“To this day there is hardly a public meeting of religious people of the shires of Fife, Perth, or Angus, in which the destruction of the Gowries, when it is mentioned, is not always regarded with horror and disgust.”

~Rev. James Scott (1818)

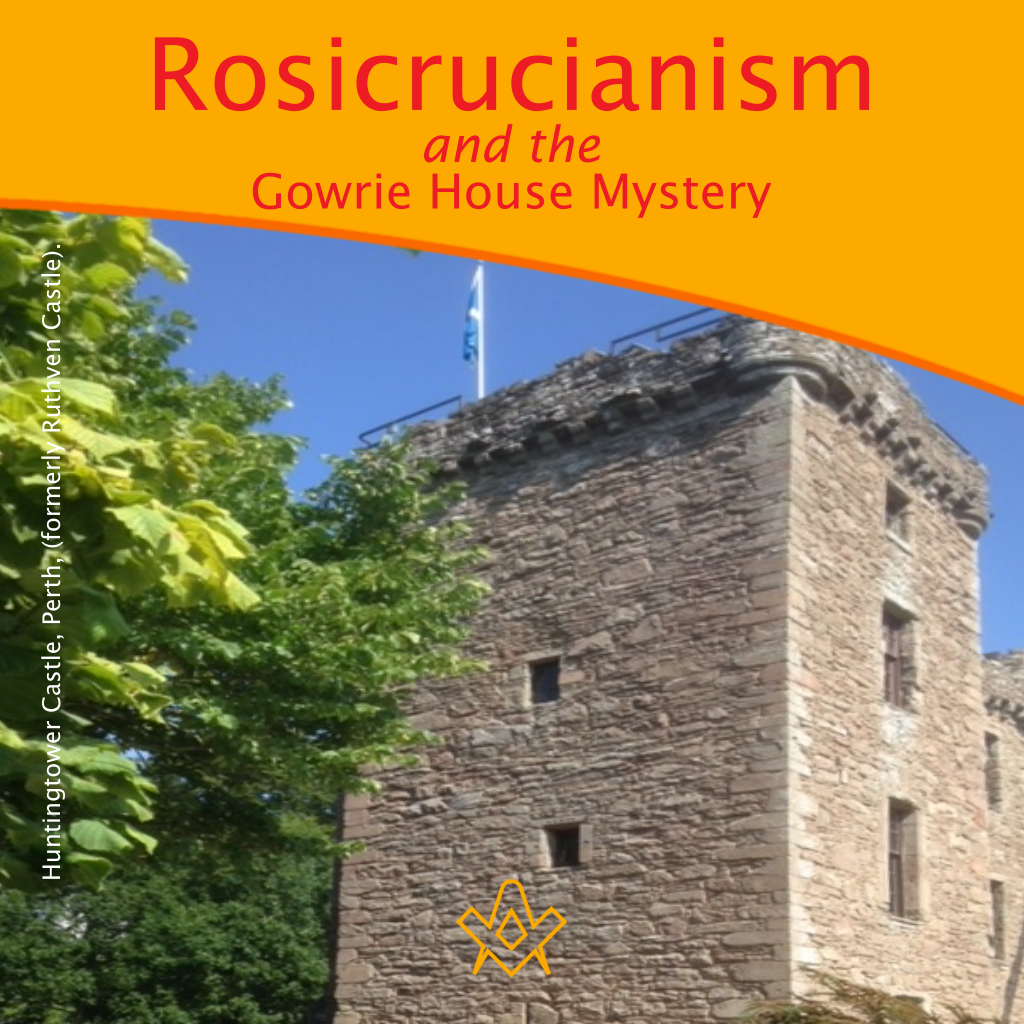

THE GOWRIE HOUSE MYSTERY OF 1600, AND THE EVOLUTION OF FREEMASONRY

By Brother Kenneth C. Jack, Past Master, Lodge St. Andrew, No. 814, Pitlochry.

The following paper is speculative in nature. Whilst much of the information contained within it is grounded on sound historical evidence, the main thesis and conclusions are solely those of the author.

In gambling parlance, it is said that you have to: ‘speculate to accumulate’, and it is this principle which the present writer employs here.

The paper should provoke discussion, and further research into a fascinating subject, which has interested and bemused Masonic and historical researchers for many years.

In the paper, the author tantalisingly suggests that sacred knowledge was discovered by a nobleman from Perth in continental Europe in the late 16th century and was brought by him back home to Perth, where it was purloined by James VI and members of his court, in the course of a murderous event in Perth, Scotland, on 5 August 1600.

It was thereafter entrusted into the care of local Brethren of the Rosie Cross, or indeed Freemasons, during a time in which stonemason lodges were becoming ever more speculative in nature.

HENRY ADAMSON AND ROSICRUCIAN PERTH

For what we do presage is not in grosse,

For we be brethren of the rosie cross;

We have the mason-word and second sight,

Things for to come we can foretell aright.”

Most Freemasons throughout the world are now familiar with the foregoing lines, which are regarded as containing the first written reference to the Mason Word. The lines are from a metrical history of Perth, Scotland, by a poet from the city, Henry Adamson.

The lengthy poem known as The Muses Threnodie was published at Edinburgh in 1638, although the author was prompted to do so sometime earlier by his friend and famous fellow poet William Drummond of Hawthornden.

These verses from the third muse are interesting in the fact they appear to synthesise several subjects, namely: The Brethren of the Rosie-Cross (Rosicrucians), the Mason Word (Freemasons), and second-sight, (the occult Art of Memory).

These are the lines which most Masonic scholars focus on, for obvious reasons; but the following lines are equally interesting:

And shall we show what misterie we mean,

In fair acrostricks Carolus Rex is seen,

Describ’d upon that bridge in perfect gold,

By skilfull art this cleerlie we behold,

With all the scutcheon of Great Britain’s king,

Which unto Perth most joyfull news shall bring.

Loath would we be this misterie to unfold,

But for King Charles’ honour we are bold.

This is clearly Adamson and his Brethren of the Rosie Cross expressing their support of King Charles I, who is known to have been a staunch defender of the Rosicrucians in Britain.

Elsewhere in the Muses are lines which might provide a clue to what Adamson meant by the gift of second-sight, and the ability to foretell the future. In the sixth muse, he writes:

There we beheld where Wallace ship was drowned,

Which he brought out of France, whose bottom found,

Was not long since, by Master Dickson’s art,

That rare ingeniour, skill’d in every part of Mathematics.

Adamson pens these lines in describing a sailing trip on the river Tay in Perth, and the reference to Master Dickeson is likely a reference to Alexander Dickson, a known proponent of the Art of Memory, and a student of the famed Italian hermetic philosopher Giordano Bruno.

Dickson, whose surname has been spelt in a variety of ways, was a courtier to King James VI of Scotland, as were other known proponents of the Art such as William Fowler; and the reputed father of speculative Freemasonry William Schaw.

‘Master Dickeson’s Art’, must therefore be a reference to the Art of Memory, an art which was apparently of sufficient import as to be capable of locating a long-lost sunken ship in the river Tay.

This combined with the gift of second-sight evidently held by the Brethren of the Rosie Cross, is indicative of two things: that the said brethren had occult powers, and that Alexander Dickson may well have been one of their number.

It also suggests that Perth was a hotbed of Rosicrucianism; not necessary exclusively so, but given the details related in Adamson’s metrical history of the city and other events to be related hereafter, it may have been key to the development of Rosicrucianism, and a later esoteric society; the Freemasons.

As indicated earlier, this paper will propose a controversial theory, which suggests that Adamson’s ‘Mason Word’, may in fact have first come to the fore in the city of Perth, as a result of an incident which occurred there on 5 August 1600.

The incident involved no less than King James VI of Scotland, and a family of local noblemen by the name of Ruthven.

THE RUTHVEN FAMILY

The Ruthven family of Perthshire are said to be descended from Thor, Lord of Tibbermore, an estate on the outskirts of Perth. He was a nobleman, of either Saxon or Danish origin, and lived in Scotland during the reign of King David I, and possibly also, Malcolm IV.

Thor first owned the Ruthven family seat of Ruthven Castle (now Huntingtower Castle), and he built chapels both at the castle and Tibbermore, dedicating the former to St. Peter, and the latter to the Virgin Mary.

His son, Swaine, fell heir to the lands of Tibbermore and Ruthven and for much of his life, lived under the rule of the famous William the Lion.

Swain’s grandson, Sir Walter of Ruthven, was the first member of the family to assume the family surname in 1245.

It is unnecessary for the purposes of this paper to detail the full genealogy of the Ruthvens, details of which can be obtained from published histories of the family, so we shall proceed to the 16th century, and discuss a Ruthven family connection which may have inadvertently led to a mysterious and murderous incident in Perth, which historians still puzzle over.

