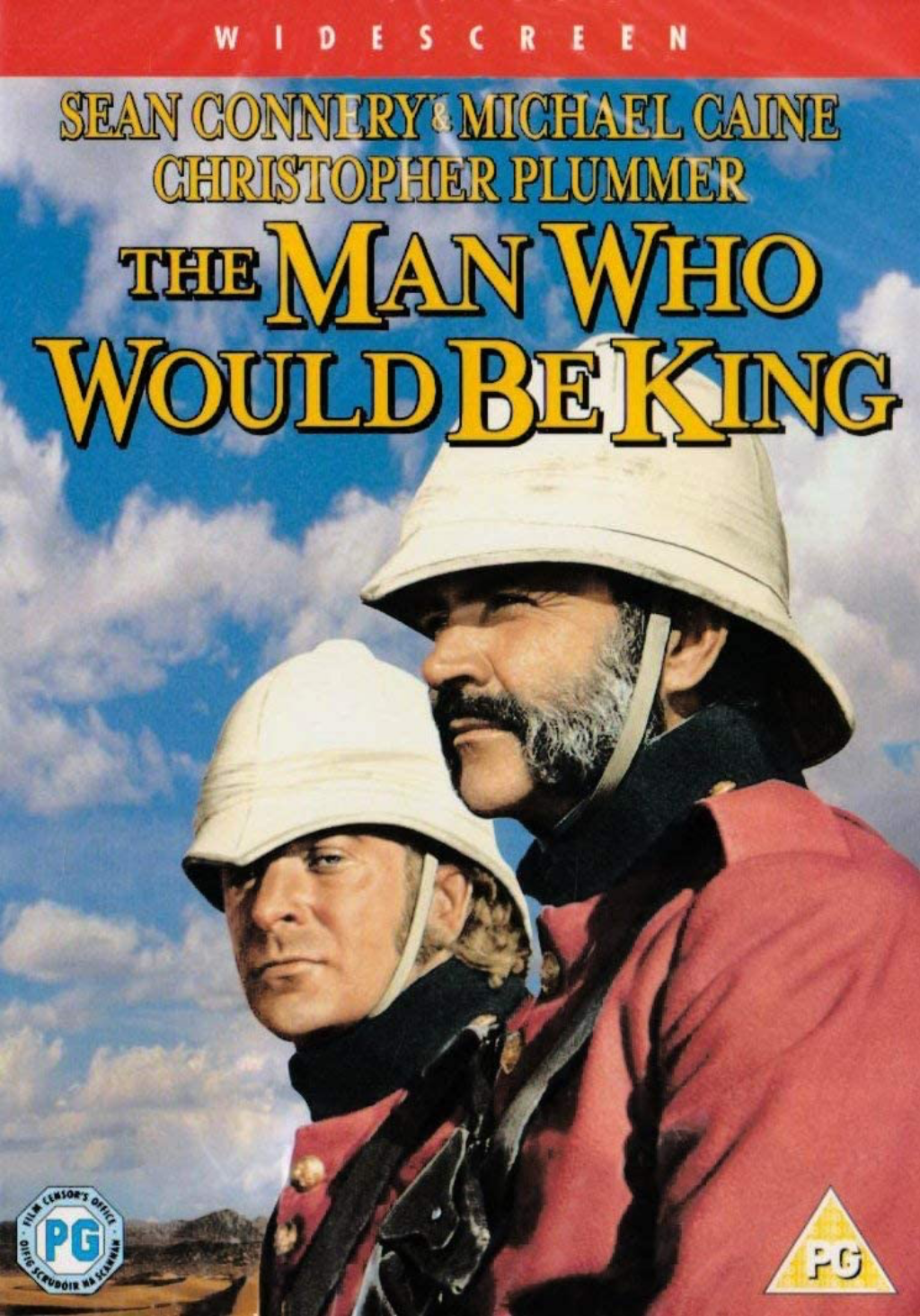

Masonry is the cornerstone of Kipling’s best novel Kim, and the key to his finest long story The Man Who Would be King.

