The reputation of the Huguenot Freemason, Dr John Misaubin, has been buffeted by waves of criticism for the best part of three hundred years.

His transgression? Being a quack.

Wikipedia defines a quack as a ‘fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill’ or ‘a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, qualification or credentials they do not possess’.

The term quack is an abbreviated form of quacksalver, from the Dutch: kwakzalver a ‘hawker of salve’.

In the Middle Ages the quacksalvers sold their wares on the market, shouting loudly to advertise them.

Not surprisingly, quacks have provided a rich source of material for satirical cartoonists.

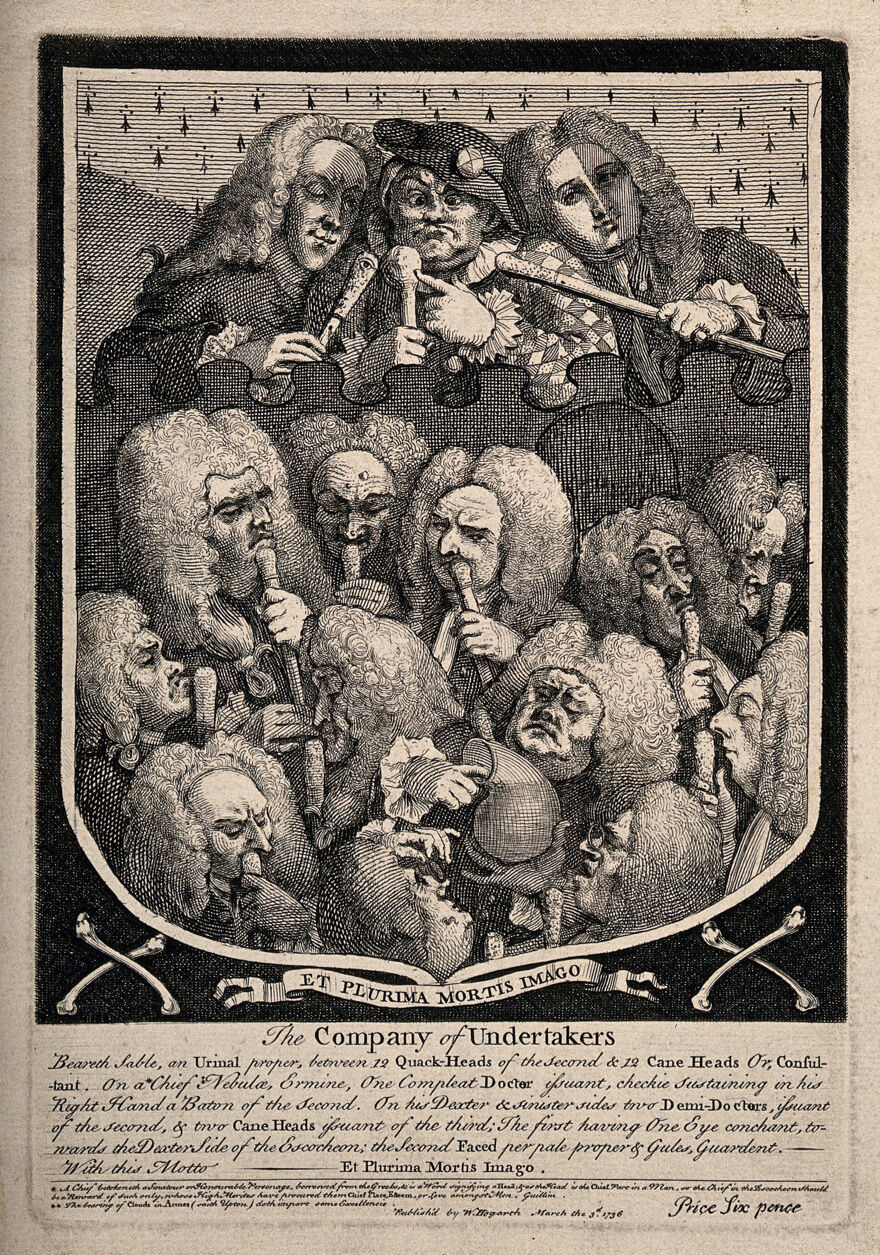

The Company of Undertakers an engraving by William Hogarth is a dig at the medical profession, and, in particular, dodgy doctors, whom Hogarth has no hesitation in labelling quacks.

The engraving has a black border in the style of a mourning card.

A coat of arms is suggested by sinister crossbones in the bottom left and right-hand corners, and a pretentious motto in Latin, Et Plurima mortis imago – ‘And many an image of Death’, gives spurious legitimacy to the coat of arms.

The Company of Undertakers – A shield containing a group portrait of various doctors and quacks, including Mrs Mapp, Dr Joshua Ward and John Taylor. Etching by W. Hogarth, 1736, after himself.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The three doctors at the top of the image were based on actual physicians.

The doctor dressed as a clown, in the middle of the trio, was actually a woman, Sarah Mapp, a well-known bone setter. The physician to her left was based on Joshua Ward (‘Spot Ward), a doctor who had a birth mark on one side of his face.