Margaret Tudor (1489-1541)

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Margaret Tudor was born on 28 November 1489, and was the eldest daughter of King Henry VII of England, and Queen Elizabeth Plantagenet.

Margaret married King James IV of Scotland at Holyrood House Edinburgh, on 8 August 1503, when only thirteen years of age. James IV was killed at the Battle of Flodden in 1513, and the only surviving son from the marriage became James V. Eleven months later, Margaret married Archibald Douglas, who was known as the ‘Great Earl of Angus’.

As a result of the death of her first husband, she no longer had royal duties as regent of the Kingdom but was keen to retain some power and influence through her son.

Despite opposition from her brother, King Henry VIII, Margaret divorced the Earl of Angus, her apparent reason for doing so, being she had learned that her husband had previously married a daughter of the Baron of Traquair, with whom he had a daughter, Lady Jean Douglas.

Margaret required the divorce in order to marry her third husband Henry Stewart, second son of Andrew, Lord Evandale and Ochiltree. She succeeded in obtaining for her future husband the offices of: Gentleman of the Bedchamber to the King, General of the Artillery, and Director of the Chancery.

In 1528, the King granted his mother and her latest husband, Henry Stewart, the ‘whole lands’ of Methven and Balquidder, and by a royal patent later that year, the King awarded Henry a peerage, raising him to the title of Lord Methven.

As a result of this, the Queen and her husband took up residence at the Castle of Methven, only a few short miles west of Ruthven Castle, the home of the Ruthven family.

Lord Methven had a daughter named Dorothea Stewart, but historians have been unable to confirm this was with Queen Margaret, as she may have been born to his later wife, Lady Jane Stewart.

Margaret died in Methven on 18 October 1541, and was buried in the Charterhouse at Perth.

In around 1544, Lord Methven married Lady Janet Stewart, the daughter of John Stewart, the second Earl of Atholl, becoming her third husband. Lord Methven is believed to have died about 1554, whereupon Lady Janet married Patrick, the third Earl Ruthven.

As it happens, Patrick Ruthven, had been previously married to the aforementioned Lady Jean Douglas with whom he had a large family. He was much younger than Lady Jane Stewart, and it is considered she was too old to have any issue with him.

Patrick’s son William, by his previous marriage to Lady Jean Douglas, became the fourth Lord Ruthven, and the first Earl of Gowrie.

William married Lord Methven’s daughter, Countess Dorothea Stewart, on 17 August 1561, and they had a very large family which included second and third sons respectively: John and Alexander.

His first son James became the second Earl of Gowrie, but following his premature death, he was succeeded by brother John, who became the third Earl of Gowrie. Rather a tangled web, and, as said, it is a bone of contention amongst historians, whether Countess Dorothea Stewart was the daughter of Queen Margaret by her marriage to Lord Methven, or whether she was born to Lord Methven and subsequent wife, Lady Jane Stewart.

If the former, then John Ruthven, third Earl of Gowrie, was grandson of Queen Margaret, and held a legitimate claim to the crown of England.

If the latter, he was allied to the Scottish royal family. This fact should be borne in mind when we subsequently consider that it is John, the third Earl of Gowrie, and his brother Alexander, who became the main players in the unresolved mystery that would unfold in Perth on 5 August 1600. [1]

THE RUTHVEN FAMILY AND THE OCCULT

“For several generations the leading Ruthvens were not merely men whose talent led them specially toward the study of those mysteries of chemical philosophy which ignorance and prejudice have, too often confounded with sorcery and magic, a cry was raised on this score by their political opponents, successively against Patrick, Lord Ruthven, and his son, the first Earl of Gowrie, when was Iain in the proofs given on the Gowrie Conspiracy, upon a paper covered with unknown characters, which was found in the pockets of the third Earl, Bishop Barnet gravely records, as we have seen, that it was given out of Patrick Ruthven’s older brother William, that ‘he had the Philosopher’s Stone’.”

~John Bruce (1867)

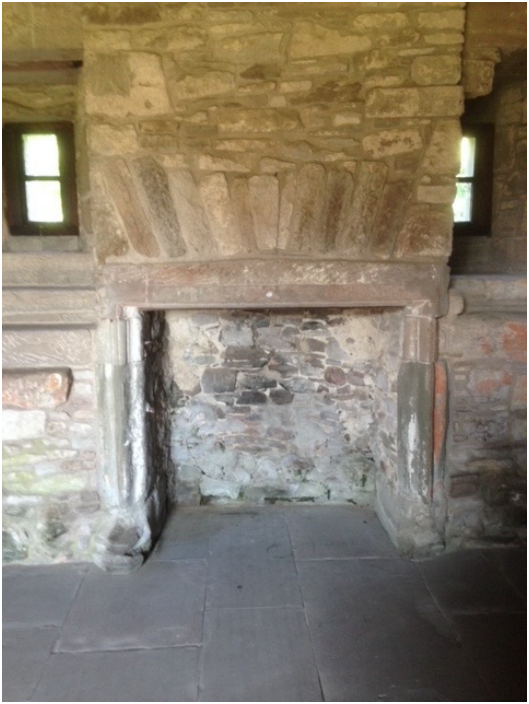

Interior view of Huntingtower Castle.

IMAGE CREDIT: author’s collection

The former home of the Ruthven Family on the western outskirts of Perth, still stands proudly today, and as a local tourist attraction receives a number of visitors from around the world.

However, following the demise of the Ruthven family, the family stronghold’s name was changed from Ruthven Palace to Huntingtower Castle.

The property and estates of the family were disbursed among friends and supporters of King James VI, mainly to ‘gentleman by the surname of Murray’.

The walls of the castle were subsequently overlaid with woodwork by the new owners, but centuries later during archaeological work, the wood was stripped, and underneath was revealed various pieces of artwork, which stand as testimony to the alchemical interests of the family.

Chief of these is a painted image on the ceiling of one of the main rooms of a green lion devouring the sun, a very well-known symbol of the alchemical process.

In a window frame of the same room there are images of the biblical Adam; an angel; and a hare running between them. The hare was an alchemical emblem for mercury, and the image appears to represent either the fall of man from his original divine state, or indeed, his regeneration back to that divine state.

Alchemical imagery from interior of Huntingtower Castle, Perth.

IMAGE CREDIT: author’s collection

Probably the most prolific alchemists in the family were the aforementioned William and Patrick. William was reputed to have the alchemists’ Holy Grail, the ‘Philosophers Stone’.

Patrick Ruthven’s alchemical notebook, known as his commonplace book, is preserved at the University of Edinburgh, and contains much correspondence, diagrams, tables, symbols, and information on various alchemical processes; which clearly highlight his knowledge of the art; both in a practical, but perhaps more importantly for this discussion, a spiritual sense. [2]

As will be demonstrated, their brother John, the third Earl of Gowrie, also had an extremely keen interest in occult subjects, and it is proposed that this interest, may have been at least one of the reasons behind the incident which took place in Perth, and which has aptly been described ever since, as the ‘Gowrie House Mystery’. Mysterious indeed, by dint of the fact no one has ever satisfactorily resolved it.

KING JAMES VI AND FREEMASONRY

“So, as your Majesty stands invested of that Triplicity, which in great Veneration was ascribed to the antient Hermes; the power and fortune of a King; the knowledge and illumination of a Priest; and the Learning and Universality of a Philosopher.”

~ Sir Francis Bacon’s tribute to King James VI & I.

Some imaginative commentators consider King James VI of Scotland (James Charles Stuart) to have been a Freemason, reputedly having been initiated into Lodge Scoon & Perth, No. 3, Perth, Scotland, on 16 April 1601.

He is variously described as the ‘Masonic King’, and ‘King Solomon in the North’. However, this claim is largely based on the so-called mutual agreement, drafted at a time when Lodges in Scotland were vying for their place on the Roll of the Grand Lodge of Scotland.

The Lodge commissioned a history which helped support this claim, and as the foregoing implies was agreed by all concerned; and Scoon & Perth were allocated their place on the Roll.

However, as many historians argue, there are no minutes, or records extant, which confirm any such admission to the Lodge; and as late Scottish Masonic historian, Bro. Edward Macbean stated, claims of the King’s admission to this Lodge are purely ‘apocryphal’.

In claiming this, Macbean would be mindful of the fact, that speculation was anathema to his contemporaries, who were rigidly of the ‘authentic’ school of Masonic research.

Notwithstanding, it cannot be denied that the King was a regular visitor to the important town of Perth, a fact recorded in contemporary records of the time. [3]

Whilst it remains unproven, the possibility of the King becoming a Freemason in Perth- or indeed elsewhere, cannot be totally discounted.

