Courage as a core value in Freemasonry

Brendan Hickey, PhD, PM, 32º, HGA, Master Masonic Scholar

We’re in this historic, dignified place, in the shadow of William Penn, so let’s start with this quote from him.

![]()

Right is right even if everyone is against it

And wrong is wrong even if everyone is for it

Since we’re going to talk a fair bit about honesty today, I want to model that value. The next slide is probably closer to my take on some of what we’re going to cover today.

![]()

Courage is knowing it might hurt and doing it anyway.

Stupidity is the same. That’s why life is hard.

— Jeremy Goldberg

What is Freemasonry? What’s our standard answer?

(A fraternity that makes good men better)

Sometimes we give a longer answer. What’s that?

(A system of moral instruction veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols)

For the brothers who are members of the Scottish Rite, Northern Masonic Jurisdiction, there are six core values. Can we name them?

(Devotion to Country, Integrity, Justice, Reverence for God, Service to Humanity, Toleration)

I’m a member of Thomson Lodge in Paoli. Above the station of the Worshipful Master in the East are the words “Faith-Hope-Charity.”

These are the three Theological Virtues, found in the Bible. Freemasons also talk about being honest and forthright, and practicing moderation. We’re not a service fraternity but we are rightly proud of our charitable efforts. That’s just what happens when good men get together.

As soon as we start to talk about Freemasonry, we talk about being a good man and we talk about virtues and values and ethics. There may be distinctions between those terms but I will probably use them interchangeably.

Today we’re going to talk about a value that we haven’t mentioned yet, and that’s odd, because I’m going to suggest that courage is the foundational value of Freemasonry, that it is not possible to be a good person without courage, or even to practice any other value without courage.

I don’t expect you to take my word for it. I don’t even want you to take my word for it. The need for a good person to have courage has been shared by a wide range of great minds across history, and today I plan to show you why.

Plato called courage “a very noble quality” and “a sort of endurance of the soul.” He called it one of the four cardinal virtues, along with justice, wisdom, and moderation. He distinguished thoughtful courage, which he regarded as rare, from rash and bold and fearless courage, which he regarded as common. Plato never defined courage, but he convinced Aristotle that courage was a virtue.

Immanuel Kant spent some time studying Aristotle’s thoughts on courage as a virtue. From Kant, we get a great quote, Sapere Aude (Sa-PERRY Ow-DAY) – “Dare to know,” or “Have the courage to know.” Loosely translated, it’s often stated as “Have the courage to use your own understanding.” That’s something that is expected of Freemasons, that we consider what we hear and then make our own judgements about what is true and worth following.

Fast forward to the 20th century and the well-known Serenity Prayer, attributed to Reinhold Niebuhr. Do we know this?

(The courage to change the things I can.)

If Freemasons are good men who are getting better, that requires change, and change is scary and painful and hard. We’ll talk more about that in a bit.

One more author. Maya Angelou said;

“Courage is the most important of all the virtues, because without courage you can’t practice any other virtue consistently. You can practice any virtue erratically, but nothing consistently without courage.”

Lots of different authors, different times and cultures, saying the same thing about courage.

Before we go any further, we need a definition of courage. What is it?

(Lots of references to fear)

For normal conversation, that works. People know what we mean. Most of the time, we know courage when we see it. The references to fear cause us two problems, though.

The first is that we all know stories about incredible courage, from veterans and first responders, people who did things like charge into burning buildings or enemy guns. When there’s an interview later, what does the interviewer always ask?

(Weren’t you scared?)

And what’s the answer every time?

There wasn’t time to be scared. I saw what was happening. I understood it. I remembered my training. I knew what I had to do, and I did it. Maybe there’s fear later, but not at the time, so if we need fear to have courage then we have a problem, because these are events of incredible, undeniable courage.

The second problem is specific to Freemasonry. In our degrees, a candidate is placed in a circumstance, or shown something, given some information, with the expectation that the degree will teach him something and lead to inner change. I’m not aware of a degree in which a candidate is asked if he is afraid, and I don’t think that Freemasonry would be successful if we were asking MEN about their feelings. Can you imagine that?

