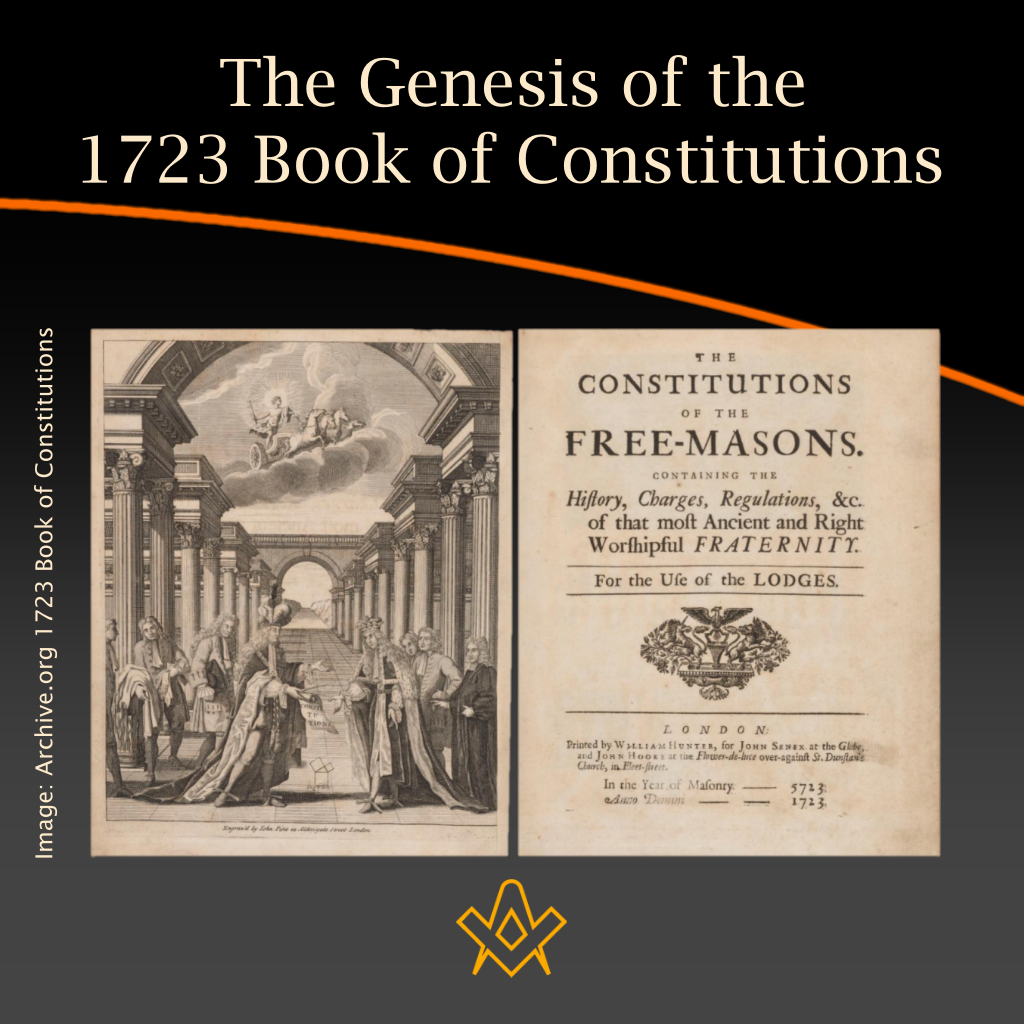

2023, marks the three hundredth anniversary of the publication of the first printed Book of Constitutions of the Grand Lodge formally established in London two years previously.

This is an anniversary whose significance extends beyond freemasonry.

The distinguished historian of eighteenth-century Britain, Dame Linda Colley, has recently suggested that the publication of constitutions by freemasons contributed to the political enthusiasm for written constitutions not only in the United States and France but also in smaller countries such as Corsica and Pitcairn in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

While the 1723 Constitutions are among the most celebrated masonic publications and the name of its author, James Anderson, is well known, there has been little discussion of the circumstances of the compilation and publication of the 1723 Constitutions.