John Taylor, a prominent oculist, was placed to the right of Sarah Mapp. Most of the twelve quacks in the rest of the picture are sniffing the ends of their canes, which would have contained a disinfectant, in the manner of a vinaigrette used by members of the public to combat the unwelcome smells of the street.

Three physicians in the lower section of the engraving are examining the contents of a urine flask with a range of facial reactions.

Left: Sarah Mapp. Coloured etching by G. Cruikshank, 1819, after W. Hogarth.

Centre: John Taylor. Mezzotint by J. Faber, junior, after P. Ryche

Right: Joshua Ward. Coloured line engraving, 1820, after T. Bardwell

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

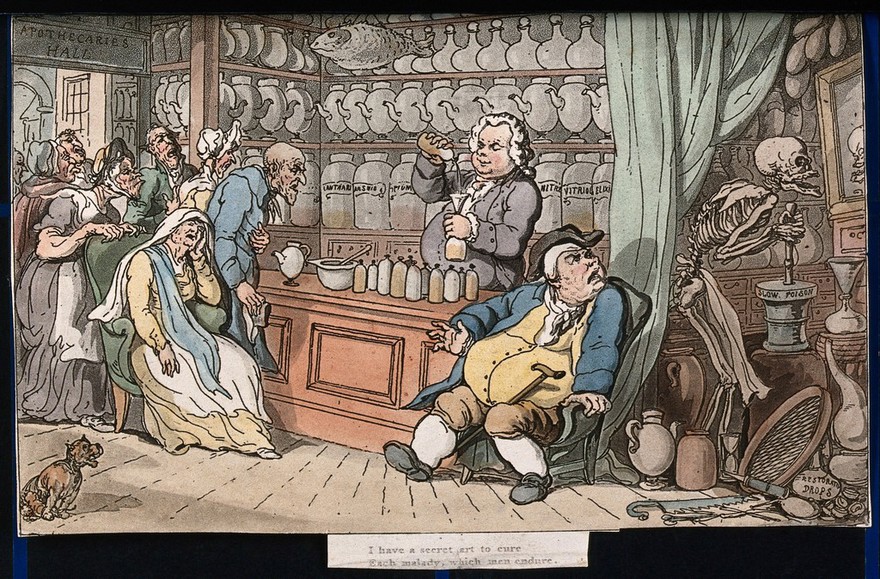

Apothecaries were often labelled as quacks, as depicted in the biting satire of Thomas Rowlandson’s illustration mercilessly entitled ‘The Dance of Death: the apothecary’.

The dance of death: the apothecary. Coloured aquatint by T. Rowlandson, 1816.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