Yeah, I went to join the Masons, and they put me in a dark room and started to ask me about my feelings. I’ll tell you what, I ran out of that room and never looked back.

Fortunately, there are people who research courage. I have brothers who think that I’m an academic weenie and that’s OK. Here is where the research helps us out. Most modern definitions of courage say nothing at all about fear.

Instead, courage is an INTENTIONAL ACT. I’ll say that again. Courage is an intentional ACT. That fits perfectly for us as Masons, because we describe our fraternity and what we do in terms of WORK. There are lots of different types of courage, but we will limit this presentation to 4 types that make the most sense in terms of Freemasonry and what most of us do.

Those 4 types are physical, social, moral, and a really neat idea called workplace courage. They are different, but they often overlap, and they usually include an element of uncertainty about the outcome of the courageous act. One act can also be multiple types of courage.

Today’s presentation is open, which means that it’s being shared with people who aren’t Masons, so there are some things that I can’t say about our degrees. Those things aren’t secret, they’re private, and I promised that I wouldn’t share them outside of the fraternity, but I will do my best to be clear.

Physical Courage

This is the kind of courage that we just talked about. It’s clear and it’s easy to understand. Physical courage is when a person knowingly places themselves in physical danger to prevent harm to someone else or for a worthwhile cause.

We see it in many service jobs, military and first responders and construction workers – high steel, road construction – sanitation and health care. Every time that there is a school shooting, there’s a silent mass expression of physical courage by the teachers and students who return to work.

Coming back to Freemasonry, we know that there are times when being a good man means putting yourself into physical danger. Any time that you think about protecting someone, walking someone to their car, something along those lines, that’s what you’re saying. You’re putting yourself between danger and someone else.

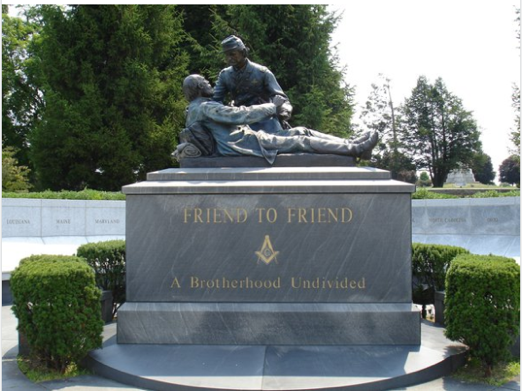

Thinking about some of our degrees, there is one that is a favorite here in Pennsylvania, an event that actually happened during the Battle of Gettysburg (picture of statue). Confederate General Lewis Armistead and Union General Winfield Scott Hancock were Masons and they were friends before the Civil War, and when Armistead fell during Pickett’s Charge, he was helped by Union Captain Henry Bingham, who was also a Mason. Bingham tended to Armistead and honored his Masonic promises and carried Armistead’s personal effects to Hancock.

There is also a degree that is set against the backdrop of the Oregon Trail, and one of the characters has cholera. Cholera is a deadly and infectious disease, and the Oregon Trail was a dangerous place. It’s this nation’s longest graveyard.

Over a 25 year span, up to 65,000 deaths occurred along the western trails. If they were evenly spaced along the length of the Oregon Trail, there would be a grave every 50 yards from Missouri to Oregon City.

In the Scottish Rite, the Civil War degree exemplifies Integrity and Devotion to Country, and the Oregon Trail degree exemplifies Integrity and Reverence for God. In our discussion today, both of these degrees exemplify physical courage and a few other types of courage that we will discuss in a bit. Let’s take a moment to talk about Integrity, though. It is dangerous.

Integrity is dangerous for two reasons. The first is that when you make a promise, you might find yourself later obligated to do something that you didn’t expect when you made the promise, maybe something that you don’t want to do, maybe something that is more or more difficult than what you had in mind.