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland succeeded Queen Elizabeth I, and ascended to the throne of England and Ireland, in the process becoming King James I.

It is probably safe to assume he retained his esoteric interests in England and had a hand in the transition from operative to speculative masonry in that country.

An interesting account exists of what is described as a form of pageant, held at the home of the English nobleman, the Earl of Salisbury in 1606.

A great feast was held at his stately home at Theobolds in Hertfordshire, on behalf of his guests: King James VI & I, and the visiting King of Denmark, Christian IV.

The pageant consisted of a re-enactment of the visit by the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon’s Temple. It appears that despite best intentions, the pageant rather deteriorated due to the over consumption of alcohol.

The lady who played the Queen, dutifully brought gifts to the assembled sovereigns, who were seated under a canopy on a form of stage.

Unfortunately, the ‘Queen’ tripped on the steps up to the stage and succeeded in decanting her gifts into the lap of the Danish King and falling at his feet. As the gifts included the likes of wine, cream, jelly, beverage, cakes, and spices, a mess was made, which required to be mopped up quickly.

The King of Denmark then got up to dance with the ‘Queen’ but fell down drunk and had to be carried off to his bed. Three ladies representing the three great virtues: Faith, Hope, and Charity, then entered and attempted to make speeches, but they were also under the influence of wine, and had to bid their leave to vomit in the ‘Lower’ Hall.

Ladies representing Victory, and Peace, also made less than successful appearances, and the whole affair appears to have degenerated into a debauched, drunken charade. One can only hope and trust that this was not some form of proto-Freemasonry gone awry. [4]

Whether he was a Freemason or not, when it comes to the incident at Gowrie House in 1600, one must bear in mind that at that time, Scotland was a suspicious- and a superstitious country.

James VI warned his people against the dangers of witchcraft and black magic in a book he published in 1597 entitled ‘Daemonologie’. In his preface to this work he states:

The fearful abounding at this time in this countrie, of these detestable slaves of the Devill, the Witches or enchanters, hath moved me (beloved reader) to dispatch in post, this following treatise of mine, not in any way (as I protest) to serve for a shew of my learning and ingine, but onely (moved of conscience) to preasse thereby, so farre as I can, to resolve the doubting harts of many:

both that such assaultes of Sathan are most certainly practised, and that the instruments thereof, merits most severely to be punished: against the damnable opinions of two principally in our age, whereof the one called Scott an Englishman, is not ashamed in publike print to deny, that there can be such a thing as Witchcraft: and so mainteines the old error of the Sadducees, in denying of spirits.

The other Vierus, a German Phistion, sets out a publick apologie for all these craft-folks, whereby procuring for their impunitie, he plainely bewrayes himself to have bene one of that profession.

The King’s book takes the form of a dialogue and is divided into three sections covering: Magic and Necromancy; Sorcery and Witchcraft; and Evil Spirits, with a conclusion at the end of the book. The King ends his preface by stating:

If he would know what hath bene the opinion of the Auncients, concerning their power: he shall see it well described by Hyperius, and Hemmingiue, two late German writers: besides innumerable other neoterick Theologues, that writes largelie upon that subject; and if he would knowe what are the particular rites, and curiousities of these black arts (which is both unnecessary and perilous), he will find it in the fourth book of Cornelius Agrippa, and in Vierus, whomof I speak.

The King was probably describing not only Black Magic and Sorcery, but also the subject of Alchemy, practitioners of which in that day were wrongly accused of Necromancy and other evil doings.

Notwithstanding, we know that members of the King’s Court were interested in the subject of Alchemy, and that the King was schooled by some of them in the magico-religious ‘Art of Memory’.

There was precedent for Royal interest in occult subjects. The Rev. James Brown Craven; a noted Scottish 19th century religious scholar and historian observed:

At a still more remote time King James IV is said to have pursued occult studies, and in a letter to Mr James Ingles thanks him ‘for intimating to us that secret books, containing the sounder philosophy of Alchemy are in your possession’- sought for by others, but kept for the King’s use [5]

This sort of hypocrisy was common, for James VI also railed against the practice of sodomy, all the while allegedly taking himself a number of male lovers. It was a hypocrisy that would be evident once again, following the demise of the Ruthven family.

THE RUTHVEN FAMILY AND JAMES VI

To say that the Ruthven family had a chequered and troubled history with James VI would be somewhat of an understatement.

Prior to the incident at Gowrie House, there were two previous episodes in that relationship. In 1566, Patrick, third Lord Ruthven, and his son William, the fourth Lord, and the first Earl of Gowrie, were both implicated in the assassination of David Rizzio, a secretary and confidante to Mary, Queen of Scots, King James VI’s mother.

Both fled to England, where Patrick died soon after, but William returned to Scotland having made his peace, and subsequently supported King James.

In 1581, aforesaid William opposed Mary’s restoration to the crown of Scotland, and in the same year was involved in a further episode which came to be known as the ‘The Raid of Ruthven’.

This ‘Raid’ was both a political and religious enterprise, resulting from the private quarrels of certain noblemen, and interference from the clergy. James VI was noted for having his favourites, and rivals for this were the Duke of Lennox and the Earl of Arran.

As ever, religion played an important part, as members of the Protestant and Catholic elite vied for the King’s attention.

There must have been a fear amongst the Protestants that the teenage James could fall into the hands of the Catholics and go over to his mother’s religious affiliations.

One of the principal architects of this plot was the aforementioned William Ruthven, a member of one of Scotland’s most staunch Protestant families.

Although the stated aim was defence of religion and liberties of the country; the plotters were also hoping for the ruination of the Earl of Lennox.

On 22 August 1582, James was returning from a hunting expedition in Highland Perthshire, when he was invited to Ruthven Palace in Perth, by the Earl of Gowrie.

He stayed the night there, but was forcibly restrained from leaving the next morning, and was thus effectively abducted. He remained at Ruthven Castle for approximately one year, before being moved to Edinburgh, where he subsequently hatched his escape.

Gowrie and his confederates appeared to be forgiven this apparent act of treachery, but they continued to engage in plotting, and were subsequently arrested and put on trial for high treason. Despite maintaining that his actions were for the benefit of the King, Gowrie was found guilty and was beheaded. [6]

Despite this, a later generation of Ruthvens appear to have enjoyed a good relationship with King James VI. That is, until subsequent events at Gowrie House in Perth. Whether the aforementioned incidents had any bearing on subsequent events, we will perhaps never know, but possible motives will be discussed later.

JOHN, THIRD EARL OF GOWRIE

John Ruthven, sixth Lord of Ruthven, and third Earl of Gowrie, was the second son of William Ruthven, and his wife Dorothea Stewart, daughter of Henry Stewart, the first Lord Methven.

He was born around 1578, and at the age of eleven years, he succeeded to the title of Earl, following the premature death of his older brother James.

As indicated earlier, he was born into a staunch Protestant family, who had been firm supporters of the Reformation. As such, the young Earl was well drilled in the principles of that faith.

His education was entrusted to one Robert Rollock, Principal of the College of Edinburgh, who was described as ‘an able and pious divine, and author of some learned treatises’. He also had a private tutor by the name of William Rhind, a native of Perth, Scotland.

After an initial education in Perth, in 1591, he attended the University of Edinburgh, where he was graduated with a Master of Arts degree two years later.

During this time, at a still tender age, he was made Provost of Perth, following a number of other family members in that administrative post.

In 1593, perhaps encouraged to display the family’s rebellious streak, as evinced in earlier episodes, he joined his brother-in-law, John Stewart, Earl of Atholl, and Francis Stewart, the Earl of Bothwell, in a further effort to forcibly dissuade King James VI from showing partiality towards the Catholic Earls of Scotland.

The King defeated this group in battle in October 1593. The King appears to have put young Gowrie’s sedition down to his youth and the undue influence of others, and he was forgiven.

In August 1594, the Earl intimated to the town-council of Perth that he intended to further his studies abroad. In a show of respect to the Ruthven family, the council resolved to vote him into office as Provost annually, until he returned home.

One of the witnesses attesting to this was Patrick Galloway, a former church Minister in Perth, now one of the King’s Chaplains, but still a frequent visitor to the town. Galloway would have a crucial part to play in later events.

Ruthven left Perth on 6 August 1594, accompanied by his travelling tutor William Rhind. Most sources are silent on the matter, but others suggest the Earl’s brother, Alexander, Master of Ruthven, travelled with them. [7]

The party travelled via France, to the University of Padua in Italy, and thus commenced a very interesting period in the Earl’s life.

