Woman and Freemasonry by Dudley Wright (1922)

First published by William Rider & Son, Ltd.

Open ye gates, receive the fair who shares

With equal sense our happiness and cares:

Then, charming females, there behold

What massy stores of burnish’d gold,

Yet richer is our art;

Not all the Orient gems that shine,

Nor treasures of rich Ophir’s mine,

Excel the Mason’s heart

True to the fair, he honours more

Than glitt’ring gems, or brightest ore,

The plighted pledge of love;

To every tie of honour bound,

in love and friendship constant found,

And favoured from above.

Secret societies have always held a fascination for both sexes, despite the fallacy that women cannot keep a secret.

Women, it is claimed by Masonic historians and writers, have always been rigidly excluded from the ranks of Orthodox Masonry both Operative and Speculative, although, as will be seen in the course of the following pages, the barriers have been pierced on more than one occasion.

The first Book of Constitutions of the Grand Lodge of England, published in 1723, expressly stipulated that no woman should be admitted as a member of a Masonic Lodge.

In this edition Dr. Anderson stated that ‘the learned and magnanimous Queen Elizabeth, who encourag’d other Arts, discourag’d this; because, being a Woman, she could not be made a Mason, tho’, as other great Women, she might have much employ’d Masons, like Semiramis and Artemisia’.

Dr. Anderson also goes on to say:

Elizabeth being jealous of any Assemblies of her Subjects, whose Business she was not duly appris’d of, attempted to break up the Annual Communication of Masons, as dangerous to her Government.

But Masons have transmitted it by Tradition, when the noble Persons her Majesty had commissioned, and brought a sufficient Posse with them at York, on St. John’s Day, were once admitted into the Lodge, they made no use of Arms, and returned the Queen a most honourable Account of the ancient Fraternity, whereby her political fears and doubts were dispell’d, and she let them alone, as a People much respected by the Noble and the Wise of all the polite Nations, but neglected the Art all her Reign.

In an edition of the Book of Constitutions, published in 1738, Dr. Anderson gives further particulars of this incident in the following words:

Now Learning of all Sorts revived, and the good old Augustan Style began to peep from under its rubbish.

And it would have soon made great progress if the Queen had affected Architecture.

But hearing the Masons had certain secrets that could not be reveal’d to her (for that she could not be Grand Master) and being jealous of all Secret Assemblies, she sent an armed force to break up their annual Grand Lodge at York, on St. John’s Day, 27th December, 1561.

But Sir Thomas Sackville, Grand Master, took care to make some of the chief men sent Free‑Masons, who then joining in that Communication, made a very honourable report to the Queen, and she never more attempted to dislodge or distrust them, but esteem’d them as a peculiar sort of men that cultivated peace and friendship, arts and science, without meddling in the affairs of Church and State.

Queen Elizabeth I is credited with being the only woman initiated into the Order of Buffaloes. [ED. See note below]

The pages of history show that in past ages women had their own secret societies.

In some instances, man was excluded as rigorously as woman is excluded from modern Orthodox Freemasonry.

In others, men were admitted on equal, or almost equal, terms with the gentler sex.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were introduced by Eumelpus in 1356 B.C., and were founded in honour of Ceres and Proserpine, and anyone violating the Oath taken on admission and revealing the secrets to the uninitiated was punished with death.

The like punishment was meted out to uninitiated intruders at the ceremonies.

Into these Mysteries both sexes were eligible for initiation, and there was no age limit.

The Greek festival of the Thesmophoria held in the month of Pyanepsion (October) in honour of the goddess Demeter lasted for five days, and only women were permitted to take part in it.

They had to undergo a solemn preparation for the Festival, preparation extending over nine days, during which time they kept apart from their husbands and purified themselves in various ways.

The sanctuary, where the Mysteries took place, was at Kalamai. The days were spent in bathing in the sea, the Mysteries being celebrated at night.

One of days was spent in fasting, when the women sat on the ground, wearing mourning attire and singing dirges.

Swine were also offered in sacrifice the infernal gods. Participation in the Festival was limited strictly to married women who were full citizens.

Gibbon, in his History of Rome, records a female Order in the fourth century.

It was customary for the Roman ladies annually to celebrate in the house, either of the Consul or Praetor, certain rites and ceremonies in honour of a goddess.

In what the adoration consisted, as no man was ever permitted to be present, or even to be made acquainted with the nature or tendency of the function, it is impossible to say.

At the appointed time the vestals came, and so cautious were they as to privacy that the house was carefully searched, all male animals were turned out of doors, and even statues and pictures of men were covered with thick opaque veils.