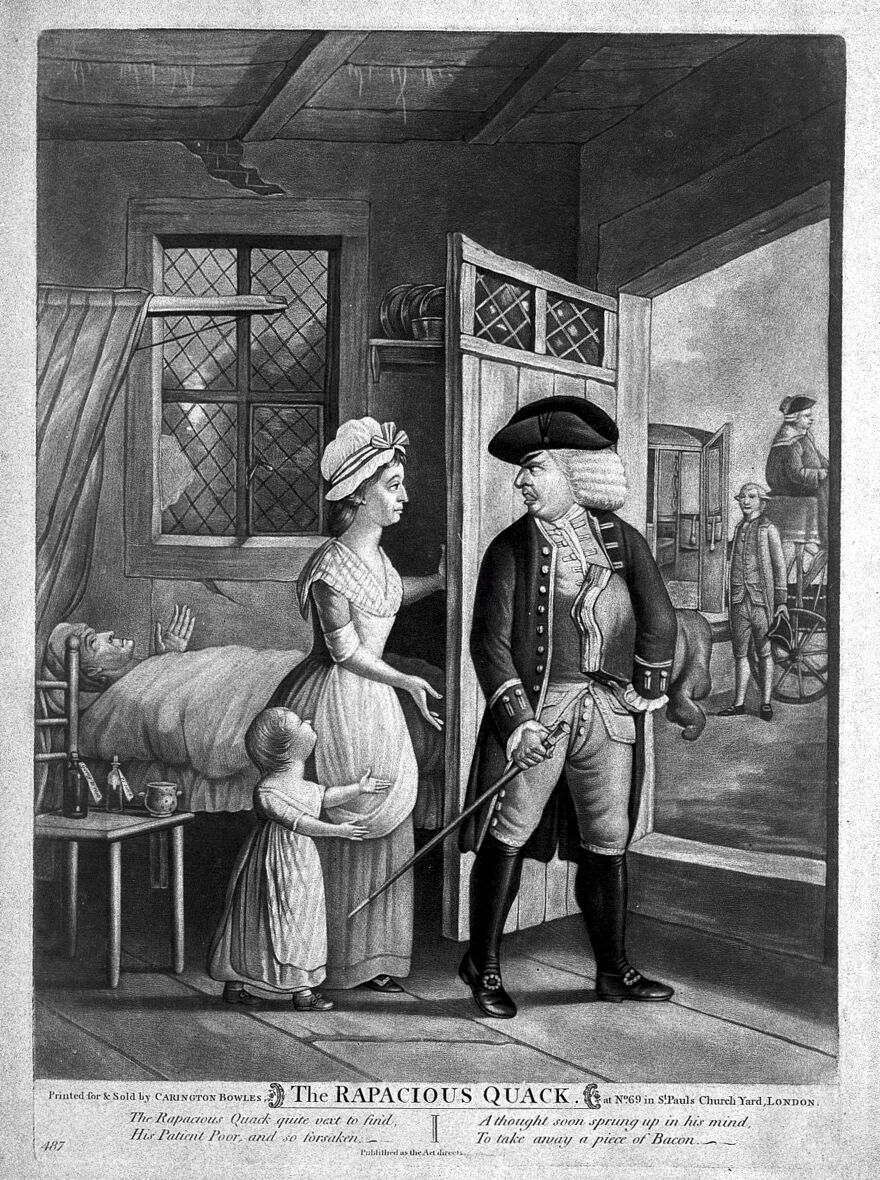

Quacks were perceived to engage in a heartless pursuit of money as depicted in the satirical cartoon The Rapacious Quack.

James Bramston took a satirical swipe at Misaubin in his poem The Man of Taste, published in London in 1733:

Should I perchance be fashionably ill,

I’d send for Misaubin, and take his pill.

I should abhor, though in the utmost need,

Arbuthnot, Hollins, Wigan, Lee, or Mead:

But if I found that I grew worse and worse,

I’d turn off Misaubin and take a Nurse.

How oft, when eminent physicians fail,

Do good old women’s remedies prevail?

A greedy medical practitioner demanding a leg of bacon for payment from a poor family. Mezzotint.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Misaubin had the misfortune to be readily identifiable in a number of satirical engravings by Hogarth, despite the fact that they were both Freemasons.

Tall and spindly, he was ridiculed for his fondness for alcohol, his outlandish manners, and his thick French accent.

He was the model for one of the doctors in William Hogarth‘s The Harlot’s Progress (Plate 5), and he is held up for ridicule in Henry Fielding‘s Tom Jones, where he is supposed to have said:

![]()

Bygar, me believe my pation take me for de undertaker, for dey never send for me till de physicion have kill dem.

Fielding also says that Misaubin told people to address letters to him as ‘To Dr Misaubin in the World’ for ‘there were few People in it to whom his great Reputation was not known’.

Fielding chose to satirise Misaubin in the comedy The Mock Doctor which is an adaptation of Molière‘s Le Médecin malgré lui.

However, the text of the comedy is preceded by a rather fulsome, three-page dedication to Dr John Misaubin, suggesting that Fielding may have gone along with the popular prejudice against Misaubin as a means of promoting his play.

If so, it worked. The play was a great success.

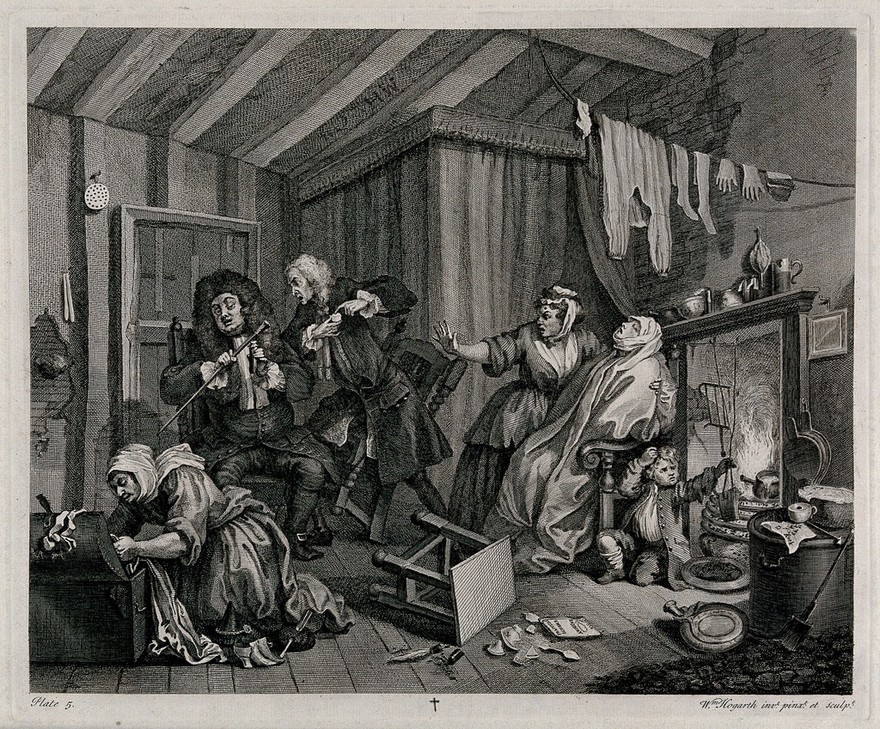

Wrapped in “sweating” blankets and close to the fire Moll Hackabout nears death as two doctors argue. Engraving by William Hogarth.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In the 1732 etching, Misaubin, on the right of the two doctors, is arguing with Dr Richard Rock about the medical treatment to be applied.