His interest in Freemasonry is easily recognised in much of his work and examples are too numerous for one article.

In his short stories and poems, he often used words from the ritual and in his later short stories he often uses the lodge meeting as a vehicle through which to tell the story.

After Mozart, I would choose Kipling as the most creative Freemason in our three-hundred-year history. Mozart’s interest in the Craft is well documented from the company he kept in Vienna in the 1780s, and the lodges he joined and attended. In addition to The Magic Flute, he composed music for specific Masonic ceremonies including one for his own father’s second ceremony. But Kipling’s Masonic life is much more puzzling and largely unresearched and the sources of his Masonic material largely untraced. Sadly, lectures he gave to his mother lodge have been lost.

Rudyard Kipling became a Freemason in India in 1885 at 20 years old, given a dispensation by the District Grand Master and was almost immediately appointed as the Secretary of his mother lodge, Hope and Perseverance No.782 (E.C.) United Grand Lodge of England still has the original annual returns he signed.

When he left India after his early successes, he ceased to be an active Freemason although still only 24, but he never severed his connections with the Craft. Those four years made a huge impact on his life and work. He lived in the USA and England and travelled extensively. Except for one single recorded visit he never attended another Lodge meeting after he left India. On this occasion he visited Rosemary Lodge No.2851, London, in 1924 as a guest of his next-door neighbour Colonel Sutherland-Harris. Yet, for the next 45 years of his life, Masonry featured in his work and was often the driving force behind his narratives and thinking.

Despite his non-attendance at meetings, he was a founder member of several lodges, including one created to support the Imperial War Graves Commission – Builders of the Silent Cities No. 4948 – where his signature appears on the warrant. Despite this, he did distance himself from any active involvement. So where did he find his ideas?

I found one of the answers to this enigma in the archives at Freemasons’ Hall.