The process of compiling and publishing the Book of Constitutions was highly contentious and led to one of the first public controversies involving the new Grand Lodge.

Much of the impetus behind the production of the Book of Constitutions came not from Grand Lodge or its officers, but rather from the booksellers and publishers, who saw the Book of Constitutions as their property.

The story of the production of the Book of Constitutions shows that the creation of the new Grand Lodge was by no means uncontroversial and there were key figures who objected to the political and social baggage of the new Grand Lodge.

ROBERTS ADVERT

The Book of Constitutions was produced at the Grand Lodge on 17 January 1723 and its publication was approved and the book recommended for the use of lodges.

One week later, an incendiary advertisement headed ‘For the benefit of the ancient Society of Freemasons’ appeared on the front page of the Daily Journal.

It began by noting that ‘there is now ready for Publication, a new Set of Constitutions and Orders, very different from the Ancient, by which the said Society has been happily, and quietly, regulated for many Ages past’.

The advertisement then launched a ferocious attack on the new constitutions and their author:

The extravagant Length of the said new Constitutions, and Orders, exceeding that of four ordinary Sermons, makes it most evident, that they are calculated at the Expence and Damage of the Society, meerly to serve the Interest of one single Member, the Author, whose assurance was such, that he got them printed off before he offers them to the General Censure of the Fraternity. For which Reasons, we hope, the Brotherhood will not now be over hasty to encourage the said Innovator;

The new constitutions were, the advertisement claimed, a scam and imposition on the brethren.

The existing constitutions were perfectly satisfactory and could be printed for a fraction of the price of 2s 6d charged for the new constitutions.

The advertisement promised all Lovers of pure Masonry, abstracted from Innovations, and Self-Interest, that there will speedily be prepar’d, and deliver’d to them, without Cost, The Ancient Constitutions, and Orders, taken from the best Copies; wherein such Errors in History, and Chronology, which, by the Carelessness of the several Transcribers, have crept into them, will be fully rectified.

This version of the constitutions would shortly be printed for the cost of 6d, instead of 2s 6d, and on as good a paper as the new constitutions.

The man responsible for attacking on Anderson’s Book of Constitutions before it even appeared was James Roberts, one of the most prolific trade publishers in London.

Roberts published a very wide range of books and pamphlets, ranging from work by Henry Fielding to more scurrilous anti-catholic pamphlets.

Roberts was rumoured to have been closely connected with Edmund Curll, the notorious publisher of pornographic books and butt of Alexander Pope’s scorn.

Roberts’s attack on the 1723 Constitutions was doubtless partly motivated by pique that he had missed out on a major commercial opportunity, but Roberts’s ire also reflects issues going back to the origins of the new Constitutions.

COOKE MANUSCRIPT

The masonic lodge associated with St Paul’s Cathedral, which is supposed to have met at the Goose and Gridiron, saw itself as the guardian of the traditions of the craft.

This is partly because it possessed some of the oldest and most elaborate copies of the Old Charges.

At the dinner in June 1721 at which the existing masonic lodges in London and Westminster agreed to place their authority in trust to a new Grand Lodge and the Duke of Montagu was elected as Grand Master, George Payne of the Horn Lodge in Westminster sensationally produced the Cooke manuscript of the Old Charges, which was demonstrably much older than the manuscripts held by the St Paul’s lodge.

As the possessor of a much older manuscript of the Old Charges, Payne and the Horn Lodge were able to challenge the claims of the St Paul’s Lodge to be the guardian of the ancient lights of masonry.

Moreover, the Cooke manuscript differed in substantial points from the other manuscripts of the Old Charges known to the London lodges.

The most urgent requirement posed by the discovery of the Cooke manuscript was to work out how far errors had entered into the history and chronology of the Old Charges.

The manuscripts needed to be reconciled and monkish error removed. This was the job that James Anderson, who was already working for the publishers of the new Constitutions, was commissioned to do.

But the idea of jettisoning the Old Charges and replacing them with a revised and up-to-date text was contentious from the start, and seems to have been a major focus of resistance to the new Grand Lodge.

ROBERTS OLD CHARGES

James Roberts took the most prominent role in resisting the compilation of the new Book of Constitutions.