Rock favours bleeding, and Misaubin the use of some of his infamous pills.

Each is more interested in getting their own way than attending to their ailing patient, Moll Hackabout, who is probably dying of venereal disease, brought on from her activities as a prostitute.

She is wrapped in a ghostly shroud. The landlady rifles Moll’s possessions, and Moll’s maid appears to be appealing to the doctors to attend to her mistress. Moll’s son sits by the fireplace picking lice out of his hair.

The remains of discarded potions litter the floor. This image of Misaubin’s callous venality has stuck throughout the years.

Fortunately, some of these misconceptions have been corrected by Barry Hoffbrand.

His most recent article about Misaubin was a well-researched paper published in Volume XXX No. 1 of The Huguenot Society Journal, 2013.

Misaubin was born at Mussidan in the Dordogne in 1673.

His father was a Protestant clergyman who subsequently preached at the French Church in Spitalfields. Misaubin qualified as a medical doctor at Cahors.

He arrived in England with his father in 1701, where they made their reconnaisance, a public avowal of faith necessary for their admission to communion at the Savoy Church.

Before 1685, and the revocation of the Treaty of Nantes, Protestant refugees from France would bring with them a Tesmoinages, a certificate of sound doctrine and good behaviour issued by their former church.

After 1685 there were no Protestant churches in France to issue Tesmoinages, so a Huguenot refugee was required to make a reconnaissance instead.

The entry in the register reads:

Misaubin, Jaques: 75 ans, et Jean, son fils: 28 ans, de Guienne.

Although the father was not described above as a Minister, he was subsequently named as such in a Bounty Pension list, and one of Huguenot clergymen.

It is possible that he assisted or officiated at one or more French churches in London but was not elected as a Minister at any particular church.

The younger Misaubin was naturalized in 1707.

Huguenot Cross – By Syryatsu – Own work (création personnelle) modified from File: Blason_ville_fr_Lacoste_(Vaucluse).svg by User:Spedona

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In the first half of the 18th century the area around St Martin’s Lane was a popular place for Huguenots to live.

Misaubin lived at number 96. One of his neighbours was Charles Angibaud, an apothecary, who had a good business in selling liquorice lozenges which he called Tranche des Blois.

Angibaud had been Louis XIV’s apothecary, but, as a Huguenot, he had left France in 1681.

He eventually became Master of the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries in 1728. It seems that John Misaubin was well integrated into the Huguenot community in London.

He is recorded as acting as a Temoins at the baptism of Marie Elizabeth La Coste on 18 July 1705, and Anne Blanchard on 7 December 1708 – both at the Church at Hungerford Market.

Misaubin went on to marry Charles Angibaud’s daughter, though by this time he seems to have been practising from Berwick Street.

The marriage was recorded as follows:

MISAUBIN 1709, 6 Jan. Le Sieur Jean Misobin, docteur en médecine, dem. in Berwick ANGIBAUD Street, par. S* James—Delle Marthe Angibaut, par. de St Martin in ye Filds; mar. par Mr de la Motte, min. de l’ég. de la Savoye., Licence 5 Jan. Téms. Jean Misaubin, Marthe Angibaud, C. Angibaud.

Misaubin passed the Royal College of Physician’s exams in physiology, pathology, and therapeutics at the first attempt in 1719.

He was admitted as a Licentiate of the college at a Comitia (AGM) held on 25 June 1719. Not bad for someone dismissed as a reputed quack.

At that time the Fellowship of the College was restricted to graduates of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Nevertheless, the Licentiate granted the holder the right to practise in, and within a seven-mile radius of, the City of London.

Until the 19th century there were usually fewer than sixty fellows at any one time and under one hundred licentiates (Licensed to practice and paying an annual fee).

One of Misaubin’s examiners was Dr Hugh Chamberlain of Huguenot descent, famous for guarding the secret of the obstetric forceps.

The physician’s profession could be a financially rewarding one.

At the top end of the scale the Royal Physician, Dr John Radcliffe, became wealthy enough to endow the Radcliffe Library at Oxford.

In 1713, Dr Hans Sloane purchased from Charles Cheyne the adjacent Manor of Chelsea, about 4 acres (1.6 ha), which he leased in 1722 to the Society of Apothecaries for £5 a year in perpetuity, requiring only that the Garden supply the Royal Society with 50 good herbarium samples per year, up to a total of 2,000 plants.

While Misaubin may not have been in their league, his income from pills and consultations ensured that he was well off.

He was able to afford Andien de Clermont, known for floral paintings in the Rococo style, to decorate his staircase.

The work was reputed to cost five hundred guineas, equivalent to approximately £123,000 in today’s currency.

Misaubin built a museum in his home at 96 St Martin’s Lane.

It is possibly depicted in an aquatint print by Hogarth, entitled In the Museum of the Quack Doctor or Marriage a la Mode, Plate 3 – The Inspection. 1743

In the museum of the quack doctor, the viscount Squanderfield holds out a small pill-box as a girl dabs her face with a handkerchief. Coloured aquatint after William Hogarth.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In the print Viscount Squanderfield is showing the doctor a pill box. The black patch on the Viscount’s neck is Hogarth’s way of revealing that the Viscount suffers from syphilis.