The only attempt made to violate the caution of the Roman matrons at the celebration of this secret ceremony occurred during the Praetorship of Julius Caesar in 692.

His third consort, Pompeia, was united to him more from policy than inclination, and notwithstanding the nuptial vow she had taken, she retained an admirer, Clodius, belonging to a noble family in the annals of that republic.

Aurelia, the mother of Caesar, discovered the attachment of Pompeia, and to protect the honour of her son, by her vigilance prevented interviews between Pompeia and her lover.

At the expiration of the consular year the secret festival was to be performed, as customary, in the house of Caesar, he being the chief magistrate at that time, and to his consort belonged the right of presiding at the ceremony.

This was a triumph for Pompeia, who conceived the idea of concealing her favourite in the house and gratifying his oft-expressed wish of witnessing the sacred rites.

Clodius, by arrangement, disguised himself in the garb of a female and at night proceeded towards the house of his admirer.

A confidential servant who was in the secret whispered to Clodius that it was her mistress’s desire that he should secret in her chamber.

He repaired thither, but tired of waiting he wandered into an adjacent apartment, when he was accosted.

Anxious to avoid conversation, he turned away, but was followed and a demand made for his name and the reason of his presence there.

As he refused to give my answer or explanation he was arrested and prosecuted at the public tribunal.

The Roman criminal code had definitely affixed the punishment of death for any man to be present at the ceremony, but by reason of his influence in the Senate, the certainty of his not having attained to the most distant knowledge of the Mysteries, and his open avowal that his object was solely that he might be favoured with a sight of Pompeia, he was acquitted.

Pompeia’s indiscretion was punished by Caesar’s divorcing her, assigning, as a reason, ‘that his wife ought to preserve herself from the suspicion as well the guilt of crime’.

With regard to the androgynous societies, L’ Abbe Clavel, in his History of Freemasonry and Similar Societies, Ancient and Modern, published in 1842, says that:

Freemasons embraced these Societies with enthusiasm as a practical means of giving to their wives and daughters some share of the pleasures which they themselves enjoyed in their mystical assemblies.

And this, at least, may be said of them that they practised with commendable fidelity and diligence, the greatest of the Masonic virtues, and that the banquets and balls which always formed an important part of their ceremonial were distinguished by numerous acts of charity.

With regard to the androgynous societies, L’ Abbe Clavel, in his History of Freemasonry and Similar Societies, Ancient and Modern, published in 1842, says that:

Freemasons embraced these Societies with enthusiasm as a practical means of giving to their wives and daughters some share of the pleasures which they themselves enjoyed in their mystical assemblies.

And this, at least, may be said of them that they practised with commendable fidelity and diligence, the greatest of the Masonic virtues, and that the banquets and balls which always formed an important part of their ceremonial were distinguished by numerous acts of charity.

In this connection, however, it may be permissible to draw attention to an article bearing on this subject which appeared in the Daily Telegraph of 14th April, 1920, in the course of which the writer said:

One more masculine stronghold has, we are informed, fallen to the monstrous regiment of women. The Grand Lodge of French Freemasons has declared itself in favour of the admission of women to the craft.

It is, of course, true that a female Freemason would not be a creature absolutely without precedent. There is respectable evidence for the initiation of a woman in that century momentous in the fortunes of Masonry – the eighteenth.

Misogynists may derive what comfort they please from the fact that the traditional woman Freemason was initiated, if anywhere, in Ireland.

They can undoubtedly contend that to open the fraternity to women would be a revolutionary change of policy.

That the decision of French Freemasons will have much influence on the craft in England is not probable.

In France membership has been associated with religious and political opinions which are either antagonistic or irrelevant to the principles of English Freemasonry.

The fact, indeed, makes the proposal to admit women more remarkable, for hitherto women have nowhere given much support to anti‑clerical or anti‑theistic parties.

Whether it portends a new orientation of the Grand Orient we will not now inquire. It would be impertinent to offer any advice to our Freemasons on a question of the constitution of their own fraternity.

The most enthusiastic feminist may be content to admit that there is justification for the existence of societies confined to one sex.

Such organisations have existed from the dawn of time, and women have eagerly maintained the exclusiveness of their own.

But only an obscurantist would argue that the secrets of any fraternity are endangered by the admission of women.

A social system which continually increases the number of women secretaries is sufficient evidence of the folly of that ancient libel.

The splendid works of charity which are the glory of English Freemasonry may suggest that ‘ women would be well fitted for membership of the craft.