Sometimes being a Freemason means hearing malicious lies about your fraternity. Many of these lies are about how Freemasonry is a secret society and about the promises that we make to each other. Many brothers have a standard reply, about “Freemasonry isn’t a secret society. It’s a society with secrets.” I have a bit of a different take on it, and it connects to the second danger of Integrity.

Freemasonry doesn’t really have many secrets left. Most of them have been published in books and online. It’s not hard to find what you want to know without joining the fraternity, but we still expect our members to promise to keep some information private. Those promises are about Integrity.

Are you really what you claim to be?

Will you really do what you promised to do?

Is your word good?

If the answers are yes then you are honest and you stand by your principles, which is to say, you have Integrity, and that’s dangerous because it makes you predictable. For anyone without integrity, your honesty makes you look weak, makes you look like a sucker. Integrity is dangerous and acting with Integrity is an act of courage.

Before we move on from physical courage, let’s think about some other degrees, and again, having to be careful about how I say this, there are times when a candidate is placed in unfamiliar circumstances, among unfamiliar people, often when he is not in a condition to protect himself or escape quickly.

Freemasons don’t haze and we don’t hurt candidates, but this is a new experience and he may not believe that. He does not know exactly what will happen to him. It would be understandable for a candidate to think that he is in danger. It takes physical courage to even become a Mason.

Physical courage is usually easy to spot and easy to see how it’s necessary for the practice of other virtues. It’s also easy to see how physical courage could be necessary for the practice of other types of courage, like moral and social courage.

Moral Courage and Social Courage

![]()

Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak

Courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen

— Winston Churchill

We’re going to talk about moral courage and social courage next. An intentional act can definitely be one or the other but these two seem to combine often, and I think that this is where most of us spend most of our time.

Moral courage can take the form of doing what is good for others, regardless of the risk to self, or it can mean standing up for a value, even against pressure, even if there is a risk of exclusion from your group.

That’s where moral courage overlaps with social courage, which is an action for a worthy objective that happens in a context of social intimidation, despite the need for some degree of connection to a group.

We are living in an extremely polarized era. We’re all on one side or the other and we’re not being given the same information, there’s an algorithm that makes money for someone else by telling us what we want to hear.

We assume that everyone hears the same things that we hear, and just to be sure, we get that extra nudge, that the other side, whichever it is, must be stupid and crazy and evil because they don’t have the same opinion about what we mistakenly assume to be the same information. We’re broken into tribes and we think that the other side is dangerous. Safety is with our own tribe.

Humans are social animals, and it goes beyond being liked, which is important enough. Down to a certain level of weakness, the pack will rally around a member, trying to protect them and strengthen them, but as soon as the weakness gets to be too great, the member is a threat to the pack and the switch flips and the pack turns on the member, who becomes the enemy.

You might think that this happens in street gangs. I don’t know, maybe it does, but I know that it happens in many places, even in monastic communities. To be safe, we need to belong.

![]()

Always stand up for what is right.

Even if it means standing alone

Let’s take this combination of moral and social courage one step further. We can say that we admire the person who stands up for his values, and sure, at the extreme, this readily combines with physical courage to become the stuff of heroes and martyrs, but what happens when you stand up and say that you need to do what you think is right, and that right that you are doing is different from your pack? How does that sound to your pack?

You’re telling them that what they are doing is wrong and you’re right, but we all believe and need to believe that we are right. We’ll admire the man who stands up for what he thinks is right until it’s something different from what we’re doing.

I suggest to you that Freemasonry is our pack. Among our expectations is that we will be benevolent and moral toward everyone, including and especially people who don’t agree with us, because it’s easy to be benevolent and moral to your friends.

To step out of the group-think and reach across the barbed wire and see the Other as a person, the same as yourself, deserving of the same respect and kindness as yourself, is a dangerous act. It is an act of moral courage and it is an act of social courage.

It is the act of a Freemason. Freemasonry is our pack and it has existed since time immemorial, long before a political party or social movement or social media platform. Freemasonry will outlast all of those, too.

Thinking about the Gettysburg event degree, there was physical courage in stopping during a battle to help an enemy, at least to a person dressed as an enemy, but there was also moral courage.