Perhaps he is asking for more medication for his ailment. The girl is distressed, probably because she has been infected by her master.

The woman in the red apron could be the doctor’s assistant. She holds what appears to be an open clasp knife, but it may be nothing more sinister than a thumb lancet used for bloodletting.

It has been suggested that the physician is Dr Richard Rock. He certainly has the stocky features of that doctor.

However, Rock was a German from Hamburg, and the printing on the open page on the stool is in French.

In translation it reads:

Explanation of two superb machines, the one for correcting dislocated shoulders, the other to extract corks, invented by the Monsr. of the pill. Seen and approved by the Royal Academy of Science in Paris.

This suggests that the physician was inspired by Misaubin’s reputation, even though he had been dead for almost a decade.

Another clue is the long wig on the head of the dummy in the cabinet, and to which the Viscount’s cane is pointing. This was the sort of wig worn by Misaubin.

The rest of the contents of the ‘museum’ are typical of what one would find in an 18th century collection of curiosities.

In 1719, the French painter Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), suffering from chronic tuberculosis, came to London to consult the famous physician Dr Richard Mead.

During his stay he mingled with the French community, and met Misaubin, probably in Old Slaughter’s Coffee House in St Martin’s Lane.

Watteau made a sketch of Misaubin on a paper napkin. This was later reproduced as an etching, in 1739, by the artist and picture dealer, Arthur Pond.

Watteau’s name probably assisted sales of the etching.

Misaubin is depicted as tall, with slender features and spindly legs.

The long swathe of black crepe attached to his hat indicates he is in mourning. A massive syringe is tucked under his left arm- more appropriate for treating an elephant than a human being.

The long wig is a style associated with Misaubin. He stands in a graveyard. A nearby sarcophagus has the traditional skull and crossbones carved at one, while a nearby, smaller, sarcophagus suggests the resting place of a child.

The caption Prenez des Pilules, Prenez des Pilules is reminiscent of the cry of a street hawker, the sale of the pills being one of the sources of Misaubin’s wealth.

He stands as a solitary figure in the graveyard, presiding over a scene of death, which contrasts strikingly with the physician’s oath to do no harm to the patient.

John Misaubin. Coloured soft-ground etching by A. Pond, 1739, after A. Watteau.

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Misaubin’s status, and comfortable life, is reflected in Joseph Goupy’s painting of Misaubin with his family.

He sits with confident ease at the centre of the painting, looking outwards to the viewer.

He is surrounded by his family, quill pen in his right hand, and giving a letter to his wife Marthe.

His father Jaques Misaubin is the clergyman holding a book in his right hand.

The young boy, John Edmund Misaubin, was educated at Clare College, Cambridge, but was tragically murdered at the age of twenty-three while returning home from Marylebone Gardens.

The well-stocked bookshelves, and Misaubin’s demeanour, convey a clear impression of a well- educated and scholarly gentleman, head of an upper-middling Georgian family.

Jean Misaubin and his family. Gouache painting by Joseph Goupy, 172-

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Detractors of Dr Misaubin would probably be surprised to learn that he was associated with the Rainbow Coffee HouseGroup that met at the coffee house in Lancaster Court, off St Martin’s Lane.

The members of this body were mainly Huguenot intellectuals who gathered to exchange books, correspondence and to engage in discussions about philosophical and theological topics associated particularly with Sceptism.

The philosophical doctrine that absolute knowledge is impossible, and enquiry must be a process of doubting to acquire approximate certainty.

The group had links with similar bodies in Paris and Holland and were part of an international network known as La Republique des Lettres, involved in the free exchange of ideas between Catholics, Protestants, and those with an interest in unorthodox views.

Misaubin gave advice to patients at the Rainbow Coffee House.

He would have also rubbed shoulders with Freemasons because there was a Masonic Lodge at the coffee house, with a thriving membership of sixty-three in 1730.

The Lodge was first mentioned in the Grand Lodge Minutes of 28 August 1730 and appears in the list of Lodges on 17 March 1731.

The Masonic martyr, John Coustos, was also a member, and the celebrated Freemason, Dr John Theophilus Desaguliers, was a habitué of the Rainbow Coffee House.

John Coustos

IMAGE LINKED: Wellcome Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Misaubin had some very influential friends. He requested the Dukes of Richmond and Montagu, as well as Lord Baltimore, to be the executors of his will.

All three were important Freemasons. John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu, became the first aristocratic Grand Master of Grand Lodge in 1721, and Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond, was a grandson of Charles II. He was Master of the Horn Lodge when Misaubin was initiated in 1730.

Charles Calvert, 5th Lord Baltimore, was a member of the family who were the proprietors of the colony of Maryland.

Charles was also a patron of Andien de Clermont who had painted Misaubin’s staircase.

He was also friendly with Thomas Hill, an early tutor and member of the Duke of Richmond’s household, a Fellow of the Royal Society, and sometime Secretary of the Board of Trade.

Hill wrote to the Duke of Richmond on 17 November to recount a meeting with Misaubin, whom he describes as looking yellower and greener and blewer than usual…and besides his legs swel much at the ankles.

