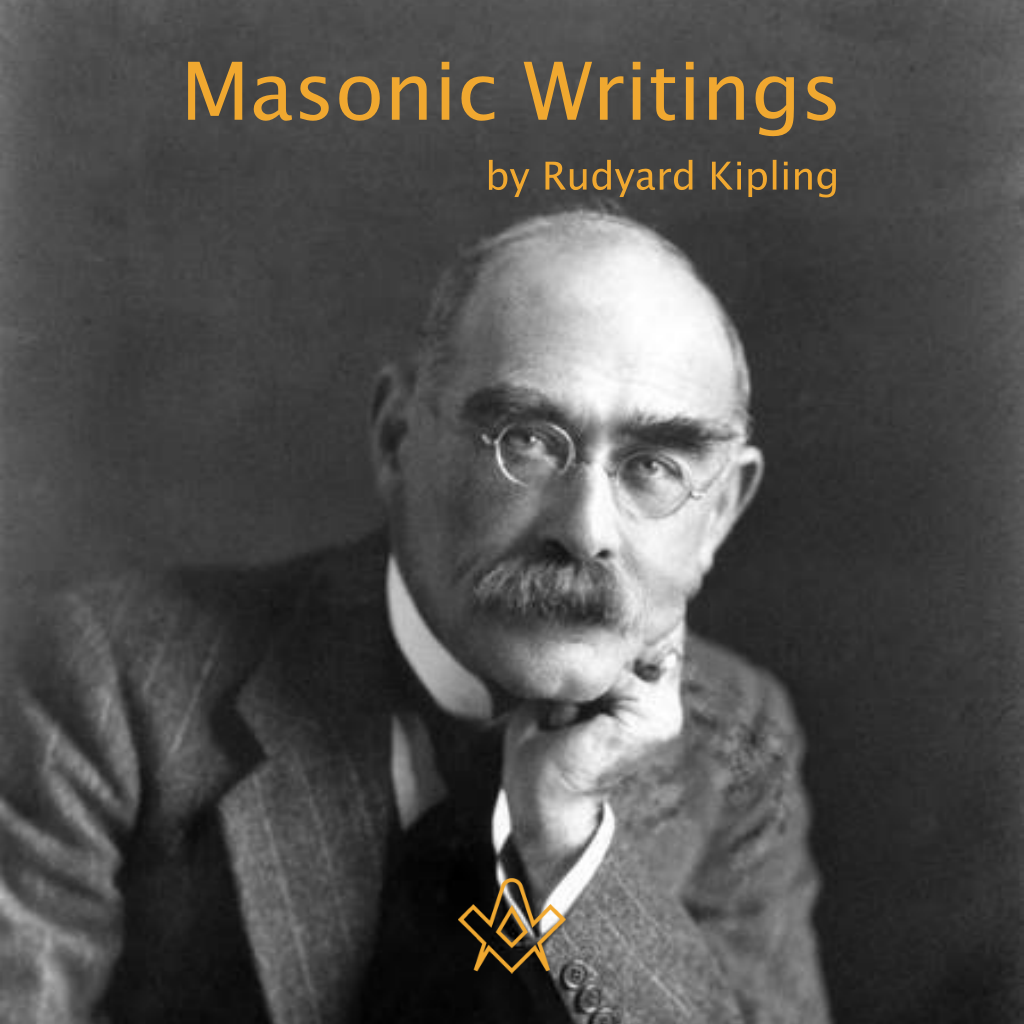

Rudyard Kipling’s deep connection with Freemasonry is evident in many of his poems – The Mother Lodge, King Solomon’s Banquet, If, L’Envoi, The Palace – and his stories Kim, and The Man Who Would Be King.

In Chapter Three of Something of Myself, Kipling wrote of his initiation into Freemasonry in Lahore, India:

In ’85 I was made a Freemason by dispensation (Lodge Hope and Perseverance 782 E.C.), being under age, because the Lodge hoped for a good Secretary. They did not get him, but I helped, and got the Father to advise, in decorating the bare walls of the Masonic Hall with hangings after the prescription of Solomon’s Temple. Here I met Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, members of the Arya and Brahmo Samaj, and a Jew tyler, who was priest and butcher to his little community in the city. So yet another world opened to me which I needed.

This multi-cultural experience was a meaningful one for him, and he confirmed this later in a letter to The Times:

‘I was Secretary for some years of the Lodge . . . , which included Brethren of at least four creeds. I was entered by a member from Brahmo Somaj, a Hindu, passed by a Mohammedan, and raised by an Englishman. Our Tyler was an Indian Jew.’

Sir George MacMunn, a British General, scholar and one of the founders of The Kipling Society wrote:

Kipling uses Masonry in much the same way he uses the Holy Writ, for the beauty of the story, for the force of the reference, and for the dignity, beauty, and assertiveness of the phrase. There is one more effect that familiarity denies us which is present in the Masonic allusion and that is the almost uncanny hint of something unveiled.