It might be argued, on the other hand, that a society composed of both sexes, however valuable, however pleasant, would inevitably lose some of the valued qualities of a male fraternity.

Just as affectionate and devoted wives have been known to thank Providence ‘ for the existence of their husbands’ clubs, we suspect that many women would prefer the men of their families to enjoy the delights of the Masonic Lodge alone.

Though shut from our Lodges by ancient decree,

In spite of our laws, here woman has part;

For each Mason, I’m sure, will tell you with me,

Her form is enshrined and reigns in our heart.

‘Twas wisely ordained by our Order of old

To fasten the door, which entrance denies;

For once in our Lodge she would rule uncontrolled,

And govern the Craft by the light of her eyes.

Editor’s Notes:

The question of whether Queen Elizabeth I was a member of any such Order is spurious considering the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes (RAOB) was founded in 1822. Dudley Wright most likely took that assumption from a passage in the First Degree ceremony of the ROAB, where it states:

In the Sixteenth Century, Elizabeth, Queen of England, being satisfied that the principles of our Order were of great benefit to the Community, as well as a strong support to any well-regulated Government, presented us with a Banner, bearing the Motto, “Nemo Mortalium Omnibus Horis Sapit,” which being freely interpreted means, “Mortals are not wise at all hours.”

Source of ritual: http://www.stichtingargus.nl/vrijmetselarij/raob_r1.html

Dudley Wright

Not much is known about Dudley Wright but I came across this interesting article by scholar Simon Mayers

Dudley Wright was an individual who refused to embrace the modern spirit of secularisation and cultural “disenchantment,” countering it instead with a quest to find esoteric wisdom, spiritual “truth,” and an “original” ur-religion or prisca theologia. As a Freemason, Dudley Wright was a member of several lodges, and was on the editorial team of a number of prominent Masonic periodicals. For several years he was the assistant editor, and briefly the principal editor, of the main English Masonic newspaper, The Freemason, and was the founder-editor of The Masonic News. He was also on the editorial team of a number of other Masonic periodicals, such as The Builder and The Master Mason. He published several books and dozens of articles about various aspects of Freemasonry. In addition to his works on Freemasonry, Wright also published articles and books on various religious, theosophical, spiritual and esoteric traditions. He also had a keen interest in psychic and supernatural phenomena, and wrote many articles and books on vampires, poltergeists, the after-life, and resurrection. He was – to use his own phrase – a “truth-seeker” on a spiritual journey.

Read the full article HERE

Article by: Philippa Lee. Editor

Philippa Lee (writes as Philippa Faulks) is the author of eight books, an editor and researcher.

Philippa was initiated into the Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons (HFAF) in 2014.

Her specialism is ancient Egypt, Freemasonry, comparative religions and social history. She has several books in progress on the subject of ancient and modern Egypt. Selection of Books Online at Amazon

Recent Articles: Women Freemasons

Freemasonry and Women's Rights - P4 The Freemason judge who ruled women were 'persons' |

Freemasonry and Women's Rights - P3 Who embraced and influenced the women’s rights and suffragette movements in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century |

Freemasonry and Women's Rights - P2 Second part, in the introductory series exploring the history of mixed, Co- and female Freemasonry, and how the fraternity and its members helped progress the emancipation and rights of women. |

Freemasonry and Women's Rights - P1 A two-part introductory series exploring the history of mixed, Co- and female Freemasonry, and how the fraternity and its members helped progress the emancipation and rights of women. |

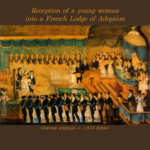

Adoniramite Freemasonry, also known as Adoptive Freemasonry, emerged in 18th-century France as a unique initiation system for women. Mimicking the secrecy and symbolism of regular Freemasonry, these Lodges of Adoption attracted noblewomen, literary figures, and even royalty. Explore the origins, rituals, and controversies surrounding this intriguing branch of Freemasonry. |

Two ladies who became Grand Masters Who were the two ladies, mother and daughter who become Grand Masters of Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Freemasons |

A look at Adoptive Lodges that were established in France for the initiation of females; a short Extract from the Encyclopedia Of Freemasonry |

Published in 1922, this interesting, and whimsical book was penned by Dudley Wright |

Look at the History of Women in Freemasonry. Although Several women had been introduced to Freemasonry prior to the 18th century, it was more by accident than invitation. |

The Great American Experiment, a film by HFAF documenting the Consecration and Installation of Officers of America Lodge No. 57 on May 25, 2019 |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device