However, Hill added that he was impressed with the quality of Misaubin’s wine. Hill wrote again to the Duke in February 1733 about another dinner hosted by Misaubin whom he refers to affectionately as Mizzy.

Apparently Misaubin consumed so much wine that he was drunk. In the Mock Doctor, Fielding wrote that Misaubin treated his friends and patients to more wine than they paid him for their treatment.

Yellowing of the skin and swollen ankles are symptoms of advanced cirrhosis of the liver.

Given the social circles in which Misaubin mixed, it is no wonder that he gravitated towards Freemasonry, albeit towards the end of his life.

A notice in the London Evening Post of 17 March announced that there had been a meeting of the Horn Lodge in Palace Yard, Westminster the previous Monday night.

The Horn Lodge (now the Royal Somerset House and Inverness Lodge No. 4) had originally met at the Rummer and Grapes Tavern, in Channel Row, Westminster.

It was the most influential of the four London Lodges that came together to form the Premier grand Lodge in 1717.

Its aristocratic membership had included four grandsons of Charles II, and James (later Earl) Waldegrave, grandson of James II.

There had also been a significant number of military officers, some of whom played an active part in the work of the Lodge.

Colonel Inwood was Master of the Lodge in 1723, with Colonel Purcell as his Senior Warden.

In 1725 Colonel Houghton became Master of the Lodge with Major Godolphin as his Senior Warden.

Some of the members were successful merchants like George Heathcote who had business interests in the West Indies and was reckoned to be one of the wealthiest commoners in Britain.

There was a smattering of scientifically gifted members such as the horologist and scientific instrument maker George Graham.

In 1720 about twenty members were Fellows of the Royal Society. A similar number sat as magistrates, some as chairman of the bench.

Almost a third were members of Parliament. Some were senior government officials, like Charles Delafaye.

The overriding characteristics of the membership of the Lodge at the Rummer and Grapes were wealth, power, and influence.

Hogarth’s Night (c.1860)

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The Rummer and Grapes Tavern as depicted in Hogarth’s Night (c.1860) The drunk receiving the contents of a bucket is wearing a masonic master’s jewel, and his servant’s sword indicates a tyler.

The man with the mop may be an allusion to the Tyler erasing chalk marks from the lodge floor.

The Rummer and Grapes on the inn sign depict one of the four lodges which founded Grand Lodge.

Misaubin was accompanied by an elite group of individuals on his initiation.

The Duke of Richmond officiated as the Master. The list of initiates could have been drawn from the pages of The Tatler magazine (founded by Sir Richard Steele in 1709). It included:

The Marquis of Beaumont, eldest son, and heir apparent to his Grace the Duke of Roxburghe

Earl Kerr of Wakefield

Sir Francis Henry Drake Bart

The Marquis De Quesne

Thomas Powell of Nanteos, Esq.

The Chevalier Ramsay

Dr Misaubin

Misaubin was reported as being present at the Consecration of a new lodge in Highgate.

This could well have been Lodge No. 79, which received its Warrant on 27 June 1731, and met at The Castle, High Street, Highgate, London.

It was later incorporated with a Lodge held at The Swan, Hampstead, and Misaubin was thought to have been its Master, perhaps on the occasion of a visit.

Misaubin was elevated, albeit temporarily, to high office when he acted as Junior Grand Warden pro tempore at the Quarterly Communication of Grand Lodge held at The Devil Tavern within Temple Bar on 2 March 1732.

He was also selected as a Grand Lodge Steward for 1733, at a meeting of Grand Lodge on 19 April 1732.

Dr John Misaubin died on 20 April 1734. A death notice in the Gentleman’s Magazine referred to him as an eminent physician.

He was well appreciated by his friends and Brother Freemasons despite being ridiculed by Hogarth and Fielding.

Unfortunately, these have been the impressions that filtered down to later generations. His will was written on 6 April 1734, shortly before he died.

It shows that he was not even-handed in the provision for members of his family. His wife was awarded a shilling, and his best French Bible, on the grounds that provision had already been made for her maintenance in the marriage contract.

The whole of his estate, including ready money and that owed to him, diamonds, jewels, watches, plate, pictures, household furniture, coaches, chariots, horses, goods, and chattels he left to his son Edmund.

No mention of a personal memento for his wife.

If Edmund died unmarried before he was twenty-one, then the bequest would pass to the Huguenot hospital, La Providence, near Hoxton.

He stipulated that none of the bequest should pass to his wife, or her relations, the Angibaud family.

Furthermore, if Edmund should die young, as he did, being murdered, all his nostrums and recipes for the cure of distemper and maladies should be published for the benefit of the public.

Edmund was made the sole executor of the will with, as previously mentioned, the supervision of the Dukes of Richmond and Montagu, and Lord Baltimore.

He asked each to accept a ring valued at twenty shillings (about sixty pounds in today’s money).

His two friends, John Fouvive and Samuel Baldwyn, were asked to act as joint supervisors and overseers.

However, Misaubin’s wishes were overturned when his wife was granted the power of sole executor of her husband’s will.