The University was famous for the quantity and quality of its professors, spread over ten colleges. In an indication of his good relationship with the King at this period, the Earl sent a letter to King James notifying him of his arrival at the University, and of the subjects he intended to study there. The King sent him a warm and affectionate reply.

Ruthven replied to this letter from the King, and in his letter dated at Padua, September 24 1595, he emphasised his respect, obedience, and affection for the King. Later historians would seize on this letter as evidence that Gowrie wished the King no harm. [8]

During this time, Gowrie developed an interest in occult matters. The Rev. J.B. Craven stated:

But one of the attested scholars of his day is better known, John, Earl of Gowrie. When a young student at Padua, if not at Rome, he went deeply into esoteric lore. The family of Ruthven had indeed been known for some generations as students of the mysteries of chemical philosophy, which ignorance and prejudice too often confounded with sorcery and magic. [9]

Craven briefly alludes to the controversy at Gowrie House, and the claims and counter claims made regarding events there:

It is sufficient to state that John Lord Gowrie had, when at Padua, became acquainted with a man, ‘and first hearing by report that he was a necromancer, and thereafter being informed that he was a verie learned man, and a deepe theologue, he entered in further dealings with him, anent the curiosities of Nature’.” [10]

The ‘divine’ who Ruthven encountered at Padua has never been identified, but it is instructive to note that also studying at Padua at precisely the same time, was a German alchemist and mystic by the name of Michael Maier.

Maier arrived In Padua in autumn 1595, and registered as a student at the university on 4 December that year. Ruthven arrived at Padua around this time-as evidenced by his exchange of letters with the King. Gowrie was still at Padua in 1597, for on April 19 of that year, he enrolled at the universitas luristarum (School of Law) there. [11]

It is thought he left the establishment in 1598. In 1595, John Ruthven was but a callow, impressionable youth, 17 years of age.

Maier’s published alchemical works, and discernible interest in Rosicrucianism, remained in the future, but it is inconceivable, that as a mature student, almost 30 years of age, that he had not already studied at length, matters of an esoteric nature.

Given the known predilection of both men for pursuing such interests, it is more probable than not, that they were acquainted whilst in Padua. This is highly significant, as scholars have long searched for such a connection. [12]

Maier studied philosophy and medicine at Padua sometime between 1595 and 1596, but left abruptly after getting involved in a fight in which his opponent was wounded.

In the years between 1590 and 1609 some 3145 German students are thought to have visited Padua. At some stage, post-1600, Maier reputedly joined the Brethren of the Rosie Cross, the Rosicrucians; an elusive sect, who in the early years of seventeenth century Germany, promulgated the so-called Rosicrucian manifestos, chief of which were the: Fama Fraternitatis, Confessio, and Chymische Hochzeit (Chemical Wedding).

Maier’s status as a Rosicrucian has been debated by historians, but whether he was or not, he may rightly be termed a ‘Rosicrucian apologist’, one of his most noted works being: Themis Aurea: The Laws of the Fraternity of the Rosie Cross.

In this work, published in 1618, he lauds the brotherhood in having:

“the true Astronomy, the true Physics, Mathematicks, Medicine, and Chymistry, by which they are able to produce rare and wonderful effects.” [13]

The Rosicrucian manifestos are widely considered to have been anti-Papal, bound up in an effort to secure freedom of worship, and to emancipate society from perceived religious oppression and dogma, forced by the worst excesses of the Roman Catholic church.

As such, the documents were very much in step with sentiments fueling the Protestant Reformation. As advocates of such policy, there is no doubt Maier and Ruthven would have considered themselves kindred spirits, and they would undoubtedly share knowledge of a more occult or esoteric nature.

Ruthven displayed an interest in natural philosophy at Padua, and was known to carry around in his pockets, scientific notes, symbols and characters, which he used to assist him in his studies into chemistry and sundry subjects.

These would be the cause of much speculation and conjecture following the later incident at Gowrie House in Perth.

It may also be instructive to note Ruthven spent three months with the famous Protestant reformer, Theodore Beza, during his return journey to Scotland, having obtained a letter of introduction prior to leaving his native country.

Ruthven arrived in England around December 1599, where he remained for a couple of months, during which time he gained the favour of an audience with Queen Elizabeth I; a fact which would not go unnoticed by the King in Scotland.

John Ruthven returned to Scotland at the end of February 1600, arriving home to Perth on 20 May. [14]

He had been out of Scotland barely six years; isolated from the intrigues of Scottish politics; and yet, as he set foot back in his native town, little could he have realised he had but a few short months to live.

THE GOWRIE HOUSE MYSTERY

“And the last thing concerns you that are his people; I exhort you, in the name of God, to think reverently of your Prince: remembering that Solomon binds your consciences not to speak ill of him, even in your secret chambers.”

~Rev. William Cowper, Perth.

On 5 August 1600, an incident occurred at Gowrie House, Perth, which resulted in the deaths of two of the Ruthven family: John Ruthven, third Earl of Gowrie, and his brother, Alexander Ruthven.

Many pages have been written about this affair, which has been called, ‘The Gowrie House Massacre’, or ‘The Gowrie House Mystery’.

The present writer prefers the term ‘mystery’, as there is little doubt no-one has ever been sure of the true reasons for what transpired that day.

There are two main theories, either that:

King James VI attended in Perth that day for the express purpose of ridding himself of the two brothers, or:

that the Ruthvens lured the King to Perth on a pretext, in order to abduct or kill him.

The present writer will advance a plausible theory concerning the incident, based on documented history, and suggest that the mystery is inextricably linked to another ‘mystery’ from the same time period.

As in all murder cases there has to be a motive, and in the case of King James VI, the following motivations have been put forward:

1. The King had the expectation of succeeding to the crown of England and Wales on the death of Queen Elizabeth the first.

2. The King was concerned that the elder Ruthven, John, third Earl of Gowrie had a possible legitimate claim to the throne due to his being the grandson of Queen Margaret Tudor.

3. On his return home from Padua, Italy, John had been received by Queen Elizabeth in England, who apparently took kindly to him, and would have likely been impressed by his staunch adherence to the Protestant faith; a confidence she would not necessarily have in James VI, who often favoured the catholic Earls in Scotland, and whose mother was the Catholic, Mary Queen of Scots.

4. The King was apparently indebted to the Ruthvens to the sum of £80,000.[15]

5. There were the previous plots and intrigues involving members of the Ruthven family.

6. The King suspected his wife may have had an affair with Alexander Ruthven.

Quite a lengthy list of motives there for King James VI to rid himself of the Ruthvens. When one comes to consider what might have motivated the Ruthvens to abduct or kill King James VI, the list is considerably shorter.

It might be the case that the Ruthvens did indeed have designs on the English crown, and perhaps felt that their Protestant credentials might make that a real possibility.

Some historians have pointed to the fact that whilst in Padua, Italy, John Ruthven designed for himself a form of heraldic design which consisted of an arm bearing a sword, piercing a crown; and of course, the Ruthvens had been involved in previous intrigues against the King.

Notwithstanding, at the time of the incident at Gowrie House, there is no real evidence that the Ruthvens were plotting against the King, and historians point to the mutually affectionate tone of the correspondence between John Ruthven and the King in 1595 whilst the former was in Italy.

It is not the purpose of this paper to relate in every small detail the incident which took place at Gowrie House; but the account which was largely accepted at the time, was effectively the King’s own account, corroborated by his supporters.

Over the years, this narrative has been disputed by the Ruthven family and their supporters, and eminent historians have adopted opposing views on the matter.

In order to forward his own thesis, the present writer will simply summarise events, taking into account both versions of the incident. For a fuller account, the reader may be referred to the many histories which have been written throughout the years.

Gowrie House was demolished in 1870, but once stood near the River Tay, at the foot of South Street in Perth, in an area partly occupied in the present day by Perth Sheriff Court.

It was a large town house. It had been built in 1520 by the Countess of Huntly, and subsequently purchased by the Ruthvens. The Ruthven family had three prime homes in Perthshire: Ruthven Palace, Trochry Castle in Dunkeld, and Gowrie House.

Around Thursday, 31 July, or Friday, 1 August 1600, John Ruthven, and his brother Alexander arrived at Gowrie House in Perth, following a trip to their home in Highland Perthshire.

It had apparently been the Earl’s intention to travel to another family home at Dirleton in East Lothian on Tuesday, 5 August, to ask his mother to reside for a period with him in Perth.

On the evening of Monday, 4 August 1600, the Earl and his brother were surprised to receive a letter from King James VI, requiring Alexander to be at Falkland early the next morning. The King was residing at his palace in the small Fife village at this time.

Alexander was apparently very reluctant to go, as he believed he was not in favour with the King. This might have had something to do with the King’s suspicions about Alexander’s relationship with his wife.