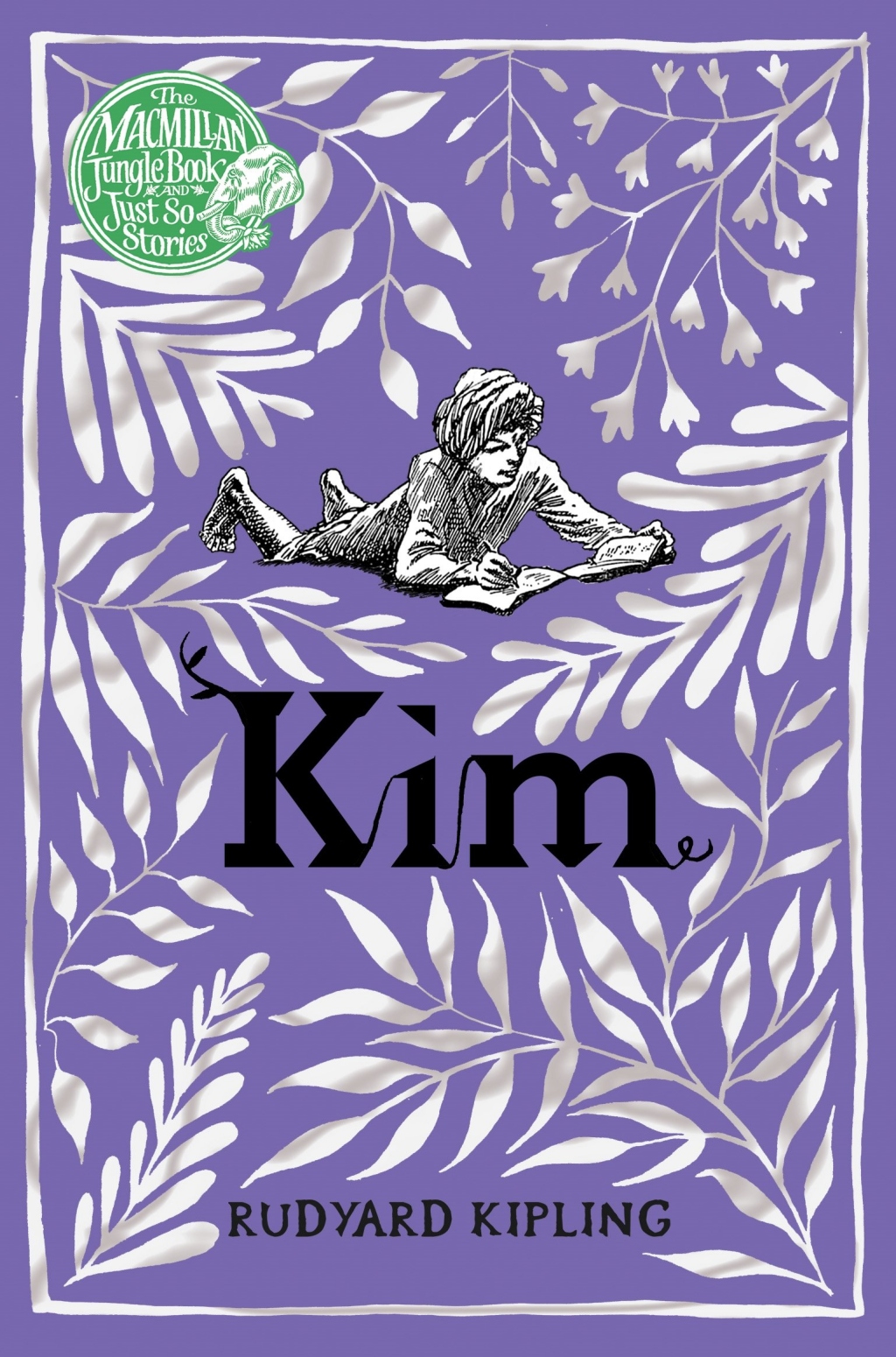

The biggest puzzle was the source of the story of Kim. It is undoubtedly the finest picture we have of late Victorian India, after the Indian Mutiny but before the Raj starts to disintegrate.

On the very first page of the book, we meet the boy Kim whom we are told is “a poor white of the very poorest”.

Both his parents are dead. His mother, like many British in India, died of cholera. His father had been a colour sergeant in an Irish regiment, who on leaving the army became addicted to opium.

All he left Kim were three pieces of paper: his ne varietur, his clearance certificate and his birth certificate. Before he died, he urged Kim (still only a child) that he must hang on to these papers as one day everything would come right and he “would be exalted between pillars – monstrous pillars – of beauty and strength”.

His father said that the papers belonged “to a great piece of magic – such magic as men practised over yonder behind the Museum, in the big blue-and-white Jadoo-Gher – the Magic House, as we name the Masonic Lodge”.

Kim lives on his wits in the bazaars of Lahore and he carries these papers sewn into an amulet around his neck.

His father had promised that “they will come for you a great Red Bull on a green field and the Colonel riding on his tall horse”. Kim does not realise that this refers to the flag of his father’s old regiment, and the lodge he joined as a member of it. As the story unfolds, the Regiment do find him.

On examining the amulet, they realise he is the son of one of their former comrades. and as his father was a Freemason, Kim’s future is assured as the Regiment takes responsibility for the orphan child.

This is only the start of Kim’s adventures as he travels India with the Lama, the holy man who becomes his mentor, and shares Kim’s education with the members of the Regiment.

Kim after his schooling, goes to work for the British and becomes involved in the Great Game, the conflict between the British and the Russians on India’s northern borders.

Kim’s adventures make a wonderful story for readers of any age.

So, where did Kipling get the idea of an orphan child and his education being funded by his father’s old comrades? The answer is that the idea came from his work as Charity Secretary of his lodge.