Captain Bingham followed a set of distinctly Masonic expectations while interacting with General Armistead. Captain Bingham’s actions were also social courage. He risked the respect of other Union soldiers, the belonging that he absolutely needed in combat, by being kind to a man who they regarded as their enemy.

Let’s go a step further and think about the social courage that it takes to even become a Mason. What are the malicious lies that are told about us? We hear that we worship Lucifer and we hear that we worship Baphomet and we hear that we are Illuminati who control the world.

There are churches that don’t want their members to become Freemasons, churches that will even expel us for joining. We can lose friends and family members who believe these lies.

Every time that someone notices your ring and says, “Oh, you’re a Mason,” there’s a chance that the next part will be about how Masons are good men and that they know someone who is a Mason, and there’s a chance that you’re going to be falsely accused of something ridiculous and awful. We take that on when we join Freemasonry.

I think that moral courage and social courage are the stuff of everyday life. They make possible the routine practice of being a person. Let’s look at the Scottish rite value of Toleration, which means respect for the opinions of others.

You don’t have to agree, but you should respect those opinions in the same way that you want your opinions respected, and you can’t do that without listening to someone who is different from you and maybe hearing something that you not only don’t agree with, but that really upsets you. That’s a risk.

There’s also a risk in standing up to defend someone else, and here again is the combination of moral and social courage. We’re men, and that means that we have a lot of power.

The moral use of that power is to defend people who don’t have power, people who are being bullied and beaten down. That’s the Scottish Rite value of Justice. That’s moral and the act of a Freemason and it takes courage.

Workplace Courage

![]()

If it excites you and scares you at the same time,

it might be a good thing to try

We have one more type of courage to talk about, one that may be new to you. It was new to me when I started to look at this topic. We’re going to talk about workplace courage, which seems to be perfectly suited to Freemasonry, and then we will wrap up by talking about what we can do with all of this information.

Workplace courage is defined overall as a work domain-relevant act done for a worthy cause despite significant risks perceivable in the moment to the actor. Yeah, there’s the academic weenie stuff, but this is going to be good, I promise. There are a whole bunch of types of workplace courage, but for Freemasonry, four types stand out:

1. Positive or constructive deviance – intentional behavior that departs from the norms of a referent group in honorable ways.

2. Prosocial rule breaking – intentional violation of formal policy, regulation, or prohibition with the primary intention of promoting the welfare of the organization or one of its stakeholders.

3. Improvement-oriented voice – verbal behavior that constructively challenges the status quo with the intent to improve rather than merely criticize a situation.

4. Proactive behavior – anticipatory employee action taken to impact oneself and/or their environment.

That’s a mouthful, and it’s jargon, and it’s probably new information, so let’s break this down. There are two groups here. The first group is about challenging the norms and the second group is about making improvements.

In the first group, positive or constructive deviance is when you follow your own values even though it means separating from your group. Prosocial rule breaking takes that a step further. It happens when you knowingly break the rules of an organization to benefit the organization or someone who is important to it. We see this one in movies all of the time.

Most recently, it’s Maverick in ‘Top Gun’. It’s a fun idea, breaking the rules and getting away with it and even making things better, but that mostly happens in the movies. Organizations take care of themselves, and though others may admire your courage and what you did, they’ll leave you to your own devices. Again, there’s overlap with moral courage and social courage.

Coming back to the Scottish Rite degrees, there is another one set against a historical event, the sinking of the SS Dorchester, a troop ship that was torpedoed and sunk during World War 2, in February 1943.

There were four Army chaplains on board, from various religions and denominations. While the ship was sinking, these men remained aboard and prayed, and they gave their life jackets and warm clothing to other men.

It’s a true story and you can look it up. In the Scottish Rite, this event exemplifies Reverence for God, Toleration, Service to Others, and Devotion to Country. In our discussion today, this event also exemplifies physical courage, moral courage, prosocial rule breaking, and proactive behavior, working to improve yourself or your environment.