Determined to demonstrate that the Old Charges could be retained, he reprinted the Old Charges in one of his journals, The Post Man, in July and August 1722.

The reprinting of the Old Charges was evidently intended to undermine the project to impose the new Constitutions.

In September 1722, Roberts took matters a stage further by publishing separately a version of the Old Charges which he claimed had been taken from a manuscript over 500 years old, suggesting that the text was of comparable authority to the Cooke manuscript.

Roberts’s publication also contained some ‘new articles’ said to have been promulgated in December 1663, which was also intended to undermine the argument that the Constitutions needed to brought up to date.

ADVERT AGAINST ROBERTS

In response to Roberts’s publication of the Old Charges, Grand Lodge hastily took out newspaper adverts to:

…to advise the Publick, that the same is false and spurious, nor does the said Book contain anything like the true Constitutions of the Society, but is calculated to deceive the Publick. Whereof we desire the Brotherhood to take notice.

The timing of the various approbations included in the 1723 Book of Constitutions show that the text took a long time to compile.

This was apparently not only due to Anderson not working as speedily as he might but also possibly the result of debates within Grand Lodge.

The grandiloquent language of the first approbation is doubtless the work of Anderson himself.

It states that the Duke of Montagu, having had the manuscript read and corrected by several brethren, ordered it to be printed, but that it was not ready for the press when Montagu stepped down as Grand Master.

It seems possible that sections were possibly printed in the summer of 1722, which may account for Roberts’s claim that the book had been printed without permission of Grand Lodge.

There was continued revision and addition to the book, including the addition of the songs and other supplementary material, until January 1723.

The delays proved sufficiently long that it was thought desirable to insert a second approbation in the names of Grand Master Wharton and his Deputy Desaguliers.

ROBERTS ADVERTISEMENT

On 11 February 1723, James Robert launched a preemptive strike against the new Constitutions by advertising his edition of the Old Charges at the promised price of 6d.

HUDIBRASTIC POEM

The following week, there appeared another hefty attack against the Grand Lodge with the publication of the bawdy Hudibrastic poem The Free-Masons which parodied the masons traditional history and accused lodges of indulging in such practices as sodomy and masturbation.

This lively piece of eighteenth-century erotica ran through three editions in a week. It was published under a false imprint, but there can be little doubt that James Roberts, who was active in the publication of erotic literature and well-versed in the use of false imprints, was responsible for the Hudibrastic poem.

Its appearance must have been particularly unsettling to James Anderson, because he had been the target of two similar obscene pamphlets in 1720.

Although Anderson is not directly referred to in the Hudibrastick Poem, the dedication is addressed to ‘one of the Wardens of the Society of Free-Masons’ who was said to have been a ‘mercenary scribbler’.

LONDON JOURNAL

It was under these circumstances that the London booksellers John Senex and John Hooke advertised the publication of the Book of Constitutions on 23 February 1723.

But the appearance of the Book of Constitutions seems to have added to the controversy rather than settling it.

On 6 April 1723, the London Journal reported that the Society of Free Masons had given orders to prosecute with the utmost severity a gentleman who had criticised the management of Grand Lodge in one of their meetings.

PRITCHARD

The following month, Henry Pritchard was tried for assault after breaking the head of one Abraham Barret for ‘abusing the ancient Society of Free Masons in a very scandalous Manner, and with very indecent Expressions, particularly relating to some noble Persons of that Fraternity mention’d by Name’.

The jury found against Pritchard but, because of the very great provocation, only awarded 20 shillings damages. Grand Lodge afterwards made a collection of £28 17s 6d so that Pritchard should not lose out from his defence of Freemasonry.

It seems to have been these clashes that prompted Grand Lodge to appoint a Secretary and start to keep minutes of its meetings in June 1723.

At this meeting, the very first vote called into question the validity of the approbation of the 1723 Constitutions – the minute refers to the order ‘purporting that they had been approved’.

When the meeting was asked to confirm the general regulations printed in the book so far as they were consistent with the ancient rules of masonry, it was decided that the question should be not put.