However, Alexander decided it best to comply with this instruction, and went to Falkland. The Earl deferred his proposed trip in order to await word on his brother’s reception from the King.

Alexander apparently received a warm welcome from James, who invited him to go deer-hunting with him.

It was during his time with the King that Alexander is purported to have invited the King to come to Perth to see a man there who was in possession of what has variously been described as gold or treasure.

This appears to be rather a ludicrous proposition in the circumstances, and has been seized upon by Ruthven supporters as a spurious attempt by the King to justify going to Perth; especially since Alexander was also reported as saying his brother, the Earl, had no knowledge of this man.

It should be noted in passing, that there were individuals in those days, who went around purporting to have the ability to turn base metals into gold; reputed ‘alchemists’ whose efforts were never successful, but could turn the head of a grasping Monarch.

However, it may be, that it was not material gold which interested the King, but perhaps something even more alluring than that. The King may have been tempted to Perth by talk of ‘spiritual gold’.

To the surprise of his retinue, the King resolved to attend in Perth immediately to speak with the Earl of Gowrie. Alexander apparently tried to remonstrate with him, highlighting the Earl’s intention to travel to East Lothian.

He also tried to talk the King into allowing him to set off before him, in order to forewarn his brother of the King’s impending arrival; but all to no avail, as the King insisted he travel with him.

Whatever transpired between Alexander and the King, it appears that the King was determined to travel to Perth to see for himself who, or what, was reputedly detained there by the Earl of Gowrie.

The King and his fairly large retinue set out for Perth, and noting that Alexander looked rather pensive, the King asked Ruthven’s brother-in-law, the Duke of Lennox who was present, what he thought of his nature, and whether he was routinely pensive.

The Duke replied that he found Ruthven to be an “honest and discreet gentleman.” The King is then alleged to have said:

“You cannot guess man, the errand I am riding for. I am going to get a pose in Perth.”

The Duke replied that he did not like the tale the King had been given, and found it very unlikely. The King dismissed his concerns, stating:

“Take notice where I go with Mr Alexander, and follow me.”

This clearly demonstrates that the King had a design in mind, and that he fully expected Alexander Ruthven to lead him to something he was keen to see, and get his hands on.

When the King and his party were within a mile of Perth, Alexander Ruthven was permitted by him to ride ahead and alert his brother John of the King’s imminent arrival.

On Alexander’s arrival at Gowrie House, John Ruthven was entertaining dinner guests, another indication that he was not expecting the King.

At one o’clock, John Ruthven, as the Provost of Perth, along with other magistrates, and other important residents of the town went out onto the South Inch, a large green area, a stone’s throw from the Earl’s house, where they formally greeted the King.

Both parties then repaired to Gowrie House. By some accounts, John Ruthven was uneasy at the King’s presence, having some reason to believe the King was not particularly well-disposed towards him at that moment.

The Earl did not have much food in store for the King, and had to improvise by sending out for provisions. He apologised to the King for this, emphasising the short notice he had been given of the King’s visit.

It was an hour before the Earl was able to provide the King with a meal, and some have highlighted the fact that this provided ample opportunity for the King to be shown the strange man with the supposed pot of gold.

The fact there is no apparent mention of this during that period, leads some to conclude the mysterious man was an invention of the King.

If it was, one could be forgiven for thinking the King could have provided a more plausible explanation for attending Gowrie House. It might well be of course that there was a distorted element of truth behind what the King stated.

However, in his own account of the affair, the King averred that it was not his greed for gold that drew him to Perth, but the fact the mysterious man allegedly in possession of it, might cause ‘public mischief’.

In all likelihood, it was John Ruthven who was in possession of something which the King found troubling.

It is unnecessary here to describe in detail the plan of Gowrie House, but some knowledge of the location and topography of the house is helpful.

South Street in Perth runs from west to east, and the house was situated at the east end of the street, almost precisely where South Street intersects with streets known as Watergate, on its north side, and Speygate on its south side.

The main gateway to the house faced on to South Street and was situated near to the junction with Watergate. A garden wall ran along the front of the building towards Speygate. At the rear of the house was a garden which stretched eastwards to the River Tay which flows north to south behind the house.

On entering through the gateway, one entered a courtyard, and the main building was to the front and right, in the shape of an inverted L. The basement of the house contained domestic offices.

The main entrance to the house was situated at the angle of the inverted L, and one entered the house into a hallway; a door on the left led into a small dining-room; another to the right, led to the ‘Great Hall’, which in turn led to a large apartment room.

A door at the east end of the hallway led to a stairway out into the garden behind the house. An internal staircase led up to a room which was known as the ‘Great Gallery’. A door led from the great gallery into a room known as the ‘Gallery Chamber’.

Adjacent to the chamber was a small, circular-shaped closet room which the Earl used as his study, and which had a turreted roof.

This room had two windows, one which looked directly west into South Street, and the other north to the main gateway.

There was a stairway which led from the south-west courtyard up to the north or west door of the gallery chamber and the Earl’s study room.

This dark, narrow stair, was known as the ‘private’, or the ‘black turnpike’, and was used by the Earl as the quickest route to his study. [16]

The King sat down to dine in a hall in the north-east part of the building about two o’clock in the afternoon, and was apparently in high spirits, buoyed by the fact he had been joined by an armed retinue of men with whom he felt perfectly safe.

On the contrary, the Earl felt increasingly uneasy by this unwarranted and unexpected intrusion to his home. Once he had consumed his dessert course, the King intimated to Alexander Ruthven that he wished to retire to a private room.

This was expected, and the King had been allotted the Earl’s study for the purpose. Prior to leaving, the King apparently forced the Earl to drink to his health, which the Earl had neglected to do, contrary to established protocol, and there was clearly a strained atmosphere.

Whilst drinking the toast, the King’s courtiers observed the King and Alexander Ruthven walking at the far end of the hall.

The Duke of Lennox proceeded to follow them, but the Earl intervened saying that: “his majesty was going up quietly on a quiet errand.” The Earl then repaired to the garden with a number of other gentlemen.

Alexander Ruthven took the King upstairs and through the large gallery to the gallery chamber and the Earl’s study. Alexander was alleged to have locked the door between the gallery and gallery chamber in the course of a plot to kill the King, but it has also been reported that the Earl’s treacherous porter locked it at the behest of the King’s men, and afterwards gave the key to Sir Thomas Erskine.

It is suspected that a number of the King’s henchmen may have been posted in the Earl’s study in advance. Shortly after, a false report was put about that the King had left Gowrie House, which caused a commotion amongst his courtiers, who hastened for their own horses.

It is believed this false report may have been instigated by the Earl’s porter. The Earl did not believe his own porter, stating that all the exit gates were closed, and that he had the only keys for them.

The Earl made his way to his study, by the main route, and returned shortly stating that the King had gone. It is believed the Earl may have been deceived into thinking this, by those standing guard at the gallery chamber.

The opposing view is that he well knew the King was still present and that a plot was under way to abduct or kill him.

In any event, during the commotion, the King was able to make his way to a study window at the southwest of the building and leaning out, shouted for help, claiming treason, and that his life was being endangered.

He particularly sought assistance from the Earl of Mar, who was standing outside looking up at the window, in the company of the Duke of Lennox, and the Earl of Gowrie.

It has been said that at this time, Alexander Ruthven was seen grabbing hold of the King’s cheek, apparently in an effort to stifle his cries for help. Again, this can be viewed in two ways; either, Alexander was trying to harm the King, or, realising he was being set up, was acting in self- preservation.

At this point, the Earl was attacked by Sir Thomas Erskine, his brother James Erskine, and James’ servant, George Wilson, who clearly determined a treasonous act was being played out.

The Earl was saved from possible death at that point by his friends and servants, and is alleged to have exclaimed: “Oh, My God, what can all this mean?” Perceiving the threat to his life, the Earl ran to a nearby house where he obtained two swords for the use of he and his servants, before running back to the house.

In the meantime, Sir John Ramsay, the King’s Page, ran up the’ black and narrow turnpike’, and burst open a door leading into the room where the King was. He claims he saw Alexander Ruthven on his knees, the King grappling with him, and holding his head under his arm.

Notwithstanding, Alexander was apparently still trying to prevent the King from talking by covering his mouth with his hand.

Ramsay stabbed Alexander once with a dagger, at which point, another man, later tentatively identified as the Earl’s servant Andrew Henderson, ran from the room.

Ramsay, at the behest of the King, then stabbed Alexander in the neck and head. This is most curious, as it may be assumed, that by running off, Henderson had been acting against the King.

This, combined with the fact, Alexander Ruthven was younger and stronger than the King, would seem to belie the fact the King appeared to be relatively in control of the situation.