Why Dr Misaubin would have framed his will in the way that he did is something of mystery.

He did not leave much written material, but perhaps there is a document somewhere that might provide an explanation.

A large table in a lecture hall with many commercial medicine vendors and practitioners seated around it: in the background are many tiers of spectators. Engraving, 1748

IMAGE LINKED: wikimedia Collection Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

In an advert in the Daily Advertiser for April 1743, Charles Angibaud Jr. announced that he had forsaken pharmacy for medicine, but he still intended to sell his father’s famous Pectoral Lozenges of Blois from the house of his aunt, the widow of Dr Misaubin, in St Martin’s Lane.

Misaubin achieved post-mortem recognition by being listed in the Pharmacopoeia Empirica for 1748.

His wife probably continued selling his pills, because her will of 28 September 1749, records that she wishes to leave her secret of the Venereal Pill to her nephew Charles Angibaud.

Given the number of cures advertised in the pages of contemporary newspapers and magazines, perhaps some caution should be exercised before pillorying Dr Misaubin for quackery.

Article by: Nigel Wade

Educated at The Stationers’ Company's School, and the University of London.

A regular writer for the school magazine and ‘The Old Stationer’; member of the Brentwood Writers’ Circle.

Nigel has written one children's book ‘City Fox’, and various articles for ‘The Square Magazine’.

Quacks – Fakers & Charlatans in Medicine

By: Roy Porter

If the thought of visiting the doctor or having a spell in the hospital gives most people pause to contemplate their mortality, then such thoughts must pale when compared to the experiences of our ancestors.

They were largely at the mercy of a medical fraternity renowned more for the eccentricity of their cures than their efficacy.

From the pisse prophets who would gaze upon a patient’s urine to establish the most accurate diagnosis, to the pushers of such remedies as “Walkers Jesuit Drops” to cure venereal disease, Quacks is a thrilling history of opportunists, charlatans, conmen, some deludedly sincere doctors, and—ultimately—of our own enduring credulity.

William Hogarth: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings

By: Elizabeth Einberg

William Hogarth (1697–1764) was among the first British-born artists to rise to international recognition and acclaim and to this day he is considered one of the country’s most celebrated and innovative masters.

His output encompassed engravings, paintings, prints, and editorial cartoons that presaged western sequential art. This comprehensive catalogue of his paintings brings together over twenty years of scholarly research and expertise on the artist, and serves to highlight the remarkable diversity of his accomplishments in this medium.

Portraits, history paintings, theater pictures, and genre pieces are lavishly reproduced alongside detailed entries on each painting, including much previously unpublished material relating to his oeuvre.

This deeply informed publication affirms Hogarth’s legacy and testifies to the artist’s enduring reputation.

Engravings by Hogarth

By: William Hogarth

This book contains 101 of Hogarth’s finest and most important engravings, including all the major series or “progresses”: “The South Sea Scheme,” A Harlot’s Progress, “A Midnight Modern Conversation,” A Rake’s Progress, Before and After, Marriage à la Mode, Industry and Idleness, “The March to Finchley,”The Four Stages of Cruelty, “Time Smoking a Picture,” “Tailpiece,” and many more, including ten study sketches and paintings that show how the final works evolved.

Sean Shesgreen, a foremost authority on Hogarth, has consistently selected the best states of the plates to be used in this edition and has carefully introduced them, commenting upon the artist’s milieu and the importance of plot, character, time, setting, and other dimensions.

A most important aspect of this book, found in no other Hogarth edition, is the positioning of the editor’s commentary on each plate on a facing page.

With the incredible and sometimes overwhelming amount of detail and action going on in these engravings, this is a most helpful feature.

Recent Articles: in people series

Celebrate the extraordinary legacy of The Marquis de La Fayette with C.F. William Maurer's insightful exploration of Lafayette's 1824-25 tour of America. Discover how this revered leader and Freemason was honored by a young nation eager to showcase its growth and pay tribute to a hero of the American Revolution. |

Albert Mackey and the Civil War In the midst of the Civil War's darkness, Dr. Albert G. Mackey, a devoted Freemason, shone a light of brotherhood and peace. Despite the nation's divide, Mackey tirelessly advocated for unity and compassion, embodying Freemasonry's highest ideals—fraternal love and mutual aid. His actions remind us that even in dire times, humanity's best qualities can prevail. |

Discover the enduring bond of brotherhood at Lodge Dumfries Kilwinning No. 53, Scotland's oldest Masonic lodge with rich historical roots and cultural ties to poet Robert Burns. Experience rituals steeped in tradition, fostering unity and shared values, proving Freemasonry's timeless relevance in bridging cultural and global divides. Embrace the spirit of universal fraternity. |

Discover the profound connections between John Ruskin's architectural philosophies and Freemasonry's symbolic principles. Delve into a world where craftsmanship, morality, and beauty intertwine, revealing timeless values that transcend individual ideas. Explore how these parallels enrich our understanding of cultural history, urging us to appreciate the deep impacts of architectural symbolism on society’s moral fabric. |