Instead, a pointed resolution was passed; ‘That it is not in the Power of any person, or Body of men, to make any Alteration, or Innovation in the Body of Masonry without the Consent first obtained of the Annual Grand Lodge’, the implication of this being that the Constitutions had effected such changes without proper consent.

Tempers remained frayed, and much of the opprobrium was directed at Desaguliers. In November, William Huddlestone, the Master of the lodge of the King’s Head in Ivy Lane was expelled from the Grand Lodge and removed from his Mastership for casting aspersions against Desaguliers.

ADVERTISEMENT

Anderson’s role in the writing of the new Book of Constitutions was evidently part, but not the whole reason, for the controversies surrounding its publication.

How was Anderson recruited? Anderson claimed that it was a personal commission to him from the Duke of Montagu.

He also claimed that he was at that time made a Warden of the Grand Lodge. However, Anderson personally forged Grand Lodge minutes to substantiate his claim to be a Warden and he probably was never made Warden.

In fact, it seems probable that Anderson was not even a mason at the time he was commissioned to revise the Constitutions.

The clue as to how Anderson came to be asked to work on the commissions is in the advertisements for the Book of Constitutions which appeared in February 1723.

At the same time as the Book of Constitutions was advertised, one of its publishers, John Hooke, was advertising Interviews in the Realms of Death, a translation of David Fassmann’s Dialogues of the Dead, a popular German series of dialogues between historical characters.

Hooke was joined in the publication of the Interviews by Richard Ford and John Graves and they used the same printer as the Book of Constitutions, William Hunter.

The engravings in the Interviews also seem very similar to the work of John Pine who engraved the frontispiece of the Book of Constitutions.

DIALOGUES OF DEAD

Anderson’s involvement in this project illustrates his knowledge and receptiveness to contemporary European Enlightenment thought.

Richard Ford had published sermons and other works by Anderson, and it was evidently Ford who introduced Anderson to the Book of Constitutions project.

Following the ways in which Anderson alters and develops Fassmann’s original text – including inserting a reference to the Grand Lodge of Freemasons being like the chivalric order of the Hospitallers – provides fascinating insights into his working methods.

Anderson and his publishers had great hopes for the Interviews in the Realms of Death. The aim was to publish in monthly installments translations of thirty-eight of Fassmann’s conversations.

Anderson stated that the conversations will form ‘not only the compendious History of former Times, but even a Continuation of the News and present State of Europe, beginning Anno 1718.’

However, we can see in the translation Anderson slowly tying himself up in knots with some of the political and religious implications of Fassmann’s text.

After translating three conversations, the project was first delayed and then dropped, in the translator’s words, ‘it being very laborious.’

SENEX & DESAGULIERS

The key team behind the production of the 1723 was taken from the Interviews in the Realm of Death: Hooke as publisher, Anderson as author, Hunter as printer and perhaps Pine as engraver.

Hooke was joined as publisher by John Senex, who is best known for his beautiful maps and globes and who was also a prolific scientific publisher.

Senex was involved in publishing many of the key scientific authors of the period including Hauksbee, Gravesande, Whiston and Newton.

Senex had a close working relationship with Desaguliers. Tickets for Desaguliers’s public lectures were sold at Senex’s shop and Senex published Desaguliers’s Course of Experimental Philosophy.

Senex’s name appears first on the title page, implying that he was the major partner in the production of the Constitutions.

His contribution was probably financial, supporting the production of a book with a longer print run and higher quality production than Hooke would have been able to manage on his own.

Senex also provided a link with Desaguliers who prominently contributed the dedication.

TITLE PAGE

All of which emphasises that the Book of Constitutions was primarily a project driven by Senex and Hooke as publishers, rather than Grand Lodge or Anderson.

This is made clear by the title page, where the imprint makes it clear that the publisher and owners of the copyright were Senex and Hooke.

After the death of Hooke in 1730, his business and all the copyrights owned by it were acquired by Richard Chandler, who was to be one of the publishers of the 1738 Constitutions.

Anderson was – as James Roberts hints – paid by the page as a ‘mercenary scribbler’ for his work on both Books of Constitutions. Grand Lodge had no claim over the contents of the Book of Constitutions beyond its approbation, but this was a valuable imprimatur

MS CONSTITUTIONS

The Book of Constitutions went through a long print run – probably as many as 5,000 copies were produced.