It has to be said that Henderson’s part in this incident has never been satisfactorily explained. On the other hand, like the Earl’s porter, Henderson might have been in the employ of the King and his men, and may have run off to conceal the fact.

Ramsay then shouted out the window to Sir Thomas Erskine beckoning him up to the room. Erskine, along with Dr. Sir Hugh Herries, and George Wilson ran up the turnpike staircase where they came upon a bleeding Alexander Ruthven.

Decrying him as a traitor, Sir Thomas commanded the other two to stab Alexander to death. With his dying breath, Alexander declared his innocence of any wrong-doing, blaming the King for what had just occurred.

Moments later the Earl arrived at the scene with his servant Thomas Cranston; they were both armed. After some objection, both were admitted. It has been said that the Earl stated: “Where is the King, I am come to defend him.”

Those present pointed to the dead body of his brother on the floor, one of them replying: “You have killed the King, our Master, and you will now take our lives?’

The Earl is reported to have pointed his two swords to the floor, and agonisingly exclaimed: “Ah, woe is me, has the King been killed in my house?”

At this point, Sir John Ramsay stabbed him in the heart with a sword or dagger. Both Ruthven brothers were now dead, and history has failed to establish whether they died as a result of a conspiracy by them to harm the King, or whether the opposite was true; that the King conspired to kill them, and rid himself of a perceived threat. [17]

News of the unfolding tragedy spread to the townspeople of Perth, and a large gathering of them appeared outside Gowrie House.

Many of them appeared to suspect foul play on the part of the King, and were angered at the apparent injustice meted out to the Ruthven brothers.

The King’s entourage considered it wise and expedient to remove the King from the area, and he was taken by the rear door of the house, through the gardens, to a waiting boat on the River Tay, which carried him down to the nearby South Inch, from where he was transported back to Falkland Palace. [18]

AFTERMATH

“And the LORD said unto him. What is that in thine hand? And he said. A rod.

And he said. Cast it on the ground.

And he cast it on the ground, and it became a serpent; and Moses fled from before it.

And the LORD said unto Moses. Put forth thine hand, and take it by the tail.

And he put forth his hand, and caught it, and it became a rod in his hand.”

~ Exodus 4: 2-4

We now arrive at the strangest part of this tragedy. In the immediate aftermath of the incident, the King and his cohort considered what account of the incident they should feed the public.

It was decided that the Ruthvens should be denounced as traitors and that their family estates be forfeited. The dead bodies of the Ruthven brothers were then searched.

In Alexander’s pockets was found the letter in which the King invited him to Falkland. This was apparently immediately destroyed. But what was considered “a great and important discovery,” was made by Sir Thomas Erskine. [19]

He took from the pocket of the Earl of Gowrie’s “girdle,” (belt) a small book, full of magical spells, and characters. These were discussed in a letter sent by Lord Cromarty to the printer James Watson, when trying to encourage him to publish an historical account of the Gowrie Conspiracy.

Cromarty wrote:

Royston, May XII, 1713

Sir,

I have been in search of these papers, found in the Earl of Gowrie’s girdle or belt, taken out of it after the Earl was killed at Perth.

They consist of two sheets stitched in a little book of near five inches long and three broad: full of magical spells and characters, which none can understand, but those who exercise that art, these papers I found in Sir George Erskine of Invertile’s cabinet, wrapt (sic) in paper, whereon was writ with Sir George’s on hand, ‘These are the papers which Sir Thomas Erskine, my brother did take out of the Earl of Gowrie’s girdle after he was killed at Perth, and which papers was then delivered by my Brother Sir Thomas to me to be kept’.

These papers I cannot now fall on, tho’ I am certain I have them by me. But I declare in faith and honour, I did find them in manner foresaid, and have many times shown them to others, in above sixty years’ time, and therefore, I desire that you may put an end to the book and publish it.” [20]

Your friend, Cromarty.

It was alleged, by those present at his death, that while this girdle was on the Earl’s person, the wounds from which he died did not bleed.

However, when the girdle was taken from him, they bled profusely. This may have been another attempt to besmirch the Earl’s name, by ascribing some magical component to the book found in his possession.

However, more sober minds have also suggested that if the Earl had been run through by a slender rapier type sword, then his wounds would have bled inwardly, before eventually gushing outwards.

In the days following the incident at Gowrie House, it transpired that a significant number of clergymen in Edinburgh were reluctant to accept the guilt of the Ruthvens without further proof, and were suspicious of the King himself, and refused to offer public thanks to God for his safety.

As a result, the King ordered that they should not preach anywhere within his kingdoms under pain of death, and were ordered to leave Edinburgh within 48 hours.

During their absence, Perth Minister, the Reverend William Cowper, was summoned to Edinburgh to preach for a day. His sermon was largely positive towards the King, and at one part of it he stated:

And the last thing concerns you that are his people; I exhort you, in the name of God, to think reverently of your Prince: remembering that Solomon binds your consciences not to speak ill of him, even in your secret chambers. [21]

Although there is a danger of reading too much into such things, one could be forgiven for thinking that in his use of the words: “You that are his people,”; “Solomon,”; and “Secret Chambers,” Cowper was deliberately addressing the Masons of the country.

Of course, if the King himself ever did become a Mason, certain tradition informs us that it was not until the following year 1601.

A number of people were questioned concerning the strange letters and characters found in the earl’s possession at the time of his death.

The King’s side used the find of these so-called magical characters as evidence of the fact the Earl was a sorcerer or black magician, which would of course play nicely into the Kings narrative in portraying the Earl in an evil light.

One of the prime movers in pushing this narrative was the aforementioned Reverend Patrick Galloway, who was amply rewarded for his services by the King.

In a sermon preached at the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh on 11 August 1600, Galloway stated:

As for that man Gowrie, let none think that by this traitorous fact of his, our religion has received any blot, for one of our religion he was not, but a deep dissembling hypocrite, a profane Atheist, and an incarnate devil in an angel’s coat, as is evident both by his traitorous fact, which he attempted, and by the things which we have learned from his familiars, and most near and intimate friends.

The books which he used, plainly prove, that he was a studier of magic, and conjurer with devils, and had them some way at his command. [22]

In a sermon preached at the Mercat Cross in Glasgow, on 31s August 1600, Galloway stated:

The Earl studied necromancy when at Padua: that he had magical characters upon him when he was slain, and they who saw it testified that he could not bleed, so long as these characters were upon him. [23]

One is reminded of the fact that these are the same charges levelled against the Earl’s ‘divine theologian’ contact at Padua. It is also a charge which was levelled at protestant reformer John Knox, amongst others.

In pushing this agenda, Galloway spoke to the Earl’s private tutor, William Rhind, who confirmed that while they were in Padua together, the Earl carried around the papers which had been found in his possession on his death.

Galloway reported on this conversation, and Rhind was further examined under torture. Rhind added that he disliked these papers, and tried to destroy them on a number of occasions- evidently without success.

It seems the Earl came into possession of the papers when Rhind left him for a short period to travel to Venice. He saw the papers were marked with Latin and Hebrew characters, and when he remonstrated with the Earl about them, the Earl reportedly responded: “Let them alone, for they can do you no harm.”

Rhind asked where the Earl received the letters, and he replied that he had copied them himself. Rhind was satisfied the Latin characters were in the Earl’s own hand, but thought the Hebrew characters were written by someone else.

This suggests the Earl may have obtained them from someone else at Padua. Rhind insisted he had no reason to suspect the Earl of Sorcery.

News of the find travelled far. Sir Robert Cecil in England received word of it from one of his agents by the name of Nicholson in Edinburgh. Nicholson wrote Cecil on 14th August, 1600:

They say that upon the Earl of Gowrie were found characters, some for love, blood, &c. and one of them, the last, ‘contra potestatem divinae majestatis,’ viz. against the power of sacred majesty. [24]

A deposition was also taken from the Earl’s cousin, James Wemyss of Bogie, at Falkland Palace, on 9 August 1600.

He was asked if he ever had a conversation with the Earl “about things curious.” He related that in July 1600, he had accompanied the Earl deer-hunting on his country estate at Trochry, near Dunkeld in Perthshire.

Some of their party had slain an adder, whereupon the Earl allegedly said to him:

“Bogie, if they had not slain it, I would have shewed you a good sport, for I would have made it stand, so that it could not have passed away.”

Wemyss asked how he could have achieved this and the Earl replied:

“I could have done it by a Hebrew word, which in the Scottish language, means ‘Holiness’, and I have done the same sometimes before.”

Wemyss asked the Earl where he had obtained this “Hebrew” word, and the Earl informed him he had acquired it in a “cabbalist” of the Jews, and that this cabbalist (Cabbala) consisted of words that God spoke to Adam in paradise.