Discover the incredible tale of the Taxil Hoax: a stunning testament to human gullibility. Unmasked by its mastermind, Leo Taxil, this elaborate scheme shook the world by fusing Freemasonry with diabolical plots, all crafted from lies. Dive into a story of deception that highlights our capacity for belief and the astonishing extents of our credulity. A reminder – question everything. |

Dive into the extraordinary legacy of Alexander Von Humboldt, an intrepid explorer who defied boundaries to quench his insatiable thirst for knowledge. Embarking on a perilous five-year journey, Humboldt unveiled the Earth’s secrets, laying the foundation for modern conservationism. Discover his timeless impact on science and the spirit of exploration. |

Voltaire - Freethinker and Freemason Discover the intriguing connection between the Enlightenment genius, Voltaire, and his association with Freemasonry in his final days. Unveil how his initiation into this secretive organization aligned with his lifelong pursuit of knowledge, civil liberties, and societal progress. Explore a captivating facet of Voltaire's remarkable legacy. |

Robert Burns; But not as we know him A controversial subject but one that needs addressing. Robert Burns has not only been tarred with the presentism brush of being associated with slavery, but more scaldingly accused of being a rapist - a 'Weinstein sex pest' of his age. |

Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse Discover the captivating story of Richard Parsons, 1st Earl of Rosse, the First Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Ireland, as we explore his rise to nobility, scandalous affiliations, and lasting legacy in 18th-century Irish history. Uncover the hidden secrets of this influential figure and delve into his intriguing associations and personal life. |

James Gibbs St. Mary-Le-Strand Church Ricky Pound examines the mysterious carvings etched into the wall at St Mary-Le-Strand Church in the heart of London - are they just stonemasons' marks or a Freemason’s legacy? |

Freemasonry and the Royal Family In the annals of British history, Freemasonry occupies a distinctive place. This centuries-old society, cloaked in symbolism and known for its masonic rituals, has intertwined with the British Royal Family in fascinating ways. The relationship between Freemasonry and the Royal Family is as complex as it is enduring, a melding of tradition, power, and mystery that continues to captivate the public imagination. |

A Man Of High Ideals: Kenneth Wilson MA A biography of Kenneth Wilson, his life at Wellington College, and freemasonry in New Zealand by W. Bro Geoff Davies PGD and Rhys Davies |

In 1786, intending to emigrate to Jamaica, Robert Burns wrote one of his finest poetical pieces – a poignant Farewell to Freemasonry that he wrote for his Brethren of St. James's Lodge, Tarbolton. |

Alex Lishanin explores Mumbai and discovers the story of Lodge Rising Star of Western India and Manockjee Cursetjee – the first Indian to enter the Masonic Brotherhood of India. |

Aleister Crowley - a very irregular Freemason Aleister Crowley, although made a Freemason in France, held a desire to be recognised as a 'regular' Freemason within the jurisdiction of UGLE – a goal that was never achieved. |

Sir Joseph Banks – The botanical Freemason Banks was also the first Freemason to set foot in Australia, who was at the time, on a combined Royal Navy & Royal Society scientific expedition to the South Pacific Ocean on HMS Endeavour led by Captain James Cook. |

Making a Mason in Prison: the John Wilkes’ exception? |

"To be a good man and true" is the first great lesson a man should learn, and over 40 years of being just that in example, Dr Buck won the right to lay down the precept. |

Elias Ashmole: Masonic Hero or Scheming Chancer? The debate is on! Two eminent Masonic scholars go head to head: Yasha Beresiner proposes that Elias Ashmole was 'a Masonic hero', whereas Robert Lomas posits that Ashmole was a 'scheming chancer'. |

Sir Arthur Sullivan - A Masonic Composer We are all familiar with the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, but did you know Sullivan was a Freemason, lets find out more…. |

The Much-Maligned Dr John Misaubin The reputation of the Huguenot Freemason, has been buffeted by waves of criticism for the best part of three hundred years. |

Was William Morgan really murdered by Masons in 1826? And what was the lie Masonic author Rob Morris told? Find out more in the intriguing story of 'The Morgan Affair'. |

Lived Respected - Died Regretted Lived Respected - Died Regretted: a tribute to HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh |

Who was Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a Freemason, American Civil War Soldier, renowned sculptor ? |

A Masonic author and Provincial Grand Master of Forfarshire in Scotland |

Who was Philip, Duke of Wharton and was he Freemasonry’s Loose Cannon Ball ? |

Richard Carlile - The Manual of Freemasonry Will the real author behind The Manual of Freemasonry please stand up! |

Nicholas Hawksmoor – the ‘Devil’s Architect’ Nicholas Hawksmoor was one of the 18th century’s most prolific architects |

By Bro. Anthony Oneal Haye (1838-1877), Past Poet Laureate, Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, Edinburgh. |

The Curious Case of the Chevalier d’Éon A cross-dressing author, diplomat, soldier and spy, the Le Chevalier D'Éon, a man who passed as a woman, became a legend in his own lifetime. |

Mozart Freemasonry and The Magic Flute. Rev'd Dr Peter Mullen provides a historical view on the interesting topics |

masonic knowledge

to be a better citizen of the world

share the square with two brothers

click image to open email app on mobile device