The story may sound romantic and fanciful, but I found the source of it, buried deep in the archives at Great Queen Street.

It seems his idea of a Regimental lodge supporting orphans and widows was normal practice. So harsh were conditions in India for the British in the nineteenth century, that death rates were horribly high. Almost one third of the soldiers and administrators died leaving impecunious widows and orphans.

The children were often educated at the Regiment’s expense or repatriated to England. Kipling’s Lodge was actively involved in raising money for them. The Masonic Yearbooks for the Punjab in the 1880s list the lodges and their contributions to this charitable work.

Illustration of a begging leper and pariah dogs, to give an example of Kipling’s ‘Outcastes’ and showing relationships between people and animals in India.

IMAGE CREDIT: Wellcome Digital Collection – Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In 1887, the charity account for his lodge in Lahore was called “The Educational Fund of Lodge Hope and Perseverance”, and in the yearbook it shows J. Rudyard Kipling as the Charity Steward, and his and other brethren’s contributions to the fund.

Each yearbook lists the funds raised by individual lodges and the numbers of widows and orphans they helped. By 1888, Kipling had moved from Lahore to Allahabad and joined another lodge there. The yearbooks list the number of children supported, to which schools they were sent and the cost per child. In this period the Punjab District regularly supported up to forty children at any one time, apart from those too young to leave their mothers.

From his work as a Charity Steward, Kipling would have been familiar with problems of orphaned British children in India and it is not a huge leap to see that this was one of the ideas for the plot of Kim. By the time Kipling left India in March 1889, he was already an established writer but his experiences in Freemasonry would continue to influence his writing for the rest of his life

Kipling did attend one meeting of Rosemary Lodge No.2851 in London in 1924, as a guest of his next-door neighbour Colonel Sutherland-Harris, although I was told it was thought he only went to the festive board! I obtained a copy of the page in the Tyler’s book where Kipling’s very familiar signature appears and he signed as a visitor from Motherland Lodge No.3861, although there is no evidence that he ever visited that lodge.

Article by: Richard Jaffa

Richard Jaffa who is a Past Junior Grand Deacon of UGLE and a Past Assistant Provincial Grand Master of Warwickshire. His mother lodge in St. Paul’s Lodge No.43 founded in 1733; he is also a member of Lodge of Jurisprudence No. 9457 and Earl Spencer Lodge No. 1420. He is a retired lawyer and journalist.

Man and Mason – Rudyard Kipling by Richard Jaffa is available from all good bookshops and Amazon Online

Man And Mason-Rudyard Kipling

By: Richard Jaffa (Author)

Rudyard Kipling remains one of the most intriguing and elusive personalities in English literature. He was a Nobel laureate, prolific writer, political figure and one of the outstanding men of his era.

There are many dimensions to his work but no-one has previously examined in depth his interest in Freemasonry and its impact on his literary output.

This book looks at the life of both the young Kipling and the old one and shows how, at two major stages of his life he turned to Freemasonry, not only for dramatic impact, but also as a source of spiritual comfort after the horrors of the First World War.

Recent Articles: by Kipling

‘ONCE in so often,’ King Solomon said, Watching his quarrymen drill the stone… |

When I was a King and a Mason, a Master Proven and skilled, |

Every man must be his own law in his own work, but it is a poor-spirited artist in any craft who does not know how the other man’s work should be done or could be improved. |

Rudyard Kipling's deep connection with Freemasonry is evident in many of his poems and his stories |

Kipling's In the Interests of the Brethren Short story by Rudyard Kipling |

Kipling’s critics are quick to include him as one of the ‘fathers’ who ‘lied’ – echoing his short poem ‘Common Form’ – ‘If any question why we died, Tell them, because our fathers lied’. |

Kipling's interest in Freemasonry is easily recognised in much of his work and examples are too numerous for one article. |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device