He emphasized that these words had far greater effect than any subsequently utilized by any prophet or apostle.

However, the Earl cautioned that these words had to be articulated with a firm faith in God, and that they were: “natural, and not matters of marvel, amongst scholars.”

It was here that the Earl further explained that “he had spoken with a man in Italy who was reputed a necromancer, but he was afterwards informed that he was a very learned man, and a deep theologist.”

The Earl had also related to Wemyss a story of how he had been at a social event when a man had looked him in the face and “spoke things of him,” of which he was not worth and could not aspire to.

The Earl asked this man to refrain from doing so, but the man continued to do so. The Earl said to him:

“My friend, if you will not hold your peace from speaking lies of me, I will make you hold your peace by speaking truth of you.”

He then advised the man that within a certain space of time he would be hanged for a crime, and this in fact did come to pass.

Wemyss asked the Earl how he possibly knew this, and he replied: “I spoke it by guess and it fell out so.”

One is immediately reminded of the gift of second sight, reported to have been held by the Brethren of the Rosie Cross in Scotland.

Wemyss counselled the Earl against repeating these things elsewhere, and the Earl assured him he would only speak of such things to great scholars, as any lesser person might misconstrue them as black arts. [25]

Contemporary English historian Sir William Sanderson (1586-1676), a firm supporter of the King, in his history of King James and his mother; Mary, Queen of Scots, published in 1656, was in little doubt about what the Earl had in his possession:

After thanks to God for this mercy, they surveyed Gowrie’s body, which did not bleed, until a parchment was taken out of his bosom, with characters, and these letters, which put together made TETRAGRAMMATON, having been told his blood should not spill, whilst he had that spell.

Being thus deceived by the devil, he thought he could not die, until he had power and rule, which he had of the King, and so suffered by the sword. [26]

The Rev. James Scott in his treatment of the Gowrie House mystery states:

The word ‘Tetragrammaton’, is Greek, and means, in that language, four letters. I am informed by dictionaries, that it was applied to indicate the scared name ‘Jehovah’, which consists of four letters in the Hebrew.

It was supposed that this word, when pronounced with faith, was accompanied with a powerful efficacy, and therefore was used as a charm or amulet.

If each letter was written separately in the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew characters, they would appear mysterious to them who had not learned how to arrange them. [27]

Sanderson appeared to suggest that the Earl’s possession of the word could gain him some advantage in overthrowing the King.

As an intimate of the Court, this gives us an insight into the thought processes of the King and his cohort at the time.

If Sanderson is correct, and given the known suspicious, and superstitious nature of the King, there can be no argument, that James saw the Earl’s possession of such knowledge, as a positive threat to his political and monarchical aspirations.

This would account for the King’s desire to attend in Perth as soon as possible on that fateful day.

Royal Arch historian Bernard E. Jones describes how the ancient Hebrews used a number of words to describe the Deity: ‘Almighty’, ‘Eternal’ ‘Most High’.

The most important of these words however, was the ‘Ineffable Name’ consisting of four words and known as the Tetragrammaton. (tetra, four: grammatos, letter). He writes:

The Tetragrammaton is an attempt to signify God in his immutable and eternal existence, the Being Who is self-existent and gives existence to others. It associates all three tenses- past, future, and present- and is the name to which allusion is made in 3 Exodus, 13-15. [28]

Jones also highlighted part of an 18th century Masonic ritual which asks how the Sacred Name should be depicted in our Lodges. The answer is:

By four different Hieroglyphics-

the first an equilateral triangle;

the second a circle:

the third a geometrical square;

the fourth a double cube. [29]

This is reminiscent of a passage in a work of Michael Maier. His book Atlanta Fugiens, first published in Latin at Oppenheim in 1617, is an alchemical emblem book containing fifty plates of mystical images, which Masonic scholar Arthur Edward Waite, stated “emblematically reveal the most unsearchable secrets of Nature.”

The text of emblem number twenty-one states:

Make of man and woman a circle; then a quadrangle; out of this a triangle; make again a circle; and you will have the Stone of the Wise. Thus, is made the stone which thou canst not discover unless you, through diligence, learn to understand this geometrical teaching. [30]

The Rev. Scott believed that when speaking to his cousin James Wemyss at Trochry, the Earl was simply trying to dazzle him with the knowledge he had acquired whilst abroad, and at the same time, highlight the futility of cabbalistic words.

However, as a Gowrie supporter, and a mainstream theologian, Rev. Scott may have had a vested interest in playing down any ‘magical’ aspects to this part of the incident.

Nonetheless, an interesting fact is that neither William Sanderson in 1656, or the Rev. James Scott, in 1818, appeared to have any real knowledge of the Tetragrammaton, Sanderson ascribed a demonic quality to it; albeit in an attempt to further besmirch the character of the Ruthvens, but it also seems that despite being an able theologian, Scott had to resort to dictionaries to obtain some understanding of it.

Suffice it to say, that the word, and its counterpart, are familiar to Royal Arch Masons. This point being made, there is no need for further comment.

On 30 October 1600, the dead bodies of John and Alexander Ruthven, which had been in the care of the magistrates at Perth, were taken to Edinburgh, where they were exhibited at their posthumous trial; which appears to have been common practice in matters related to alleged treason.

The Lord Advocate read out the various witness depositions, taken at Falkland and Edinburgh, and the brothers were duly convicted of Treason.

They were sentenced to be ‘hung, drawn, and quartered’, and their various body parts sent to the main population centres of Edinburgh, Perth, Dundee, and Stirling, as an example to those who would dare to plot against the King.

The Ruthvens were dispossessed of their lands and titles, and were ordered to change their surname.

Many of the family’s former lands were given to ‘gentlemen by the surname of Murray’. It will not go unobserved that the Moray/Murray family would be very prominent in Freemasonry both in Scotland and England in the years to come.

The Earl’s younger brothers, William and Patrick fled to England. William emigrated from Britain and subsequently became celebrated for his knowledge of Alchemy; and it was he who was reputed to have found the so-called Philosophers Stone.

On his ascension to the throne of England in 1603, King James had Patrick Ruthven arrested and committed to the Tower of London, where he spent almost twenty years.

Patrick, whose alchemical commonplace book was referred to earlier, is believed to have pursued his own interest in Alchemy and medicine whilst in the Tower, and may have had access to his own alchemical laboratory. [31]

CONCLUSION

Having secured sacred knowledge following the demise of the Earl of Gowrie, the King had to decide what to do with it.

The most likely scenario given his known esoteric interests, would be to form a group of like-minded men; members of his court, like his Master of Works, William Schaw, who shared his esoteric interests, and create a society in which this sacred knowledge could be preserved and practiced.

Given the likely source of this knowledge, namely Rosicrucian Germany, by way of Michael Maier in Padua Italy, they might have called their society: The Brethren of the Rosie Cross, if indeed that society was not already in existence in Scotland.

Given the reputed power and efficacy provided by this knowledge, those in possession of it would guard it jealously, and at the same time, be very wary of allegations of sorcery and witchcraft if their possession of such things were ever to leak out.

This would account for the need for oaths with severe penalties attached to them. It might also be the case that this knowledge was initially only shared by those intimately acquainted with the true nature of the incident at Gowrie House.

The Masonic historian, Bro. Rev. Francis de Paula Castells, was quite convinced that Freemasonry was cabbalistic in nature. He was equally convinced that the Royal Arch degree pre-dated the Craft degrees by some distance.

He based his belief on the fact that the ritual of the Royal Arch degree was replete with cabbalistic symbolism, and that the ancient brethren who framed the ritual had a thorough knowledge of the subject.

It was his belief that the cabbalists possessed a ritual or ceremony, which if not handed down directly to the Freemasons, certainly influenced later Freemasonry.

Part of his reasoning was the triad nature of cabbalism, including the cabbalistic tree of life, which contained a number of sephirothic triads, which is mirrored in both the Royal Arch degrees and the Craft degrees.

In the Craft, we have: the three degrees; the three Grand Masters; the three great lights; the three lesser lights; the three pillars; the three principle virtues.

There are similar such triads in the Royal Arch: the three Principals; the three sojourners; the three descents into the vault, and other examples.

Christians would later adopt and adapt the cabbala to their own purposes, and we are immediately reminded of the holy Christian trinity of: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Castells wrote:

The first reference of J.B.O. on record is in a metrical description of Perth, Scotland, The Muses by Henry Adamson, in 1638, where there occur two lines:

‘For we be brethren of the Rosie Cross,

We have the Mason Word and second sight’.The Poet evidently belonged to a new occult society called the “Rosie Cross,” the members of which were full of enthusiasm.