Proactive behavior and the improvement-oriented voice are about trying to make a situation better. It’s not the keyboard commando who slams everything from afar. It’s the man in the arena, the guy with sweat on his face and skin in the game, working to pull the organization and colleagues up.

Freemasons are expected to correct our brothers gently, and this is a value that shocks people who think that we support each other unconditionally no matter what we do. Freemasons don’t work like that. This type of workplace courage happens when you work to improve yourself or your environment. This is about the hard and scary journey of becoming better.

![]()

If you could kick the person in the pants responsible for most of your trouble

You would not sit for a month

–Theodore Roosevelt

Becoming better is tough and dangerous work. It means seeing that how you did things wasn’t the best way, so now you need to do better. That takes honesty and responsibility.

Honesty? We all think that we want it, but we don’t.

Does this dress make me look fat?

Do I look stupid to you?

If I vote for you, what will you do for me?

How are you today?

That’s honesty with other people. If you really want honesty, work with kids. I want to lose some weight this summer because the students keep asking me if I’m having twins. I bring this up because I’m using a calorie tracker, and there are times when I’m really tempted to lie, as though that makes any sense.

Honesty with yourself is even harder than honesty with other people. You can’t even lie and pretend to believe the lie that you told yourself. That’s why it goes hand in hand with responsibility, seeing the wrong that you do and the good that you fail to do and knowing, in that painful moment, that you have to do better. It’s a lot easier to just believe that you’re right.

Fortunately, if you reach that painful moment, seeing that you are doing something wrong, the next moment is the relief of knowing that this means that you have the power to change your situation. Masons are expected to improve ourselves and to gently correct each other, but it’s a lot safer to just ignore it.

![]()

Courage, hard work, self-mastery, and intelligent effort

are all essential to a successful life

–Theodore Roosevelt

As we start to wrap up, let’s take another look at those values that we mentioned at the start. Faith, Hope, and Charity, the Three Theological Virtues. Faith is the belief that a God you can’t understand and can’t prove exists will provide for and protect you. That takes courage. Hope is the same thing except talking about the future, that it will be good, and that takes courage.

What about charity? You might not see a risk. You bought some new socks and gave them to Joy of Sox in Phoenixville so they can give them to homeless people, or you spent the day entertaining sick children at a Shriner’s Hospital, or you drove out to a Masonic Village to serve our retired brothers and their wives, no big deal.

What you did, though, was you took your money, and your time and energy, that you could use to make money and to take care of yourself, and you gave it away. You can’t get it back. You’ll probably be OK, everything will probably be the same at home when you return, but you can’t be sure. You took a risk for something that you thought was worthwhile, and that act is courage.

We talked about the Scottish Rite values of Integrity and Justice and Toleration and we mostly covered the values of Service to Others and Reverence for God and Devotion to Country. There’s always more that we can say but there are limits to time and attention and we need to talk about what we’re going to do with this stuff.

Application

![]()

You’ve got enemies?

Good, that means you stood up for something in your life

Freemasonry is all about useful knowledge, so now that we have some new information, what are we going to do with it? I have three suggestions:

The first is that we realize that we have taken sides in the battle between good and evil. The square and compass is a symbol of that decision and as real as a badge or uniform. We’re not neutral. We have declared ourselves to be good men, who are becoming better, and that comes with risks and sometimes it even comes with enemies.

The second suggestion is that we need to realize, and teach, that the work of Freemasonry is hard. I know a martial arts instructor who teaches kids that discomfort leads to movement and growth. Kids. We’re grown men. We should know that growing is hard, that being a good man in a world that is often bad, is hard. Rocky Balboa said, “It’s not about how hard you can hit, it’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward. That’s how winning is done.”

We talked about academic weenies, knowing the right answers without having to live the challenges, so keeping with the boxing metaphor for another moment, what do they say, that everyone has a plan until they get hit? It’s easy when you don’t have to do it. It’s easy when you don’t understand it. Freemasonry is all about knowing and doing.

