undying flame of him who has passed away.

Here even the rustic, while he journeys near the spot, or rests amidst his labours: will ask himself the question, “May not I do something to benefit the world, and be remembered when I am no more?”

And with all, the question will arise, which was asked by so many even while he was still living, when will the world see such a shepherd again?

Brethren, please charge your glasses and be upstanding, and help me toast the immortal memory of your Poets Laureate: Brothers Robert Burns and James Hogg.

Article by: Kenneth C. Jack

Kenneth C. Jack FPS is an enthusiastic Masonic researcher/writer from Highland Perthshire in Scotland.

He is Past Master of a Craft Lodge, Past First Principal of a Royal Arch Chapter, Past Most-Wise Sovereign of a Sovereign Chapter of Princes Rose Croix.

He has been extensively published in various Masonic periodicals throughout the world including: The Ashlar, The Square, The Scottish Rite Journal, Masonic Magazine, Philalethes Journal, and the annual transactions of various Masonic bodies.

Kenneth is a Fellow of the Philalethes Society, a highly prestigious Masonic research body based in the USA.

Recent Articles: Kenneth C. Jack

Observations on the History of Masonic Research Archaeology is often associated with uncovering ancient tombs and fossilized remains, but it goes beyond that. In a Masonic context, archaeology can be used to study and analyze the material culture of Freemasonry, providing insight into its history and development. This article will explore the emergence and evolution of Masonic research, shedding light on the challenges faced by this ancient society in the modern world. |

Anthony O'Neal Haye – Freemason, Poet, Author and Magus Discover the untold story of Anthony O’Neal Haye, a revered Scottish Freemason and Poet Laureate of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2 in Edinburgh. Beyond his Masonic achievements, Haye was a prolific author, delving deep into the history of the Knights Templar and leaving an indelible mark on Scottish Freemasonry. Dive into the life of a man who, despite his humble beginnings, rose to prominence in both Masonic and literary circles, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire. |

Rosicrucianism and the Gowrie House Mystery Unearth the mystifying intersections of Rosicrucianism and the infamous Gowrie House Mystery. Dive into speculative claims of sacred knowledge, royal theft, and a Masonic conspiracy, harking back to a fateful day in 1600. As we delve into this enthralling enigma, we challenge everything you thought you knew about this historical thriller. A paper by Kenneth Jack |

Thomas Telford's Masonic Bridge of Dunkeld Of course, there is no such thing as a ‘Masonic Bridge’; but if any bridge is deserving of such an epithet, then the Bridge of Dunkeld is surely it. Designed by Scotsman Thomas Telford, one of the most famous Freemasons in history. |

The masonic and orange orders: fraternal twins or public misperception? “Who’s the Mason in the black?” |

Kenneth Jack's research reveals James Murray, 2nd Duke of Atholl – the 'lost Grand Master' |

An Oration delivered to the Annual Burns and Hogg Festival, at Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, No. 2, Edinburgh, on 24 January 2018. By Bro. Kenneth C. Jack, FSAScot FPS, Past Master, Lodge St. Andrew, No. 814, Pitlochry. |

William Winwood Reade was a Scottish philosopher, historian, anthropologist, and explorer born in Crieff, Perthshire, Scotland. The following article by Kenneth Jack, provides some hints that William may have been a Freemason, but there is presently no definitive evidence he was. |

What's in a name? A brief history of the first Scottish Lodge in Australia - By Brother Kenneth C. Jack, Past Master, Lodge St. Andrew, No. 814, Pitlochry |

Sir Francis Bacon and Salomon’s House Does Sir Francis Bacon's book "The New Atlantis" indicate that he was a Rosicrucian, and most likely a Freemason too? Article by Kenneth Jack |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.4 The final part in the serialisation of George Blackie's 'History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order' transcribed by Kenneth Jack. |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.3 Third part in the serialisation of George Blackie's 'History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order' transcribed by Kenneth Jack. |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.2 Second part in the serialisation of George Blackie's 'History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order' transcribed by Kenneth Jack. |

George Blackie – The History of the Knights Templar P.1 First part in the serialisation of George Blackie's History of the Knights Templar and the Sublime Teachings of the Order – by Kenneth Jack |

Little known as a Freemason, Bro Dr Robert ‘The Bulldog’ Irvine remains a Scottish rugby legend, and his feat of appearing in 10 consecutive international matches against England has only been surpassed once in 140 years by Sandy Carmichael. |

Rev. J.B. Craven: Theologian, Historian, Freemason, And Rosicrucian Scholar Archdeacon James Brown Craven is one of those unsung heroes of Scottish Freemasonry about whom very little has been previously written – here Kenneth Jack explores the life and works of this remarkable esoteric Christian. |

Discover the powerful family of William Schaw, known as the 'Father of Freemasonry' |

This month, Kenneth Jack invites us to look at the life of Sir William Peck; - astronomer, Freemason and inventor of the world's first electric car. A truly fascinating life story. |

A Tribute to Scotland's Bard – The William Robertson Smith Collection With Burns' Night approaching, we pay tribute to Scotland's most famous Bard – The William Robertson Smith Collection |

The Joy of Masonic Book Collecting Book purchasing and collecting is a great joy in its own right, but when a little extra something reveals itself on purchase; particularly with regards to older, rarer titles.. |

Masons, Magus', and Monks of St Giles - who were the Birrell family of Scottish Freemasonry? |

The 6th Duke of Atholl - Chieftain, Grand Master, and a Memorial to Remember In 1865, why did over 500 Scottish Freemasons climb a hill in Perthshire carrying working tools, corn, oil and wine? Author Kenneth Jack retraces their steps, and reveals all. |

Charles Mackay: Freemason, Journalist, Writer Kenneth Jack looks at life of Bro Charles Mackay: Freemason, Journalist, Writer, Poet; and Author of ‘Tubal Cain’. |

A Mother Lodge and a Connection Uncovered, a claim that Sir Robert Moray was the first speculative Freemason to be initiated on English soil. |

What is it that connects a very old, well-known Crieff family, with a former President of the United States of America? |

The life of Bro. Cattanach, a theosophist occultist and Scottish Freemason |

The Mysterious Walled Garden of Edzell Castle Explore the mysterious walled garden steeped in Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and Hermeticism. |

Dr. George Dickson: Scottish Freemason and Occultist Bro. Kenneth explores the life of Dr George Dickson a Scottish Freemason and Occultist |

The Colour Purple - Its Derivation and Masonic Significance What is the colour purple with regards to Freemasonry? The colour is certainly significant within the Royal Arch series of degrees being emblematical of Union. |

Bridging the Mainstream and the Fringe Edward MacBean bridging mainstream Freemasonry with the fringe esoteric branches of Freemasonry |

Freemasonry in the Works of John Steinbeck We examine Freemasonry in the Works of John Steinbeck |

Renegade Scottish Freemason - John Crombie Who was John Crombie and why was he a 'renegade'? |

Scottish Witchcraft And The Third Degree How is Witchcraft connected to the Scottish Third Degree |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device