As a matter of fact, the Rosicrucians had made it a practice to seek initiation in the Masonic Fraternity, which we know was in existence in Scotland at the close of the sixteenth century, and some of them had gained the knowledge of the Sacred Word with all that that implies.

They also claimed some occult powers to which the modern Rosicrucians have no pretension. [32]

Elsewhere, Castells stated:

Spedding, in his Life of Bacon, brackets together ‘the fraternity of the Rosicrucians’, and the ‘lower Orders of Freemasonry’; or, in other words, the genuine illuminated Speculative Freemasons and the Craft Masons, who make their appearance from the middle of the seventeenth century. [33]

Quoting another author by the name of Mrs Pott, Castells continues:

Originally one and the same, alike in aims, alike in symbolic language, with similar traditions, tracing back to similar origins, some, at least, of the members supposed to have constituted the Rosicrucian Society actually were, we find, members of the Freemason’s Lodge.

Mrs Pott, although a woman, had a better insight into our history than thousands of present-day Masons. [34]

Castell’s further stated:

The great secret of the Rosicrucians, the ‘Mason Word’, is referred to in one of the Old Charges, the Chetwode-Crawley MS. of the seventeenth century, as ‘the Royal Secret’. It deserved to be called Royal, because both Freemasons and Rosicrucians traced it to ‘the Royal Solomon’.” [35]

This is of course a reasonable interpretation, but it might well be that the so-called Royal Secret was just that; a royal secret surrounding the motives for what occurred at Gowrie House in Perth in 1600.

A secret shared- on pain of death, amongst the King and his closest confidantes.

Quoting Adamson once again, Castells avers that the Mason Word, being the most convincing proof of a man being a Freemason, also appears to have been a characteristic feature of a Rosicrucian.

Castells also postulated that a sort of cabbalistic proto-Royal Arch degree was being worked long before speculative Freemasonry came into existence.

He claims that a stand-alone ‘Order of the Holy Royal Arch’ became a component part of the Master Mason degree, and at some point, the ‘Royal Arch’ element was disconnected from it, eventually becoming an autonomous Order. [36]

The present writer propounds that the opposite may in fact be the case; that elements of an existing ‘Holy Royal Arch Order’ may have been utilized in forming the Master Mason degree.

Indeed, if Castells is serious in his claims for the antiquity of the Royal Arch degree, this theory becomes unassailable.

It might also provide an answer to the question which has vexed Masonic scholars for decades, as to where the Master Mason degree originated.

It is known that the operative stonemason lodges practiced only two degrees: that of entered apprentice, and fellow of craft; and extant manuscripts show them to have been very short ceremonies.

We must also consider that the so-called father of Freemasonry, William Schaw, the author of the first and second Schaw Statutes of 1898 and 1899 (which some contend were formulated retrospectively), and King James VI’s Master of Works, was, like the King himself, extremely interested in esoteric matters.

In addition to the Art of Memory, both were interested in the Vitruvian principles of architecture, which contain the Vitruvian Triad, consisting of: Firmitas (strength), Utilitas (usefulness), and Venustas (beauty).

These principles were also applied to the human form, and were characteristic of cabbalistic, and hermetic principles.

These terms also found their way into the lexicon of speculative Freemasonry.

It is most interesting to note that the incident at Gowrie House in Perth, took place shortly after the second Schaw Statutes, which were reputedly issued in 1599.

Although the First Schaw Statutes appear to have been an attempt to reorganize the Mason Craft in Scotland, the second Schaw Statutes are more esoteric in nature, and make reference to The Art of Memory.

With the rise and pre-eminence of the Guilds and Incorporations, the need for separate operative Masonic Lodges would decline; and with this is mind, King James Vi and William Schaw, may well have decided to populate the former operative lodges with Brethren of the Rosie Cross.

This complementary admixture of operative masonic traditions and secrets, with those of the cabbalistic Rosicrucians, effectively transitioned these Lodges from operative to speculative concerns, and through time, the once separate groups coalesced into the Freemasons of today.

In other words, the Genesis of modern Speculative Freemasonry.

Castells’ theory that the Royal Arch degree was ever the sublime degree, that when formed, the three speculative Craft degrees were intended as being preparatory, and probationary, to the Royal Arch degree; a degree reserved for ‘Masters passed the chair’ seems eminently sensible.

The latter requirement has long since been abandoned, and yet the Royal Arch degree has retained its position as the ‘sublime’ degree.

Castells also claimed that: “The Rosy Cross had been at work in England from at least 1603.” [37]

He is clearly referring here to an earlier proto-Royal Arch degree, based on cabbalistic principles; and largely predicates this theory on the fact that on 6 January 1604, Anne, Queen consort to King James VI/I, held a Masque Ball at Whitehall, London, and asked famous architect Inigo Jones to design costumes to be worn by gentlemen attendees.

At the top of one design, in his own handwriting, Jones wrote “A Rosicros.” Castells cites this as evidence that certain gentlemen were members of an “Order of the Rosy Cross” as late as December 1603. [38]

Whilst interesting and suggestive, the facts of the matter are hardly authoritative or conclusive.

Notwithstanding, Castells receives support in these claims from present-day scholar Christopher McIntosh; a noted historian on Rosicrucianism, who in referring to an early Christmas card sent by Michael Maier to King James in 1612, states:

This was sent in the year of the very first recorded manuscript of the ‘Fama’, two years before it appeared in print as the first of the manifestos.

Yet here is Maier in 1612 addressing King James in terms that suggest the existence of a Rosicrucian-type movement in Britain, of which James was apparently seen as protector.

Although James was a violent opponent of witchcraft, he was probably not unsympathetic to the hermetic tradition and certainly had friends who were alchemists.

It is not impossible, therefore, that a Rosicrucian-type circle, interested in alchemy and Hermetic ideas and looking toward James as its patron, existed in Britain in the very early stages of the movement. [39]

It would seem therefore, that Maier’s connection with Scotland did not end following the demise of the Ruthven family, but indeed continued on apace.

Castells’ theses attract criticism today, as they did when he first published them. In 1931, a local Perth newspaper: The Courier and Advertiser, took issue with him (and other writers) concerning his conflation of the Brethren of the Rosie Cross, Mason Word, and second sight:

But he (Adamson) did not say, as these people would have us believe, that every brother of the rosy cross had the Mason word, any more than he said that every brother of the rosy cross had the gift of second sight. [40]

The columnist suggests that had Castells read the entire poem, and not simply cherry-picked certain passages, he would have avoided his error.

In this respect, the commentator was surely making an assumption as large as any by Castells. The piece concludes with the contributor appearing to tow the established party-line:

The purpose of his book is to show that there was a learned secret society in the seventeenth century, out of which modern Freemasonry has grown.

His enthusiasm for his particular view is undoubted, but critical students will see many flaws in his arguments, and it is safe to say he will not convince those who believe that Freemasonry derives from the ancient operative craft and the building guilds. [41]

Another interesting sidelight to this theory, is contained in a piece written by a respected 19th century Scottish Freemason: Anthony Oneal Haye, who was also a noted author and poet.

Prior to his initiation into Freemasonry in 1859, he was initiated into a Rosicrucian Society which was headquartered in his hometown of Edinburgh.

The origins of this particular society are shrouded in mystery. Haye rose to become head of the society and was styled Magus Maximus. This was a non-Masonic society which had a number of Freemasons as members.

Hayes’ society admitted a number of English Freemasons into its ranks, and subsequently granted a charter for these brethren to operate a Rosicrucian society in their own country.

This English society went their own way eventually, and its membership became exclusively Masonic, and adopted a Trinitarian Christian aspect.

Following the demise of Hayes’ society, the English society chartered a Scottish Masonic Rosicrucian society.

On writing about his society in the Masonic press of the day, Haye stated:

“The Rosicrucian society must not be confounded with its German bastard of the 17th century, which had its exponent in the ludicrous ‘Fama’, and gave birth to the present Royal Arch degree.”

He concluded:

My principal object, however, in writing this note, is to disabuse the minds of the brethren that there is any connection between the Rosicrucian Society and Freemasonry; and if any body of men calling themselves Rosicrucian maintain the existence of such a connection, they must be descendants of the bastard aforesaid. [42]

Haye was undoubtedly very informed on the subjects of Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism, and we have to take seriously his assertion of a connection between the Royal Arch degree, and the Rosicrucians of early 17th century Germany.

This immediately reminds us of the likely connection between the alchemists John Ruthven and Michael Maier.

Professor David Stevenson, author of a seminal work on the origins of Freemasonry stated:

The development of the Old Charges in England may be regarded as comprising the pre-history of freemasonry, essential to its later creation but not at the time part of anything that can meaningfully be called freemasonry.