At the same time, though, we can see how gentle we need to be, with others, with ourselves. What looks like a moral failure may actually be a failure of nerves. Knowing what is right takes understanding. Doing what is right takes courage, and that’s a different set of skills.

My third suggestion is that we teach courage. Fortunately, that’s possible. Sure, some people are naturally brave, but again, courage is an act, and so it is possible to learn how to do courage. Even better, Freemasonry is all about teaching and learning.

I don’t know all of the degrees in Freemasonry. I know the Blue Lodge and Scottish Rite and Royal Arch degrees and a few others, and all of them require and exemplify at least one type of courage, usually a few types. We have stories set in the Old Testament and the American Revolution and lots of stories about knights and missions. I think that we’re showing courage all of the time.

Now that we know that we don’t have to admit to being scared to talk about courage, that we don’t have to talk about our feelings at all, it’s safe to talk about courage, so we can point out courage among the other values in our degrees.

![]()

Misneach (Mis-nock)

Courage, ability to push forward through uncertainty

–Irish word of the day

Awhile ago, I said that many moral failures are actually failures of nerve, failures of courage. That can happen when we haven’t experienced or considered a situation before, when we’re not sure what to do.

If you look at the training of emergency responders, much of it is about the “what-if” events. The wrong time to learn a new skill is in the middle of an emergency. Encouraging our candidates to imagine themselves in those situations and think about they might handle them, how they want to handle them, is a good way to prepare.

They can do this with others or they can do it, privately, on their own time. This is instruction based in story-telling, or allegory, which is what Freemasonry does.

There’s one more way. We learn courage by observing others, which is also part of how Freemasonry makes good men better, by learning from each other.

Specifically, I’m talking about leadership. Just like courage, there are people who are natural leaders, but those skills are better when they are taught and refined. Freemasonry has schools for leaders.

I was a Worshipful Master, and that was tough. The only way that I can imagine what it’s like for the District Deputy Grand Masters is to think of the trouble that I caused them. For the brothers who are further up the line, yeah, that’s a hard job.

Courageous leadership, setting a good example, isn’t a swagger or arrogance. That’s weakness. Instead, we’re looking for the guy who is honest and who says, “This will be hard, but whatever comes, we got it.”

The brothers at Palestine – Roxborough Lodge No. 135 recently posted something on their Instagram page that captures this attitude perfectly, so I’m going to let them have the last word.

[and I’m going to stop talking and catch my breath and then I will try to answer any questions.]

![]()

Be ok with not knowing for sure what might come next,

But know that, what ever it is, you will be ok

Embrace the journey of uncertainty, for within lies the beauty of growth. As Freemasons, we understand that life’s path is like walking up a winding stair.

While we may not know what lies beyond each turn, we trust in the teachings that guide us.

Have faith that whatever comes next, you possess the strength to overcome and flourish.

Let the winding stairs of life lead you to new horizons, knowing that you are equipped to navigate the unknown. Keep moving forward, for vou are capable and resilient.

Article by: Brendan Hickey

Brother Brendan M. Hickey, PhD, is a Past Master of Thomson Lodge No. 340 in Paoli, PA.

He is also a Hauts Grades Academic and a Master Masonic Scholar. Brother Hickey is a book reviewer for the Journal of the Masonic Society and an officer in the PA Lodge of Research.

He has been published in Philalethes: The Journal of Masonic Letters and Research. Brother Hickey works as a school psychologist.

Recent Articles: skills

7 Soft Skills Taught In Freemasonry Discover how Freemasonry nurtures seven irreplaceable soft skills—collaboration; Communication, Teamwork, Empathy, Flexibility, Conflict Resolution, Active Listening, and Trustworthiness. Explore how these essential human attributes, grounded in emotional intelligence and ethical judgment, remain beyond the reach of AI. |

Freemasonry and Reskilling in the age of AI The article explores the challenges and strategies organizations face in reskilling their workforce in the era of automation and artificial intelligence. It highlights the need for companies to view reskilling as a strategic imperative and involve leaders and managers in the process. The article also emphasizes the importance of change management, designing programs from the employee's perspective, and partnering with external entities. |