Kipling has often been accused of racism but if you understand the language of the time, you can understand that there is affection and not ridicule in his descriptions of the members of his lodge.

His writing was lyrical yet direct, often slipping into the vernacular to make a point, or to distinguish speech from one man to the next.

But to describe him as a racist is vastly off the mark; in fact Kipling probably experienced – and appreciated – a far more multicultural environment than many of us do today.

In this introduction to Kipling’s Masonic writings, we look at a poem that most Masons will probably have heard of, if not heard – The Mother Lodge.

It beautifully describes a lodge filled with men of all colours and creeds, from all walks of life – ‘Outside — “Sergeant! Sir! Salute! Salaam!” Inside – “Brother” an ‘it doesn’t do no ‘arm’ – who, ‘met upon the Level an’ parted on the Square’.

His use of the vernacular (the language or dialect spoken by the ordinary people in a particular country or region) is not to deride or ridicule, it was intended to ‘speak’ for the common man, to demonstrate that within the lodge it didn’t matter if you were a Lord or his butler, everyone was catered for and all religions, castes and ethnicities embraced.

It speaks volumes of the brotherly love, relief and truth, for which all Freemasons strive.

The Mother Lodge

There was Rundle, Station Master,

An’ Beazeley of the Rail,

An’ ‘Ackman, Commissariat,

An’ Donkin’ o’ the Jail;

An’ Blake, Conductor-Sargent,

Our Master twice was ‘e,

With ‘im that kept the Europe-shop,

Old Framjee Eduljee.

Outside – “Sergeant! Sir! Salute! Salaam!”

Inside – “Brother”, an’ it doesn’t do no ‘arm.

We met upon the Level an’ we parted on the Square,

An’ I was Junior Deacon in my Mother-Lodge out there!

We’d Bola Nath, Accountant,

An’ Saul the Aden Jew,

An’ Din Mohammed, draughtsman

Of the Survey Office too;

There was Babu Chuckerbutty,

An’ Amir Singh the Sikh,

An’ Castro from the fittin’-sheds,

The Roman Catholick!

We ‘adn’t good regalia,

An’ our Lodge was old an’ bare,

But we knew the Ancient Landmarks,

An’ we kep’ ’em to a hair;

An’ lookin’ on it backwards

It often strikes me thus,

There ain’t such things as infidels,

Excep’, per’aps, it’s us.

For monthly, after Labour,

We’d all sit down and smoke

(We dursn’t give no banquits,

Lest a Brother’s caste were broke),

An’ man on man got talkin’

Religion an’ the rest,

An’ every man comparin’

Of the God ‘e knew the best.

So man on man got talkin’,

An’ not a Brother stirred

Till mornin’ waked the parrots

An’ that dam’ brain-fever-bird;

We’d say ’twas ‘ighly curious,

An’ we’d all ride ‘ome to bed,

With Mo’ammed, God, an’ Shiva

Changin’ pickets in our ‘ead.

Full oft on Guv’ment service

This rovin’ foot ‘ath pressed,

An’ bore fraternal greetin’s

To the Lodges east an’ west,

Accordin’ as commanded

From Kohat to Singapore,

But I wish that I might see them

In my Mother-Lodge once more!

I wish that I might see them,

My Brethren black an’ brown,

With the trichies smellin’ pleasant

An’ the hog-darn passin’ down; [Cigar-lighter]

An’ the old khansamah snorin’ [Butler]

On the bottle-khana floor, [Pantry]

Like a Master in good standing

With my Mother-Lodge once more!

Outside – “Sergeant! Sir! Salute! Salaam!”

Inside – “Brother”, an’ it doesn’t do no ‘arm.

We met upon the Level an’ we parted on the Square,

An’ I was Junior Deacon in my Mother-Lodge out there!

Listen to the poem, beautifully read by Jonathan Jones, the Farnham Town Crier

Recent Articles: by Kipling

‘ONCE in so often,’ King Solomon said, Watching his quarrymen drill the stone… |

When I was a King and a Mason, a Master Proven and skilled, |

Every man must be his own law in his own work, but it is a poor-spirited artist in any craft who does not know how the other man’s work should be done or could be improved. |

Rudyard Kipling's deep connection with Freemasonry is evident in many of his poems and his stories |

Kipling's In the Interests of the Brethren Short story by Rudyard Kipling |

Kipling’s critics are quick to include him as one of the ‘fathers’ who ‘lied’ – echoing his short poem ‘Common Form’ – ‘If any question why we died, Tell them, because our fathers lied’. |

Kipling's interest in Freemasonry is easily recognised in much of his work and examples are too numerous for one article. |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device