But with the growth of freemasonry, by the early 1730s, copies were beginning to become scarce.

This can be seen from a manuscript copy of the 1723 Constitutions in the Museum of Freemasonry in London which was produced for lodge use, and suggests it was by the early 1730s easier to copy out a copy of the Book of Constitutions than acquire a printed copy.

ANDERSON FLEET

Which brings us to Anderson’s celebrated complaint to Grand Lodge about the publication of William Smith’s Pocket Book in 1735.

Anderson was of course telling Grand Lodge fibs when he claimed that he owned the copyright of the Book of Constitutions and that Smith’s book infringed his rights.

Anderson had no such claim, but he was a man in desperate straits as in October 1734 he had been sent to the Fleet Prison as a bankrupt and he was trying desperately to clear his debts – and the eventual production of the 1738 Book of Constitutions was closely linked to the collapse of Anderson’s finances.

POCKET COMPANION ADVERTS

It is possible that Anderson not only exaggerated his own claim to the copyright of the Book of Constitutions, but he may also have exaggerated the competition from the Pocket Companions.

It is likely that the Pocket Companions were principally aimed at the Irish market. The first companion had a title page stating that it was published for Ebenezer Rider at Blackmore Street near Clare Market in London in 1735.

But by June 1735, Rider was printing a journal in Dublin and produced an Irish edition of the Pocket Companion.

It is therefore likely that this first Pocket Companion was in fact produced by Rider in Ireland an sold by a collaborator under a false title page in London.

If so, Rider’s partner was probably John Torbuck, who published a number of books in partnership with Rider. Torbuck’s close collaboration with Irish booksellers is evident from his imprisonment in 1739 for publishing debates in the House of Lords.

Torbuck had brought the transcripts of the debates from a Dublin bookseller. When he was released from Newgate, Torbuck went to Dublin where his partnership with Rider flourished and the short early history of the Pocket Companions came to an end.

About The Authors

Andrew Prescott is Professor of Digital Humanities in the School of Critical Studies at the University of Glasgow. He was Director of the Centre for Research at the University of Sheffield from 2000-2007. He has published many books and articles on medieval history, libraries, archives and the history of Freemasonry.

Susan Mitchell Sommers is Professor of History at St Vincent College in Pennsylvania. She is a distinguished historian of the eighteenth century whose publications include Parliamentary Politics of a County and Town (2002), Thomas Dunckerley and English Freemasonry (2012) and The Siblys of London (2018).

Related Articles published in the Square Magazine

Sankey Lectures 2016

Searching for the Apple Tree: What Happened in 1716?

A video presentation by Andrew Prescott

more….

Roberts’ Constitutions of Freemasonry 1722

Published a year before Anderson’s Constitutions, The Old Constitutions Belonging to the Ancient and Honourable SOCIETY OF Free and Accepted MASONS. Originally printed in London England; Sold by J. Roberts, in Warwick-Lane, MDCCXXII.(1722)

more….

Origins and Links to English Freemasonry – Part 1

Unexpected links between the Freemasonry of today with the original Operative builders.

more….

Ashlar Chippings

Hugh O’Neill’s regular chippings whilst smoothing the ashlar:- Tercentenary of United Grand Lodge of England – 1721-2021 season 2

more….

Masonic Miscellanies

Will the real James Anderson please stand up?

more….

Book Review – Anderson’s Constitutions – 1723This book contains a faithful reproduction of the first edition of the Constitutions of the Free-Masons, printed in London in 1723. The text, word spelling and paragraph size has been maintained, original restored decorations have been used, and font and character typesets have been carefully replicated.

more….

Masonic Blogs – 1723 constitutions

1723constitutions.com/ masonic blog marks the tercentenary of the publication in London of The Constitutions of the Freemasons – the ‘1723 Constitutions’

more….

Book Review – Inventing the Future

This book sets out those principles, considers the people involved and explores the framework within which their ideas were formed. And it discusses how the Constitutions evolved. – By Ric Berman

more….

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device