Ten Central Commandments or Principles of Freemasonry Embrace the wisdom of Freemasonry's teachings in your personal journey towards self-improvement and stronger leadership. By upholding virtues of integrity, compassion, and respect, and uniting these with a commitment to continuous learning and social responsibility, inspire change. Transform yourself and the world around you, fostering a legacy of positivity and enlightenment. |

Freemasonry: A Guide to Fatherhood In the sacred halls of Freemasonry, fathers discover a hidden power to transform their parenting journey. With its timeless values, supportive community, and life-enriching teachings, Freemasonry empowers fathers to provide a moral compass, foster self-improvement, build stronger connections, and embrace the confidence and wisdom needed to navigate the complex realm of fatherhood. |

Courage as a core value in Freemasonry Freemasonry, a revered fraternity, prioritizes virtues like honesty and charity. However, courage is foundational. From Plato to Maya Angelou, courage is vital for other virtues. Freemasonry's teachings, referencing events like Gettysburg, emphasize diverse courage forms. In today's divided world, Masons promote and exemplify courage, understanding its importance in facing challenges. |

How Freemasonry Cultivates Ideal Entrepreneurial Traits Freemasonry's cryptic rituals hold timeless lessons for building entrepreneurial greatness. Through tests of passion, vision and skill, Masonic teachings forge ideal traits like grit, creativity and alliance-making needed to seize opportunity and elevate enterprises. The right commitment unlocks code for entrepreneurial success. |

What you see praiseworthy in others "What you see praiseworthy in others, carefully imitate, and what in them may appear defective, you will in yourself amend". This passage of Masonic ritual (Taylors Working, Address to the w |

How to Learn Ritual with a Learning Disorder So what do you do when faced with that little blue book? Most Masons when first looking at the ritual book can understandably be fazed – the tiny print, the missing words, the questions and answers! Learning ritual can be a challenging task for anyone, especially individuals with learning disorders, but it is not impossible. Here are some tips to help make the process easier. |

A "mind palace", also known as a "memory palace", is a technique for memorizing and recalling information. How would your life change if you could remember anything and everything? Discover the 'Mind Palace' and all will be revealed. |

What is leadership and who does freemasonry help develop those skills needed to be a better leader |

A story of the 'Ruffians' – those individuals whose paths cross ours, who feel entitled to seize and consume the property of others that they have not earned. A lesson to build character to be a better citizen of the world. |

Now we are back in the Lodge room once again, maybe it is time to review how we learn and deliver ritual and look at different ways of improving that process. |

Making an advancement in Masonic Knowledge can become far easier when you 'learn how to learn'. |

Learn how to practise Masonic meditation in a busy world with all its care and employments |

Struggling to learn your ritual? Become a 5-Minute Ritualist with the aid of a book of the same name. |

Day in the life of a Freemason As we start a new year, maybe start it with a new habit? |

Ten Basic Rules For Better Living Ten Basic Rules For Better Living by Manly P Hall |

How can we use masonic leadership skills to avoid confrontational situations? |

How the Trivium is applied to Critical Thinking - {who, what, where, when} - {how} - {why} |

The Seven Liberal Arts - why 'seven', why 'liberal', why 'arts'? |

How to improve your public speaking skill with 6 techniques |

Do you need to speak in public, or present Masonic ritual without notes ? |

What are logical Fallacies and how to spot them |

Share one easy tip to learn masonic ritual; Some good tips from Facebook followers |

How can we use the 7 secrets of the greatest speakers in history |

What is a critical thinker and what are their characteristics? |

Share one personal skill Freemasonry helped you to improve? How can we make practical use of the lessons taught in Masonic writings? |

An introduction to the art of public speaking - speak with confidence |

Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences What do you know about Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences |

Three Words That Will Change Your Life This article discuss a common situation found in many lodges - a difficulty in holding a conversation with a stranger. |

Al - Khwarizmi live c750 - c820 is credited as being the father of Algebra, being asked what is Man, give his answer in an algebraic expression |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device